Carved Out of Silence: The Women Who Refused to Disappear

They weren’t supposed to sculpt. They weren’t supposed to last. But these women carved their way into history with stone, with fire, with defiance.

History forgot them but these women didn’t wait to be remembered. In two stories, we uncover how sculptresses and muses carved each other into memory, and how Sarah Bernhardt took the chisel into her own hands to sculpt her legacy in stone.

They Carved What History Tried to Bury

What if the most powerful legacies weren’t built by kings or popes but by women who were never meant to leave a mark?

This is a story about art, but not in the way museums usually tell it. It’s about women who shaped statues and souls, who defied expectations not with manifestos but with marble, wax, and presence. Sculptresses and their muses each one living in the margins yet refusing to stay quiet. Their stories don’t fit neatly into textbooks. They’re scattered in forgotten busts, private letters, faded portraits. But together, they hold a truth that’s been ignored for too long.

Let’s begin with Anne Seymour Damer. Sculptor, actress, and novelist. A woman born into privilege, but never content to be ornamental. She carved stone with the same force that others carved reputations and she did it while the world whispered about her personal life. But what mattered more than the rumors was the bust she made of Eliza Farren.

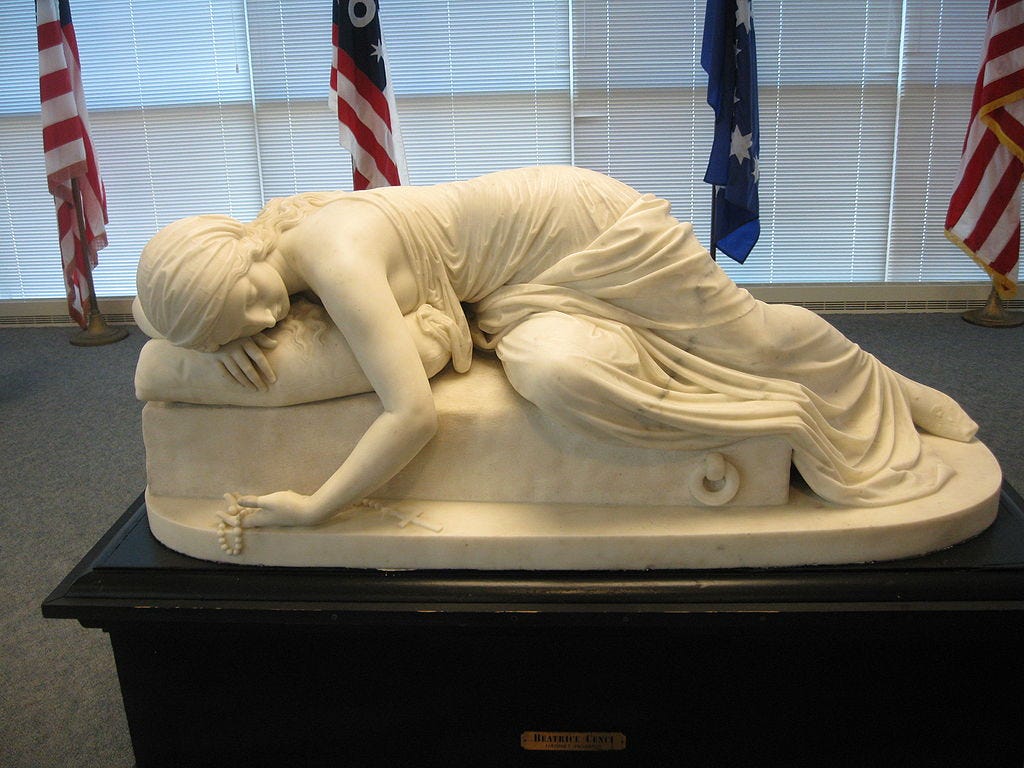

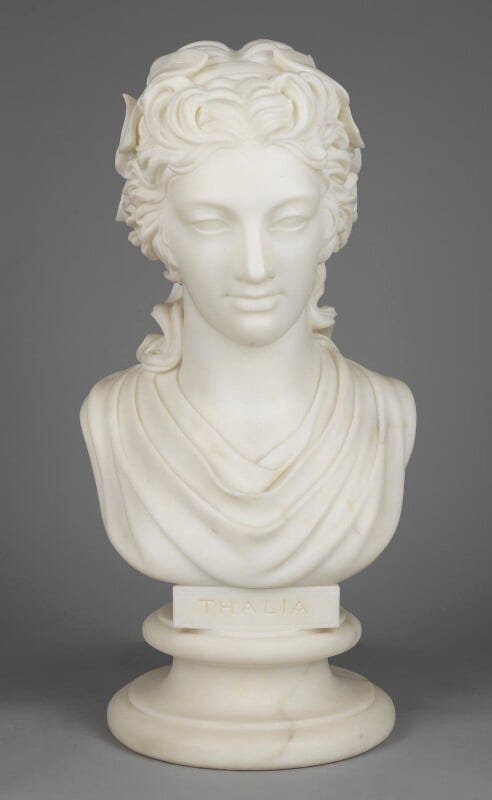

Farren wasn’t just another pretty face. She was a brilliant comedic actress who became a countess. In 1788, she and Damer staged private theatricals at Richmond House. It wasn’t just a play. It was a spectacle. Farren directed, Damer starred, and the set featured Damer’s own sculpture of Farren posing as Thalia, the muse of comedy.

Think about that for a second. A female artist sculpted her female muse. Then stood on stage, surrounded by portraits of other women she admired, performing a role about a woman struggling to hold on to love. This wasn’t just theatre—it was a statement.

And that’s where the legacy begins. Damer didn’t just sculpt. She curated an entire world where women’s beauty, power, and artistry weren’t just admired—they were made permanent.

But Damer’s career came at a cost. She was dogged by gossip. Rumors of her relationships. Scathing satirical prints. Even her friendship with Farren became fuel for public mockery. Yet Damer pressed on. She kept sculpting. She kept performing. And she kept surrounding herself with women who dared to live on their own terms.

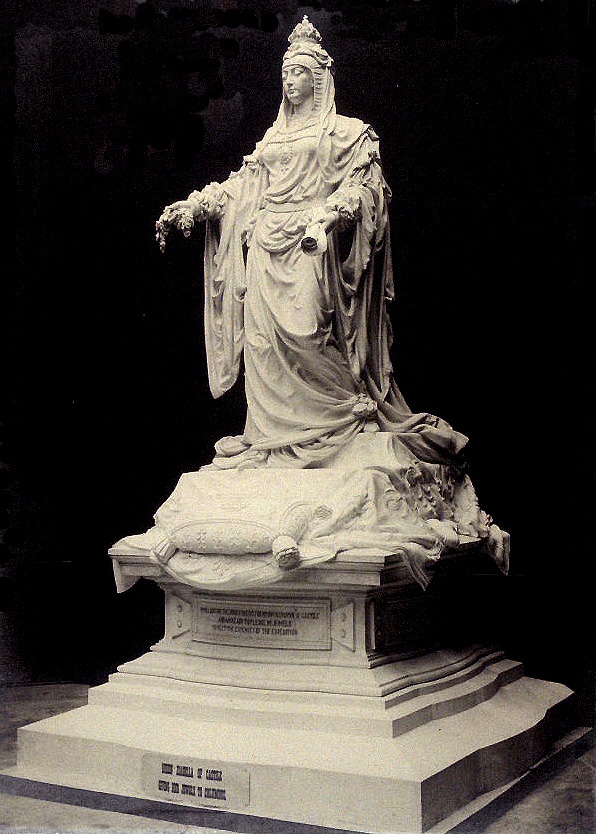

Fast forward a few decades. Another sculptress picks up the chisel, Harriet Hosmer. An American. A rebel. Raised in Massachusetts, trained in Rome. She joined a circle of women artists invited by the actress Charlotte Cushman, herself a legend of the stage. Together, they formed a kind of sisterhood.

Hosmer’s most famous work? A statue of Zenobia, the warrior queen of Palmyra. Chains draped over her body. A crown on her head. Regal, defeated, but unbroken. Critics loved the sculpture, then turned on her. Some claimed she didn’t make it herself. Others mocked her masculinity. She fought back, published a pamphlet. Took photographs of her with her studio team. She made her process visible.

Zenobia wasn’t just a historical figure. She was a mirror. In her, Hosmer saw Charlotte Cushman, who had played Lady Macbeth on stage with unmatched force. She saw Anna Jameson, the critic who wrote about Shakespeare’s heroines and celebrated fierce, brilliant women who history had sidelined.

The Queen in chains became a symbol. Not of failure but of strength under pressure. Of dignity in captivity. Of a woman who refused to be defined by what men saw.

Now shift again. It’s the 20th century. A dancer named Anna Pavlova takes the stage and reshapes ballet with her grace and intensity. Malvina Hoffman, a sculptress trained by Rodin, watches in awe. She doesn’t just admire Pavlova, she chases her with clay, wax, and camera.

Hoffman made dozens of pieces based on Pavlova. One of the most striking was a wax head, molded from a life mask. So realistic it’s eerie. So detailed it feels alive. Wax was rarely used this way. Normally, it was a starting point. For Hoffman, it became the final form.

There’s something unsettling about that sculpture. The eyes are closed. The skin seems soft. It’s almost too human. Almost like Pavlova never left. Like she’s still dancing just under the surface.

All three women, Damer, Hosmer, Hoffman, shared something rare. They didn’t just portray women. They built relationships with them. The muse wasn’t passive. She was a partner.

And that flips everything. It changes the gaze. Instead of men sculpting silent women, we see women sculpting women they knew, respected, and loved. It’s not just admiration. It’s exchange.

You can feel that in the way Damer sculpted Farren. In the way Hosmer imagined Zenobia not as a fantasy, but as a presence with weight and sorrow. In the way Hoffman froze Pavlova’s movement into a still frame without killing its energy.

And this wasn’t done in isolation. Damer was surrounded by actresses and aristocrats. Hosmer by writers, performers, and artists in Rome. Hoffman moved between salons and studios, always seeking that one subject who could hold a room.

They weren’t welcome in the academies. Most of them couldn’t study anatomy formally. They didn’t get public commissions like men did. But they worked anyway. They exhibited. They earned fame. And when that fame turned to suspicion, they found ways to endure.

Sometimes that meant burning letters, like Damer did. Sometimes it meant defending your work in print, like Hosmer did. Sometimes it meant hosting lavish theatrical parties in your own studio, like Hoffman did, and turning the whole event into art.

What these women created can’t always be measured by technique. It’s in the atmosphere. In the staging. In the gesture that lingers.

We don’t have Farren’s voice. We don’t know what Pavlova said to Hoffman. But we have their images. Their stillness that speaks of motion. Their presence, carved in stone or wax, asking us to look closer.

These weren’t isolated cases. They were part of networks of women who supported each other, modeled for each other, challenged each other to be better.

Art history likes to draw clean lines. Movements. Periods. Styles. But these women lived in the spaces between. They defied categories. Their art doesn’t just sit in museums. It flickers in private theatricals, letters, performances lost to time.

We remember male sculptors for their technique. These women should be remembered for their bravery. Because carving a woman out of stone wasn’t just about beauty. It was about permanence in a world that wanted them to vanish.

And that’s what makes their work unforgettable. Not just what they made but who they chose to see.