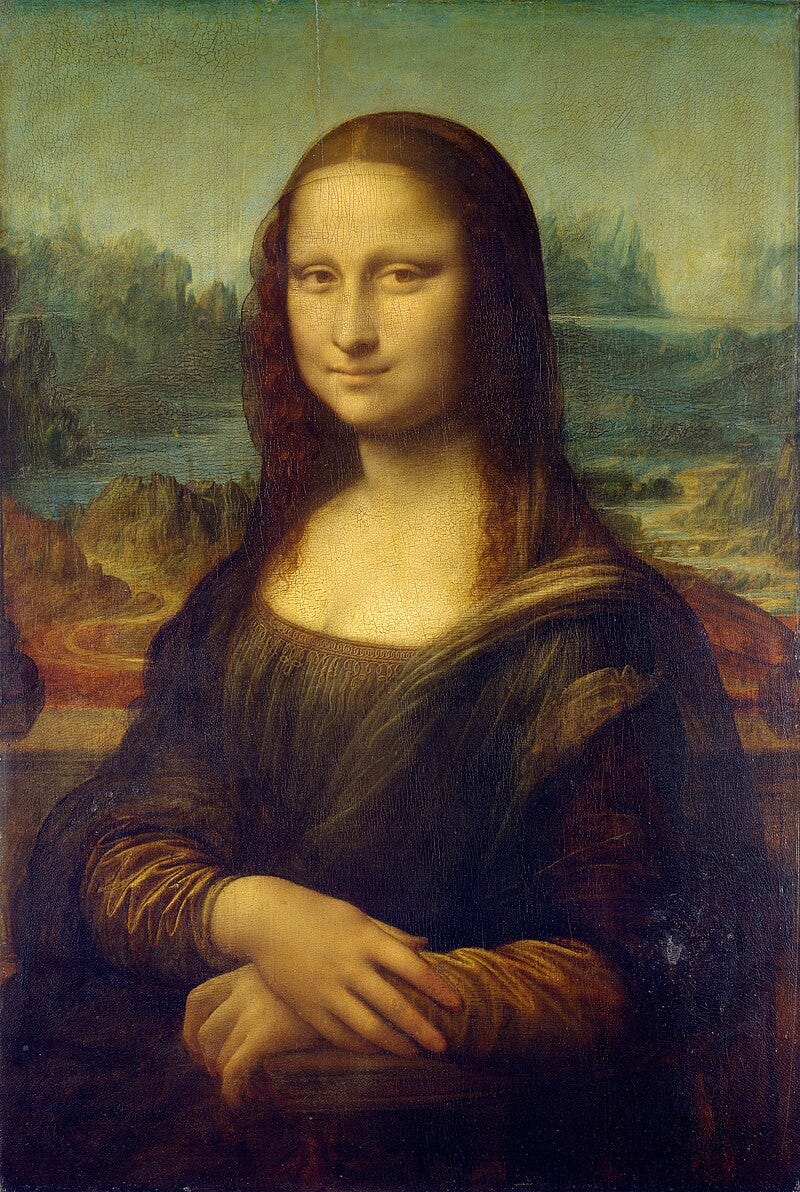

Art survives not because it is hung on walls, but because it continues to speak across centuries. The true masterpieces are not just beautiful, they are alive with secrets, revisions, and scars that only time could reveal. The Mona Lisa is not one painting, it is several. Buried beneath the surface, infrared scans have uncovered earlier versions where Leonardo shifted her veil, repositioned her hands, even drafted a different background. What the world sees in the Louvre is not a single vision but a lifetime of revisions.

This is why the Collector’s Edition matters. Masterpieces endure not because they are frozen, but because they are restless, layered, and alive. Each of the 20 works here carries more than paint on canvas, it holds survival stories, hidden revisions, and human drama. To start with Leonardo’s obsession is to set the tone: nothing here is static, and every masterpiece is more than it seems.

From there, we move to van Eyck, Grünewald, David, Botticelli, and onward. Five for everyone, fifteen reserved for Founders. Each one adds to the same truth: beauty refuses to die, no matter what history throws at it.

1. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa

Her smile has become cliché, but the true wonder is hidden in layers invisible to the naked eye. Infrared reflectography reveals da Vinci’s uncertainty. Hands adjusted, veil redrawn, shadows softened, rethought, and softened again. Leonardo kept painting as though chasing perfection he knew he would never catch.

Even her history carries scars. Stolen from the Louvre in 1911, it became more famous because of its absence than its presence. By the time it returned two years later, the portrait had turned into a global icon. What makes it a masterpiece is not just the face; it’s the mystery that grows every time technology or history strips away another layer.

2. Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait

At first glance, Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife stand politely in a room. But the dog at their feet, the single lit candle above, the cast-off shoes, all speak in symbols. Fidelity, divine witness, and sacred space are embedded in what looks like bourgeois life. The convex mirror at the back wall reflects two additional figures, likely van Eyck and a witness, turning a domestic scene into a legal declaration.

Infrared analysis has shown van Eyck reconsidered elements — details painted, scraped, and repainted. Nothing is accidental. The portrait is both contract and confession, a coded document in paint. To modern eyes, it’s a puzzle; to contemporaries, it was a binding truth. That duality is why it continues to unsettle viewers today.

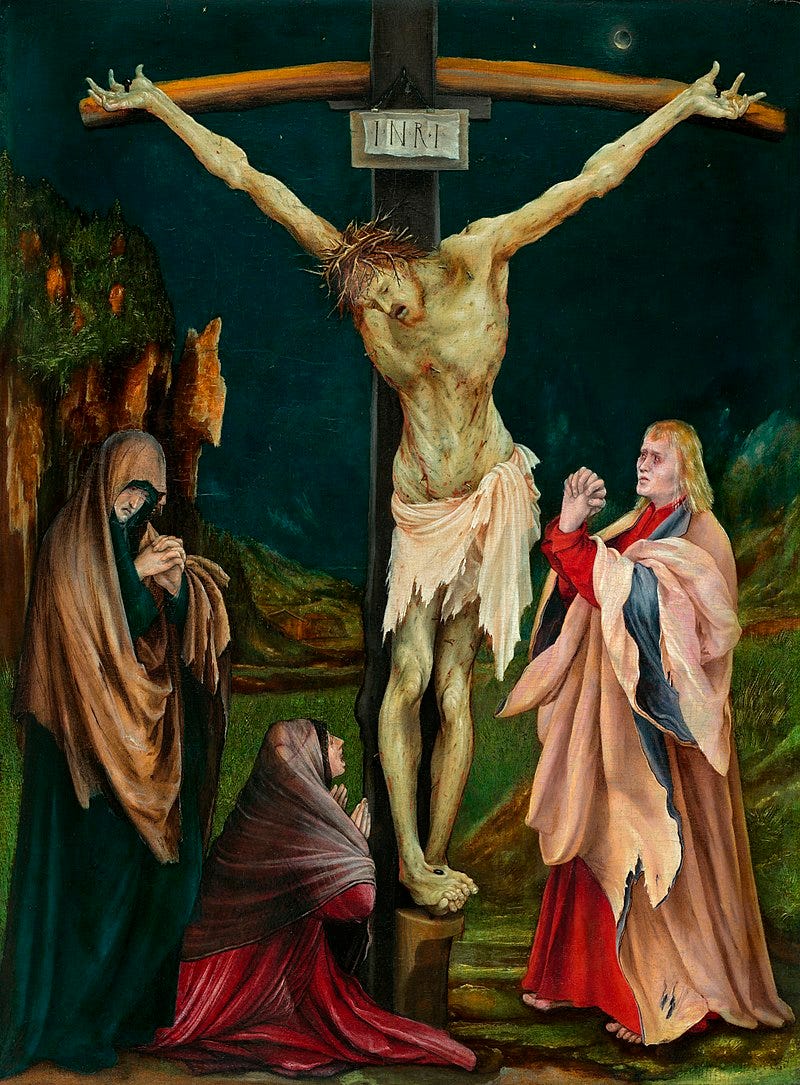

3. Matthias Grünewald’s Crucifixion

Grünewald’s Crucifixion is not the serene Christ of Raphael or Perugino. His Christ writhes, skin torn and twisted, the nails grotesquely oversized. When the Kress Foundation acquired it in 1952 for $260,000, it was considered a daring choice. Rush Kress himself was unconvinced, but his advisors insisted.

This was no genteel devotional panel; it was a spiritual horror meant to confront disease and suffering head-on. For plague-ridden Germany, it was a mirror of agony. For mid-20th-century collectors, it was a reminder that beauty is not always consoling. Its preservation in Washington today is a testament to courage, both the painter’s and the collector’s.

4. Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon in His Study

David’s 1812 portrait of Napoleon is theater disguised as realism. The candles burn low, the clock reads past 4 a.m., his uniform rumpled. Napoleon is shown not commanding armies, but drafting laws, exhausted from the weight of empire.

The painting was made for a Scottish nobleman who idolized Napoleon. Yet beneath the propaganda lies fatigue, almost guilt. By the time the Kress Foundation acquired it in 1954, Napoleon was long gone, but the painting carried the contradictions of power: splendor masking collapse. Its survival is a reminder that art often preserves not what rulers intended, but what they tried to hide.

5. Sandro Botticelli’s Giuliano de’ Medici

This portrait, purchased for $365,000 in 1949, carries with it a story darker than its subject. It had belonged to Count Vittorio Cini, who was sent to Dachau during the Nazi occupation. His son Giorgio ransomed him with gold, funds partly raised through selling family treasures, including this Botticelli.

The painting is more than Florentine elegance; it is a ledger of human cost. To see Giuliano’s calm face is to remember a desperate son who gave up beauty to save his father. Few masterpieces embody so directly the exchange between survival and art.

You’ve just seen the first 5. The next 15 masterpieces from Leonardo, Titian, Velázquez, van Gogh, Rubens, Fra Angelico, Michelangelo, Picasso, and more are reserved for Founders subscribers only.

Upgrade to Founder’s Edition to unlock the full Collector’s list, with all 20 masterpieces and their hidden stories.