Can Power and Morality Coexist?

A timeless lesson on ruling with wisdom.

Can power and morality ever coexist? Can an emperor be both feared and loved, both ruthless and righteous?

Most history books treat Ashoka and Akbar as two separate chapters in the story of India. One a Buddhist emperor from 200 BC, the other a Muslim ruler from the 1500s. Put them side by side, something remarkable happens.

Ashoka ruled with remorse. Akbar ruled with reason. One turned a battlefield into a sermon. The other turned an empire into a school. Both built more than kingdoms. They built legacies rooted in tolerance, wisdom, and restraint.

In a time still torn by identity politics and ideological battles, their stories aren't just history. They're warnings and also blueprints.

Read on. Not just to learn the past, but to rethink what it means to lead.

Most kings die as warriors or rulers, but Ashoka died as a teacher.

That sentence alone should stop you. Because when you hear “king,” you expect conquests and crowns, not sermons and sutras. But Ashoka wasn’t just any king. He was the man who stood on a blood-soaked battlefield, heard the cries of dying children, and chose never to kill again. That single decision altered the course of India and helped turn a small, regional faith into a world religion.

Let’s go back. Ashoka, born into the Maurya dynasty, didn’t begin as a sage. He was brutal. Ruthless. According to some accounts, he murdered nearly all his brothers just to sit on the throne. He built torture chambers, enacted harsh punishments, and expanded his empire through war. But then came Kalinga.

In 260 BC, Ashoka’s army crushed Kalinga, a wealthy coastal kingdom. Over 100,000 people died. The aftermath wasn’t just a political victory; it was a spiritual crisis. Ashoka walked the battlefield and saw not trophies, but corpses. Not glory, but grief. That moment broke something in him.

And that brokenness gave birth to something radical.

Ashoka didn’t just feel bad. He changed everything. He renounced violence. He turned to Buddhism, not in secret, but as state policy. Not as a private retreat, but as a national reformation. He outlawed animal sacrifices. He appointed officers of morality. He replaced conquest by the sword with “conquest by Dharma”—a moral code rooted in compassion, self-control, and truth.

This was not a soft retreat. It was a disciplined shift. He didn’t abolish the death penalty. He didn’t dismantle his state. But he used his power to spread peace instead of fear. And that power extended far.

Ashoka’s reign stretched from modern Afghanistan to Bangladesh. His reach wasn’t just territorial, it was cultural. He sent emissaries across Asia. He commissioned edicts carved into stone in multiple languages. His own children, Mahindra and Sanghamitra, were sent to Sri Lanka as Buddhist missionaries.

What emperor sends his son to convert another land without a sword?

Ashoka’s rock edicts weren’t just proclamations. They were moral handbooks. They spoke of religious tolerance, kindness to prisoners, respect for parents. This was 2,200 years ago. And yet they still sound modern.

But Ashoka was not alone in history.

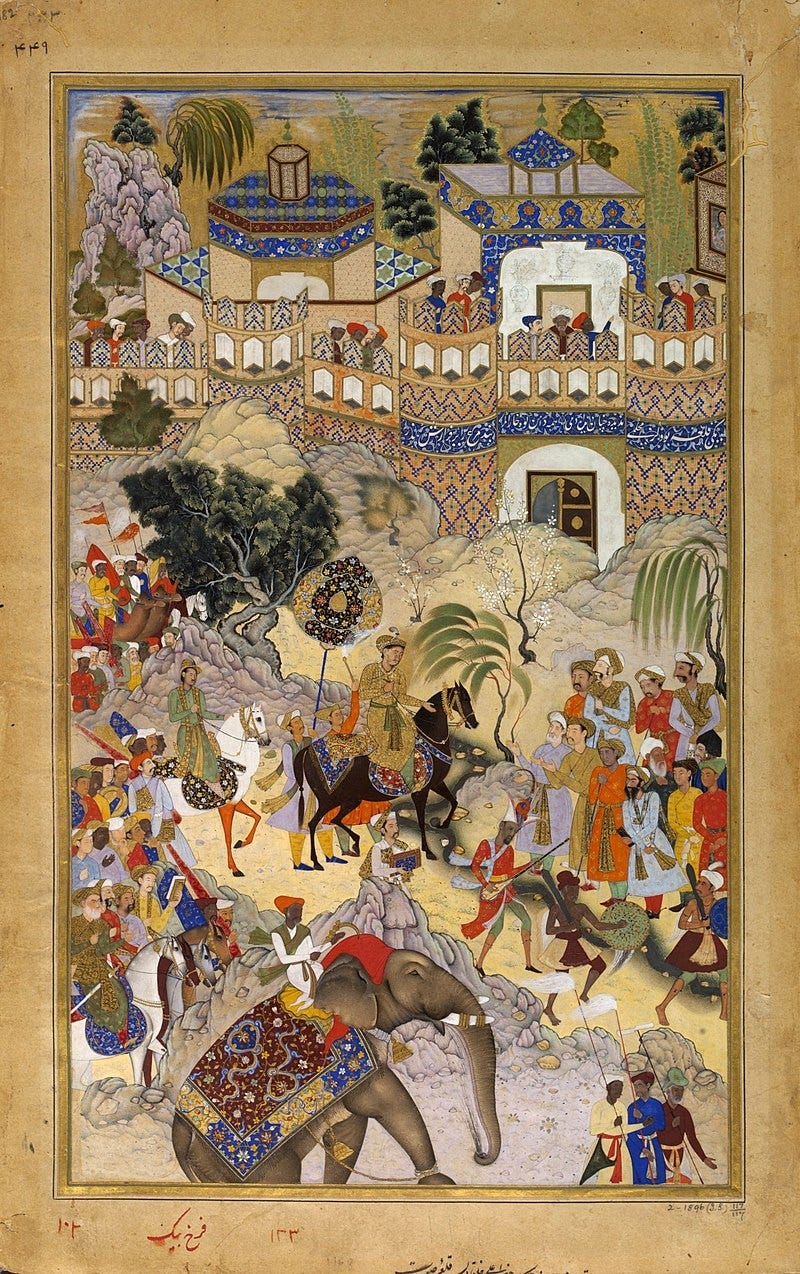

Eighteen centuries later, another Indian emperor would emerge. Akbar of the Mughal dynasty. His path was different, but his vision echoed Ashoka’s: a united India, governed by tolerance, curiosity, and reform.

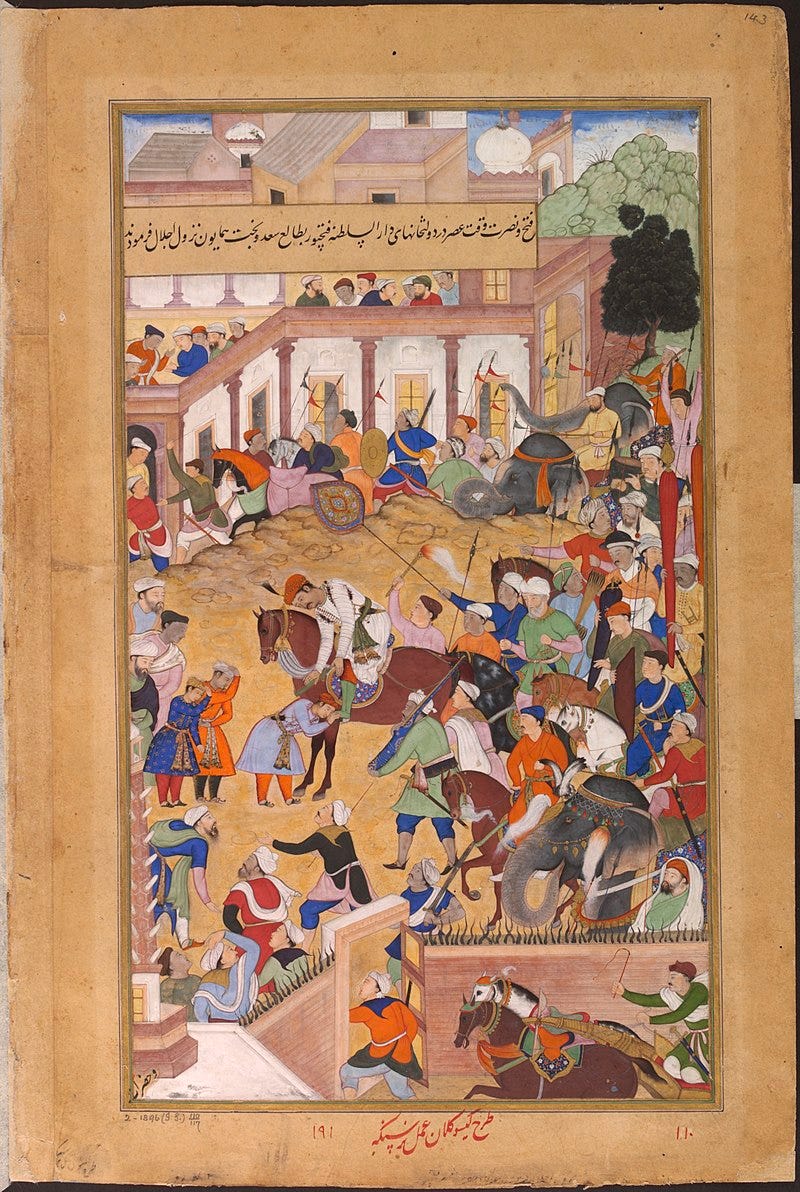

Akbar was 13 when he became emperor. A boy surrounded by war, court intrigue, and an empire held together by violence. But Akbar didn’t just inherit a throne. He reinvented the idea of rulership.

At 18, Akbar took full control. He conquered most of India but then he did something strange. He started listening.

He listened to Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Christians, even Zoroastrians. He invited scholars from every tradition into his court. He debated theology. He abolished the jizya, the tax on non-Muslims. He married Hindu princesses, not as trophies, but as political bridges. He didn’t just tolerate religion. He tried to understand it.

And that understanding shaped his policies.

Akbar restructured taxation, standardized weights and measures, and created a bureaucracy that rewarded talent, not birth. He divided the empire into revenue zones to improve fairness. He issued laws protecting farmers during famines. His government worked because it was rooted in pragmatism, not ideology.

But Akbar also dreamed big.

He founded a new religion: Din-i Ilahi. It didn’t take off, but the attempt was bold. A religion with no prophet, no book, just a commitment to ethics and reason. It was Ashoka’s Dharma in a new form: an emperor’s plea for unity in a fragmented world.

And yet, Akbar never became a monk. He didn’t renounce war. He didn’t retreat from politics. His greatness came from balance: conquest paired with conscience, centralization paired with inclusion.

Where Ashoka led through moral revolution, Akbar led through political synthesis.

Both changed India. But only one changed the world.

Without Ashoka, Buddhism may never have become global. Before him, it was one of many Indian sects. After him, it spread across Asia from Sri Lanka to China, from Burma to Korea. He made it possible for millions to hear the Buddha’s message.

In China alone, towers and relics still bear his name. Pilgrims in Zhejiang Province still visit Ashoka’s pagodas. In 2008, archaeologists in Nanjing unearthed what may be the largest Ashokan stupa in the world. Inside, they found relics said to be the Buddha’s remains. Ashoka’s legacy is physically embedded in the landscape of Asia.

Akbar’s legacy, too, remains visible in the architecture of Fatehpur Sikri, in the administrative systems that prefigured modern India, in the art and literature of the Mughal golden age. He didn’t just rule. He inspired.

But here’s the twist.

Ashoka lost his dynasty. The Mauryas collapsed shortly after his death. Akbar, by contrast, built a structure that lasted centuries. His successors, like Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, would inherit the Mughal machine.

So, who was greater?

That question is harder than it looks. Ashoka changed the human soul. Akbar changed the Indian state. One ruled with regret. The other with curiosity. One gave up power. The other learned how to wield it wisely.

If you measure by conquest, Akbar wins. If by legacy, Ashoka.

But there’s one thing that unites them both: they refused to let religion divide their people.

Ashoka, a Buddhist, protected Hindu and Jain traditions. Akbar, a Muslim, raised Hindus to high office and protected temples. They ruled in different centuries, from different religions, but believed in the same core idea that unity comes not from sameness, but from understanding.

And that idea feels rare today.

We live in an age of identity wars, cultural clashes, and historical erasure. But Ashoka and Akbar remind us that peace is not weakness, and pluralism is not surrender. It's strength. Real strength.

They weren’t perfect. Ashoka began as a killer. Akbar never stopped being a conqueror. But they grew. They learned. They tried. And they left behind a blueprint.

Not just for India. For the world.

Because leadership without empathy leads to tyranny. And power without wisdom always collapses.

Most histories stop with the story. But the real lessons of Ashoka and Akbar begin when we ask what their choices mean for leadership today. In the premium section, I break down their contrasting playbooks, remorse vs. reason, draw modern parallels, and share excerpts from their own words.