Beauty Didn’t Vanish — We Buried It

When Art Stopped Lifting Us

“Art moves us because it is beautiful, and it is beautiful in part because it means something. It can be meaningful without being beautiful; but to be beautiful it must be meaningful.” - Robert Scruton

Of all the words humanity has buried, none has been more quietly abandoned than “beauty.” For centuries, beauty was treated as a truth in itself, a value as real as justice or love. Then, almost without warning, beauty lost all meaning entirely. Beauty, in the modern parlance, has been decoupled from truth. It isn’t what you know innately but merely a descriptive word for whatever we feel like.

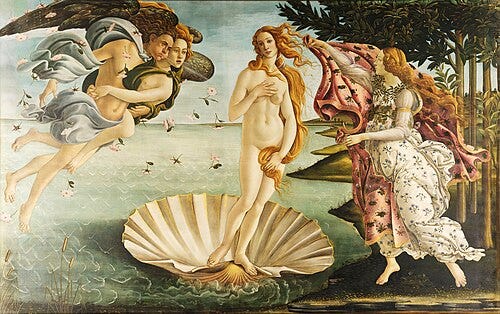

For centuries, if you asked a poet, painter, or composer what their work was for, the answer was simple: to reveal beauty. From the Enlightenment to the Romantics, beauty was understood as something transcendent. It gave form to moral and spiritual truths. It was a necessity. It gave meaning to what otherwise would have been noise.

Why Beauty Matters by Robert ScrutonThat conviction began to fracture in the aftermath of modernism. Artists stopped seeing beauty as their duty. Originality and transgression became the focus. Suddenly, to disturb and shock was seen as more profound than to elevate or heal. Ugliness was a statement.

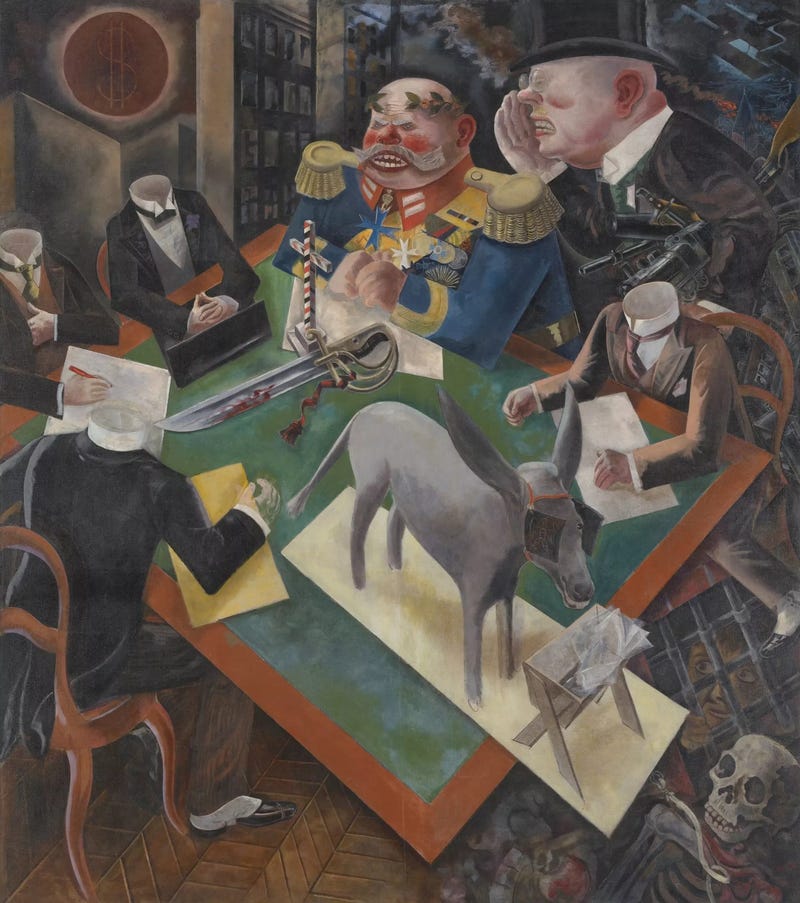

Critics like Clement Greenberg declared that beauty was unserious. Expression was what mattered. The artist became a rebel, defined against ordinary moral life. This was more than a stylistic change. It redefined art’s purpose. The new aesthetic was born in places like interwar Germany. The canvases of George Grosz, the operas of Alban Berg, and the novels of Heinrich Mann no longer spoke of harmony or hope. They glorified chaos. In France, the writings of Georges Bataille and Jean Genet pushed this even further. Beauty was framed not as a higher aim, but as something naive, even dishonest.

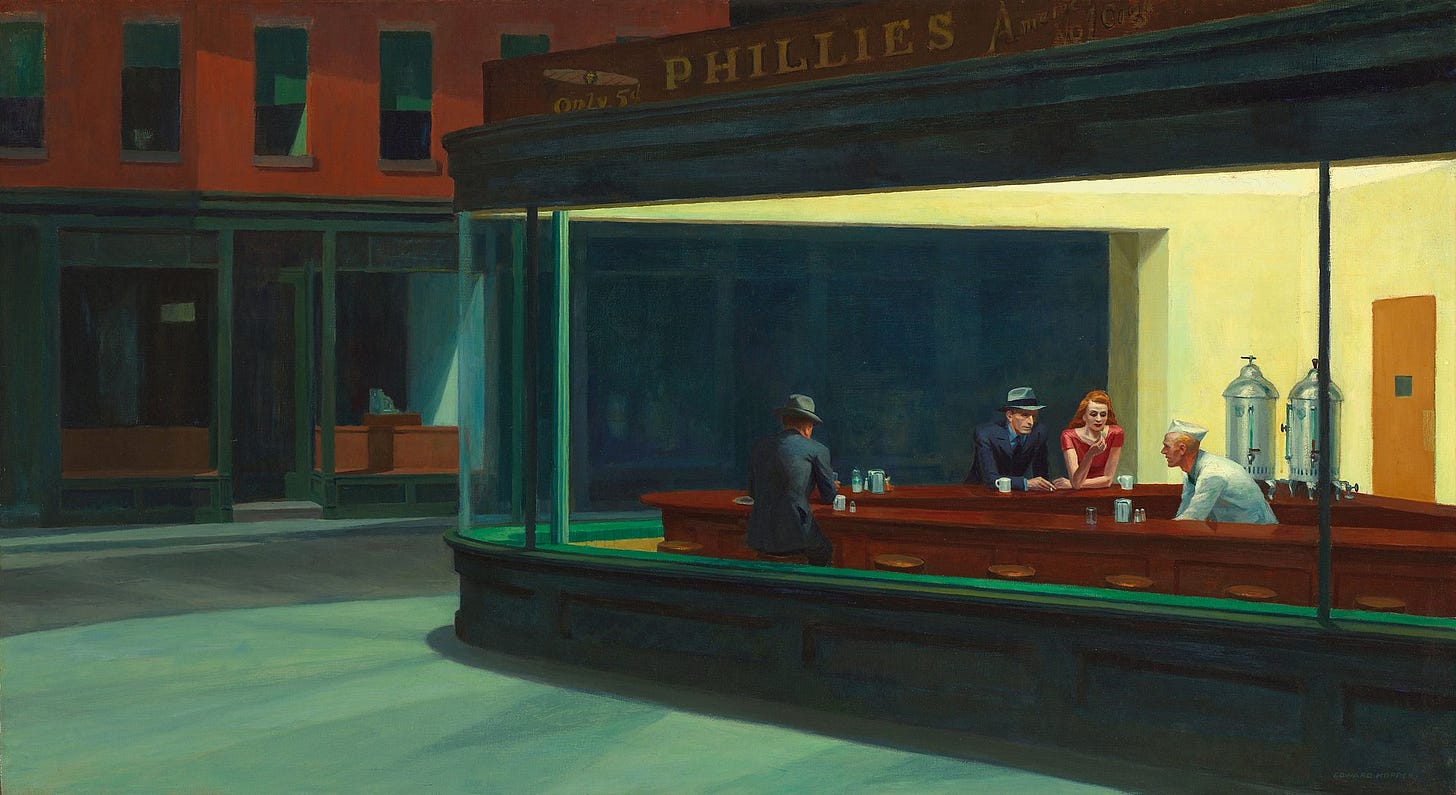

There were artists who fought back. T. S. Eliot tried to reassemble meaning from the ruins. Edward Hopper painted the quiet dignity of ordinary life. Samuel Barber and Wallace Stevens treated beauty as sacred. But slowly, they were pushed to the side. What once signified failure — immorality, disruption — was now hailed as artistic courage.

One of the clearest examples of this shift came in opera. Modern directors took masterpieces and smothered their beauty in vulgarity. In 2004, the Catalan director Calixto Bieito staged Die Entführung aus dem Serail not as Mozart wrote it, a story of mercy, love, and faithfulness, but in a Berlin brothel. Tender arias were drowned in scenes of sex, violence, and torture. The music said one thing, the stage spat another.

This wasn’t an accident. Wherever beauty waits to speak, there’s an impulse to silence it. From shock-art installations to films that glorify mutilation, the pattern is the same: preempt beauty before it reaches the heart.

To desecrate something means more than to insult it. It means to attack what carries a sense of the sacred. Churches can be desecrated. Graves can be desecrated. And so can beauty. The impulse comes from a deep place. When people sense something sacred, they also sense judgment. And when they don’t want to be judged, they destroy the thing that reminds them.

This fear of the sacred is not new. The Enlightenment stripped churches of their divine aura, yet thinkers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant still recognized another way of seeing the world, not with cold calculation, but with quiet contemplation. This is where beauty begins.

Picture this. You’re walking home in the rain, lost in your own thoughts. Then the sun breaks through, lighting up a stone wall. A bird sings. For a moment, your anxieties dissolve. That is beauty. It doesn’t argue with you. It arrests you. This experience is ancient. It gave rise to poetry, to landscape painting, to sacred rituals. It still happens, though less often, because modern life has buried it under speed, noise, and alienation. But when it does happen, it reminds us that we belong.

Think of a table set for a family dinner. A clean cloth, wine in carafes, warm bread. That simple arrangement isn’t just decoration. It’s a quiet declaration: you are home. Our hunger for beauty is a hunger for belonging.

Landscape painters like Nicolas Poussin, J. M. W. Turner, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot understood this. They didn’t deny decay or death. They showed how light, even fading light, can reveal meaning in a broken world. Their paintings made the world feel like home.

W now live in an age where forces of cynicism and ugliness that once lurked in the background have come to the forefront. When we look for beauty, we often find mockery or desecration. This reveals something important. People desecrate because they still recognize the sacred. Desecration is a defense. In the presence of the sacred, we feel our lives exposed. To escape that discomfort, we destroy the thing that calls us higher.

You can see this in our reaction to death. A dead body is no longer “a person.” Yet no one looks on it as mere flesh. Something in us recoils, sensing a mystery. That is why every culture wraps death in ritual. Ritual consecrates. Desecration does the opposite.

The same happens with love. When someone falls in love, the beloved is no longer just a body. They become almost untouchable, like a figure outside time. Poets have spent centuries trying to name this feeling. It’s the human experience of the sacred.

But these are also the two points where desecration hits hardest: death and sex. Modern culture turns both into spectacle. It strips the body of reverence, reducing it to a prop. This is not neutral. It erodes our sense of dignity. When art depicts only flesh, stripped of sanctity, it denies love itself. That’s why so much of contemporary art feels loveless. It tells us the world is unlovable.

The answer isn’t moral panic or nostalgia. It’s resistance. We may have buried beauty, but we can bring it back by learning to revere the human form again and stop pretending that ugliness makes us free. It doesn’t. It only makes us numb.

Burying beauty away offers nothing. It tears down but cannot build. It strips meaning but never replaces it. When directors reduce Mozart to a backdrop for degradation, they don’t reveal new truths. They reveal their own emptiness.

This is why beauty matters. Truth, goodness, and beauty are not separate currencies. When beauty is betrayed, truth and goodness wobble too. The culture of transgression doesn’t liberate us. It leaves us drifting.

Artists who still labor for beauty, composers like Henri Dutilleux and Olivier Messiaen, writers like Italo Calvino and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn work in defiance of the noise. Their craft demands silence, precision, and patience.

But beauty isn’t only found in high art. It’s in quiet streets, warm faces, and shared rituals. It’s in the details of ordinary life that refuse to be cheapened. This is where the real contest is fought. Second-rate artists take the easy road of desecration, relying on shock. But real artists, like Wallace Stevens and Samuel Barber, return to the ordinary and make it luminous again.

The battle for beauty is not over. It happens every time someone chooses to build, paint, compose, or simply set a table with care. Desecrating beauty may scream louder but beauty endures longer. It endures because it answers a need that transgression never can. We long to belong. We long for meaning. And beauty is that bridge.

Even in a culture drunk on desecration, the quiet experience of beauty, unexpected and unforced, can still cut through the noise. The question is whether we still have the courage to bring it back.

It seems that what we call the “death of God” might be better understood as the death of our ability to see higher levels of reality. When that vision faded, beauty went with it. For if beauty is not a window to the divine, it becomes merely harmonious or decorative - and as Clement Greenberg observed, that kind of beauty is unserious for any true artist.

Traditional and modern art arise from two entirely different worldviews, with Romanticism and the Enlightenment standing between them.

Traditional art expresses universal truths to honor the divine.

Modern art expresses personal truths to honor human genius.

In traditional art, the work matters more than the artist, who often fades into anonymity.

In modern art, the artist becomes the focus of the work.

Traditional art uses shared symbols. Not to reinterpret them, but to participate in them and cultivate virtue.

Modern art turns abstract, inviting endless interpretation to find new meanings.

Traditional art is communal, speaking a shared visual language.

Modern art is individual, speaking a private one, which is why it constantly demands explanation.

Traditional art is functional, woven into life through pottery, clothing, doors, icons, and altars (temple culture).

Modern art is detached from life, existing mainly to be observed (museum culture).

Traditional artists follow craft traditions to preserve meaning and function.

Modern artists break rules to pursue originality over mastery.

Traditional art is integrated into the flow of life, harmonizing with its surroundings.

Modern art is isolated in museums, removed from daily experience.

Traditional art stands on the shoulders of giants, seeing farther through continuity.

Modern art peers into the cracks of the familiar, seeking the new through exception.

Thank you, and amen. Cynicism seeks to wrest the Divine from beauty for the vulnerability that is realized in the face of holiness. A vulgar human tendency mustachios the Mona Lisa in response to our disbelief of just how awe-striking our own makeup actually is. Possibly, the human problem is that we are more likely to suffer the fatigue of being mediocre than the fatigue of being uniquely phenomenal. Like art, we were created to reflect the Divine not as its source, but as evidence of it. It is a timely mandate to "Unbury Beauty" and seize the too-common tendency to lie to each other that we are all unlikely and unintended miracles.