Art, the Nude, and the Sacred

What Western Painting Reveals About the Soul

You can tell what a civilization worships by what it dares to undress.

Most societies, across time, have feared the nude. They covered it, punished it, or reduced it to desire. But in the Western tradition, from ancient Greece to the academies of 19th-century France, the human body wasn’t just flesh, it was revelation. The nude was never merely erotic. It was philosophical. Sacred. It dared to speak of truth, soul, virtue, and even the divine.

To understand this, you have to go back, not to the 20th century or the Renaissance, but to a limestone boy carved in Athens over 2,500 years ago. The Kritios Boy, with his relaxed hips and lifelike posture, wasn't just a statue. He was a statement. A human body rendered so mathematically perfect that it suggested something bigger than man. The Greeks weren’t just sculpting bodies. They were sculpting ideals.

They called this ideal kalokagathia, the unity of the beautiful and the good. A harmony between the body and the soul. For them, a well-formed body was attractive and morally superior. The body revealed the soul.

That’s why they portrayed their gods as nude. Apollo, Hermes, even heroic mortals, always nude, always composed. Their enemies, by contrast, wore armor or foreign robes. The barbarian was clothed. The Greek was bare. Nakedness was nobility.

But here's where it gets more fascinating. The Greeks didn’t just stop at athletic nudity. They turned the human form into a geometrical problem. Think of Polykleitos’ Canon, a treatise that defined ideal bodily proportions using ratios. Or Vitruvius’ square-and-circle man, later drawn by Leonardo. The body wasn’t random. It mirrored the cosmos.

This idea exploded again during the Renaissance.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Michelangelo’s David. You’ve seen him—17 feet tall, tense, coiled with potential. But forget the size for a moment. What Michelangelo did was give a biblical shepherd the body of a god. His David isn’t a boy. He’s a vessel of moral force, a fusion of Hebrew scripture and Greek perfection.

And he’s completely nude.

That choice was not casual. Michelangelo wasn’t aiming for eroticism. His David was a civic guardian. A visual manifesto of Florence’s republican ideals. A political figure carved in classical flesh.

And still, you can feel the weight of divinity in his marble veins.

But to get to David, Western art had to pass through centuries of silence.

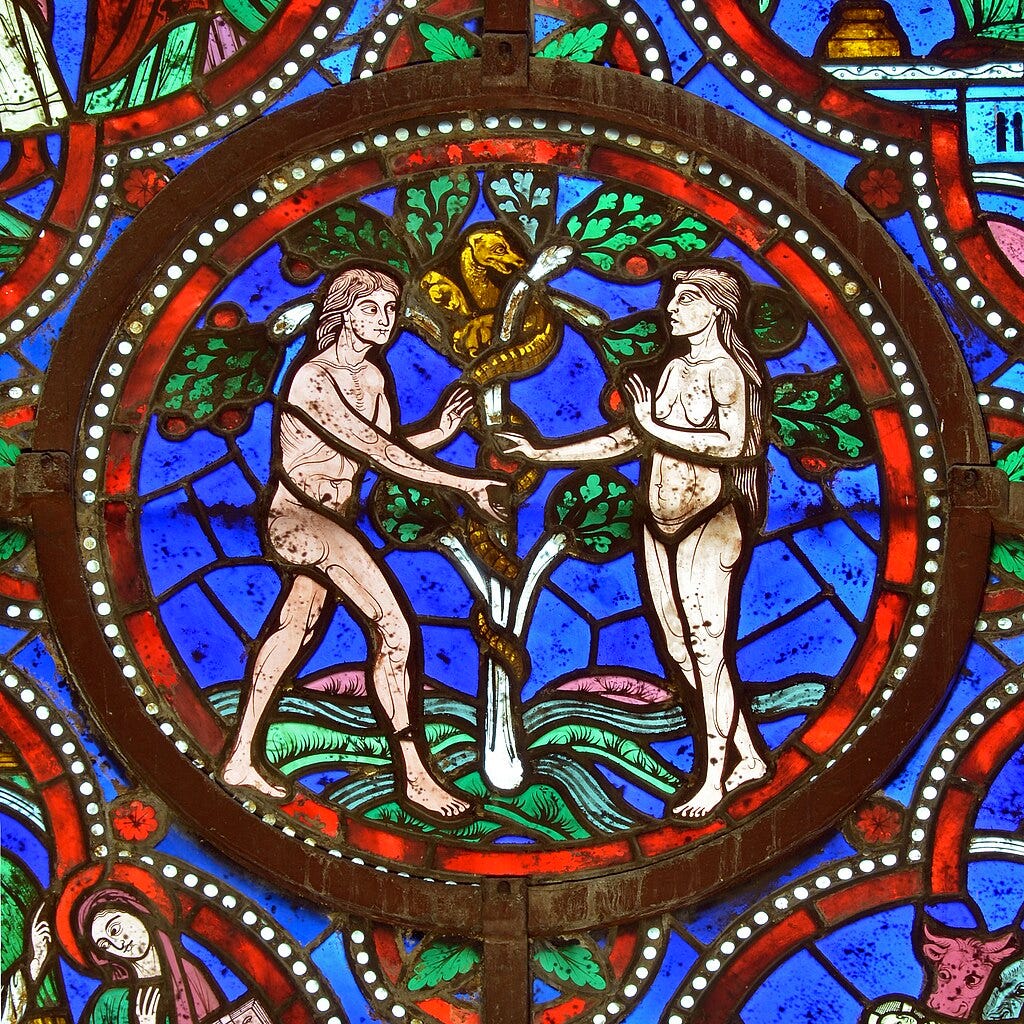

When Christianity took over the Roman world, the nude all but disappeared. The body became suspect. The flesh was the seat of temptation. Images of nakedness were mostly confined to hellscapes or reminders of shame—like Adam and Eve covering themselves after the Fall.

For nearly a thousand years, the sacred was draped.

Until Giotto.

In his Last Judgment, painted in Padua in the early 1300s, Giotto painted nude bodies not to glorify them—but to warn. Still, something had shifted. The forms had weight. They moved. They expressed pain and urgency. The sacred and the physical were merging again.

But it took the Renaissance to fully restore the nude to its high place. And it wasn’t the male body that led this time—but the female.

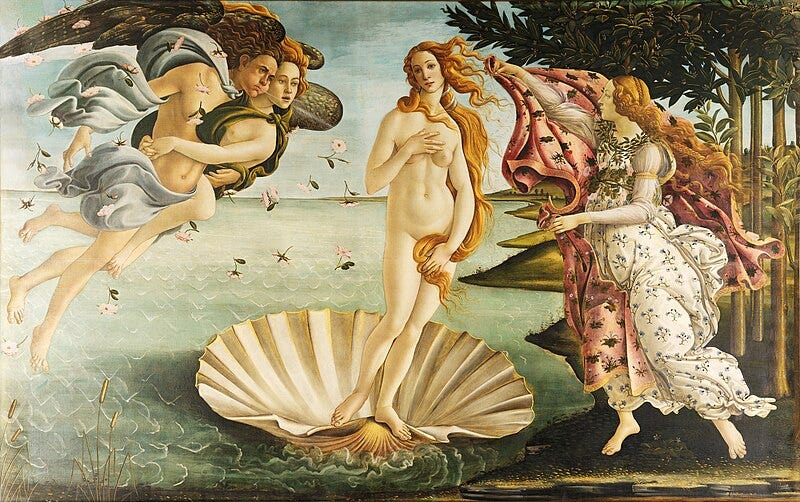

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus changed everything. There she stood on a seashell, emerging from the foam, covering herself modestly, yet with theatrical poise. Inspired by classical statuary, Botticelli’s Venus wasn’t a woman. She was an idea—divine love, beauty, and celestial truth made flesh.

She wasn’t to be possessed. She was to be contemplated.

In fact, Renaissance artists viewed Venus as twofold: Venus Naturalis, representing earthly beauty and fertility, and Venus Coelestis, representing divine love. A naked body could now point beyond itself.

This duality shaped art for centuries.

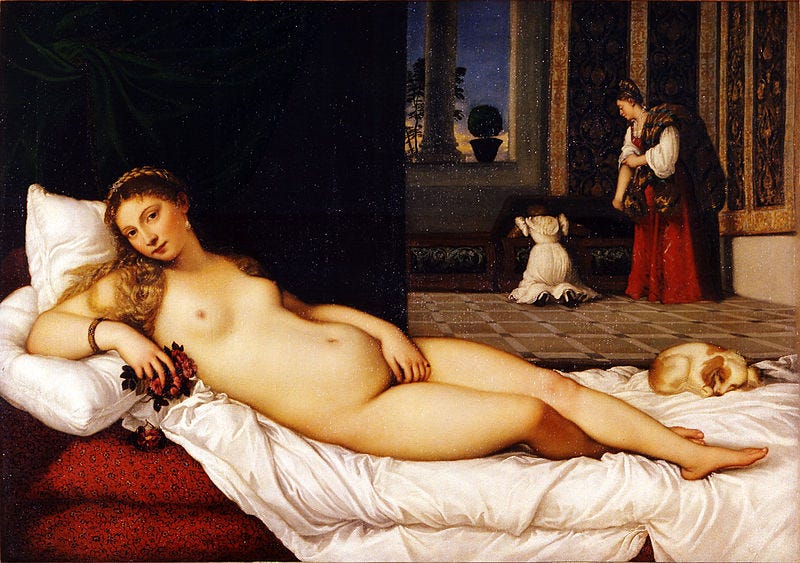

Titian’s Venus of Urbino refined this further. His reclining nude, looking directly at the viewer, is neither shy nor seductive. She’s poised. A visual echo of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, her curves rhyme with the landscape behind her. It’s a painting about harmony, not lust. She is asleep. We are the ones awakened.

Yet this new openness toward nudity came with a cost.

The female nude became increasingly passive. Male artists portrayed women as muses, as goddesses, but often through the lens of the male gaze. John Berger later wrote that “men act, women appear.” Women became images—mirrors for male ideals.

Still, within that imbalance, there was room for transcendence.

Look at Bouguereau.

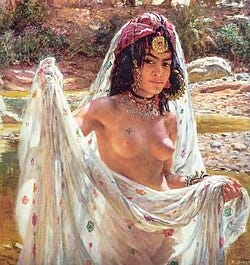

In works like The Birth of Venus or Nymphs and Satyr, Bouguereau’s bodies are impossibly smooth, soft, glowing with light. They are sensual—but also mythic. He painted women not just as sexual beings, but as emblems of innocence, fertility, and divine play.

His technique was so precise, so reverent, that critics accused him of being too polished. But that’s exactly the point. Bouguereau wasn’t painting real women. He was painting metaphysical ideals.

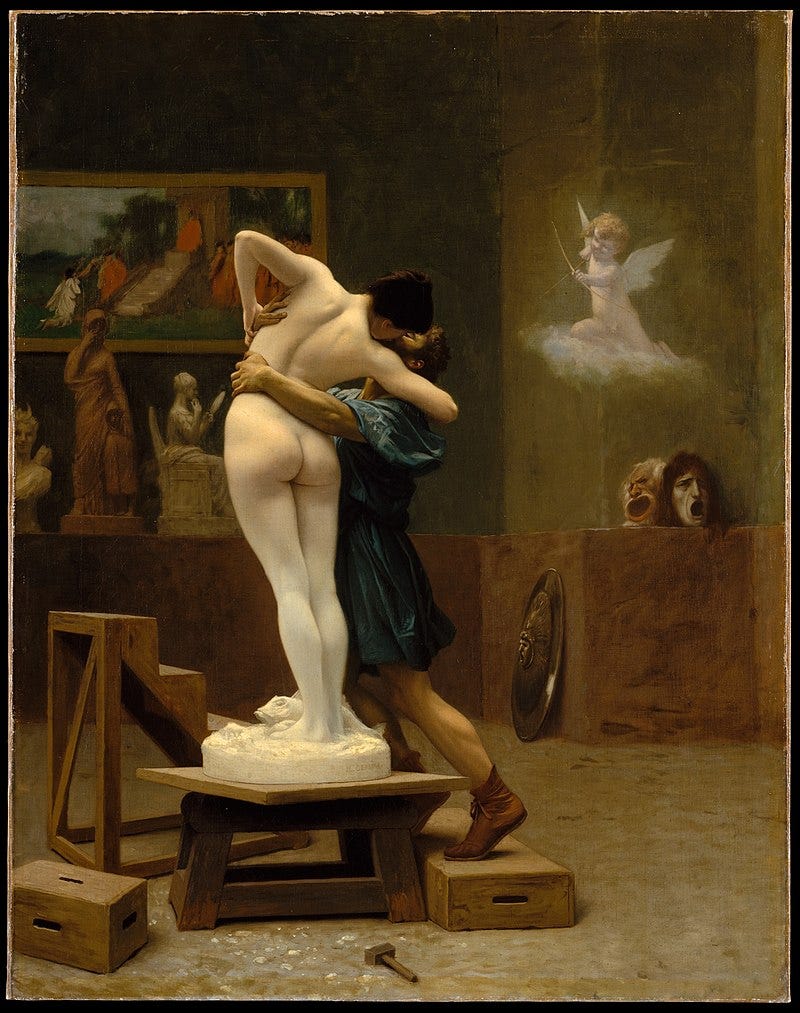

There’s one more name worth mentioning—William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s near-contemporary and rival: Jean-Léon Gérôme. His Pygmalion and Galatea is a visual metaphor for the artist’s own longing. The statue he sculpts comes to life, not because of lust, but because of love. The nude, here, is animation. Soul entering form.

This links back to Plato’s old idea that beauty awakens the soul to truth.

And truth, in this tradition, was often clothed in skin.

This is what separates the Western nude from mere eroticism. The Greeks didn’t sculpt bodies for arousal. They sculpted ideals. Renaissance artists didn’t paint flesh to titillate. They painted virtue, harmony, and divine geometry.

Even in the 19th century, when Academic art was criticized for being too pretty, the best artists still saw the nude as a moral canvas.

And what about today?

Some argue the nude has lost its sacred aura that digital pornography, advertising, and mass media have hollowed it out. That what was once a gateway to the divine has become a scrollable commodity.

But maybe that’s why looking back matters.

Because in the West’s greatest paintings, the nude wasn’t vulgar. It was philosophical. It stood for everything we once believed the soul could be. Noble, radiant, proportioned, true.

And if art still has power today, it’s because those bodies, chiseled in marble, painted in oil, dreamed in color, still ask us a simple, eternal question:

What is beauty, if not the truth made visible?

Excellent writing 👍🏼

I know almost nothing about art but love reading your articles and learning!

I found it very interesting how you explain that the nude in art was not just something erotic, but a way to show ideals, beauty, and even the divine. But I wonder: do you think that today the nude can still be used in art with that deeper meaning, or is it already too marked by the commercial and the superficial?