Did the Exodus Really Happen?

The Evidence No One Expects

For generations, the Exodus has been dismissed as myth by scholars and treated as literal history only by the devout. The standard objection was simple and seemingly decisive: “There’s no archaeological evidence.” No chariot wheels in the Red Sea. No massive Israelite encampments in the Sinai. Case closed. That objection still gets repeated but it’s increasingly out of date.

Over the last three decades, a quieter revolution has been taking place. When scholars stopped demanding Hollywood-style smoking guns and started examining texts, names, rituals, and political memories, an unexpectedly coherent picture began to emerge.

The Exodus may not have looked exactly like the Sunday-school version, but something big, something that left deep scars on both Egyptian and Israelite memory very likely did happen. Here are some converging lines of evidence that have forced even skeptical experts to reopen the file.

1. Manetho’s Hostile Egyptian Version of the Moses Story

In the 3rd century BC, the Egyptian priest-historian Manetho wrote a history of Egypt (preserved by Josephus). He describes a priest of Heliopolis named Osarseph who is expelled from Egypt with a group of “leprous” and “impure” people.

Osarseph allies himself with the Hyksos descendants in Jerusalem, rejects Egyptian gods, and leads his followers out. Later, Manetho adds, Osarseph changed his name to Moses.

This is an Egyptian counter-narrative, written from the perspective of the losers. The parallels (charismatic priest-leader, rejection of Egyptian religion, alliance with Canaan, expulsion) are so precise that leading scholars like Jan Assmann and Thomas Römer treat it as an independent Egyptian memory of the same events the Bible later reframed.

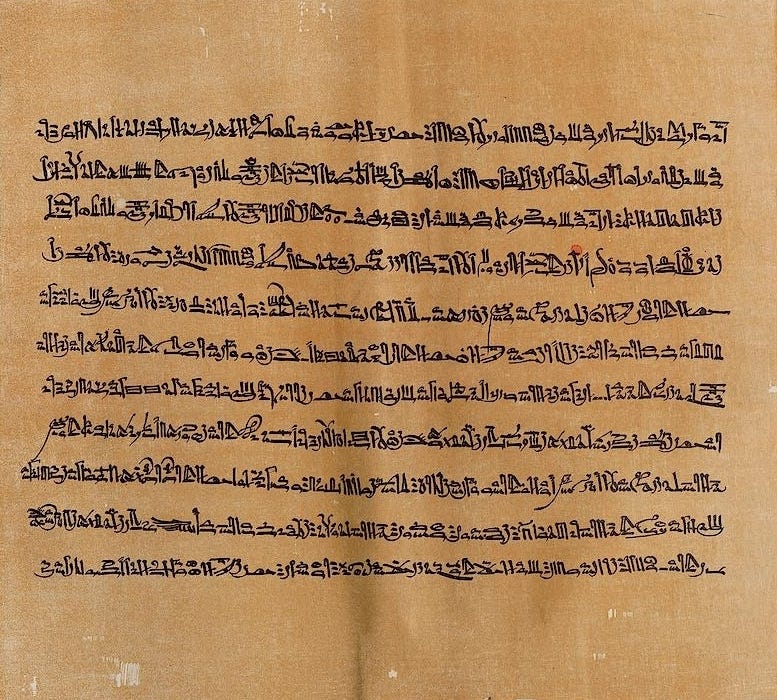

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and the Canaanite Usurper

The Great Harris Papyrus (1180 BC) is one of the longest surviving Egyptian documents. It describes a catastrophic breakdown after the death of Queen Twosret:

“The land of Egypt was overthrown from without, and every man was stripped of his possessions… A certain Syrian [Haru] was with them as chief… They treated the gods as they treated men; no offerings were made in the temples.”

Pharaoh Setnakhte eventually “destroyed the rebels” and restored order. The language, foreign infiltrators seizing power, desecrating temples, and being driven out, matches the Exodus pattern from the Egyptian side.