Greek Statues: Size Did Matter

What Greek Statues Teach About Balance

Have you ever admired a Greek statue but wondered about the size?

Size of male and female anatomy in statues was a declaration of ethos and mastery of proportions; the reason will shock you and it’s more relevant than ever for our societies today.

Ancient Greek statues command attention with their rippling muscles, poised stances, and godlike poise. Yet, amid this symphony of idealized human form, one detail often elicits a double-take or a suppressed chuckle from modern viewers: the surprisingly modest size of the penises.

Far from an oversight or a nod to prudery, this artistic choice was a deliberate stroke of genius, encapsulating the Greeks' profound reverence for proportions. It wasn't about realism or embarrassment; it was a cultural code, symbolizing self-mastery and intellectual superiority in a society that prized balance above all.

This quirky hook opens a window into the ancient Greeks' obsession with harmony, a principle that shaped not just their sculptures but their architecture, philosophy, and worldview.

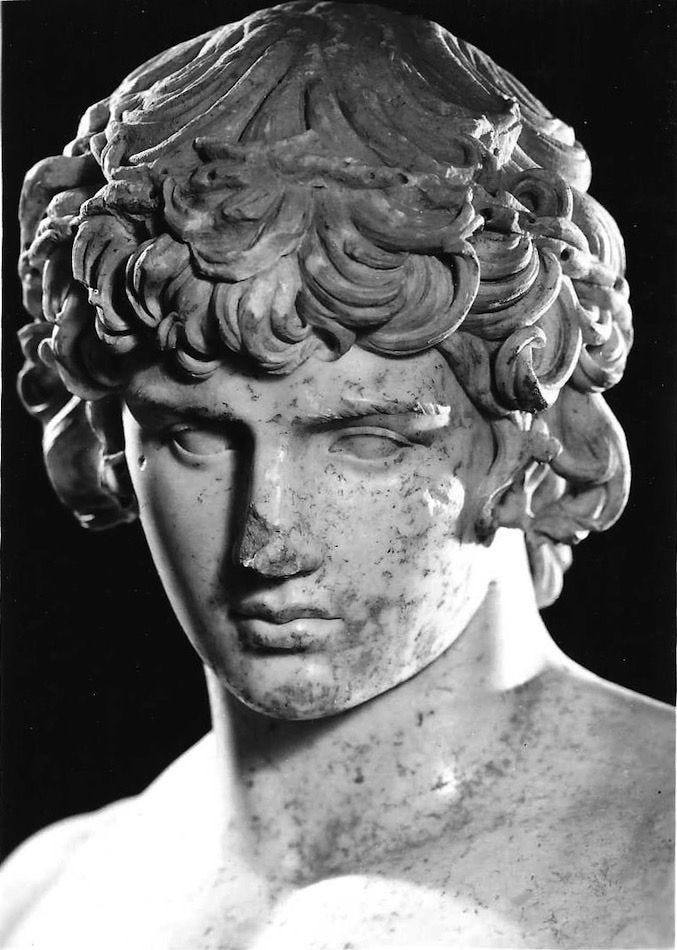

To understand why Greek sculptors opted for smaller genitalia on their male figures, we must delve into the cultural mindset of Classical Greece (roughly 480–323 BC). In this era, exhibiting a large penis was associated with barbarism, unchecked lust, and folly — traits embodied by mythical creatures like satyrs or comedic figures in theater.

In this era, a large penis was associated with barbarism, unchecked lust, and folly — traits embodied by mythical creatures like satyrs, often depicted with huge, exaggerated dicks to highlight their wild, animalistic nature, or comedic figures in theater.

Conversely, a compact, unaroused phallus represented sophrosyne, or moderation, the hallmark of a civilized man.

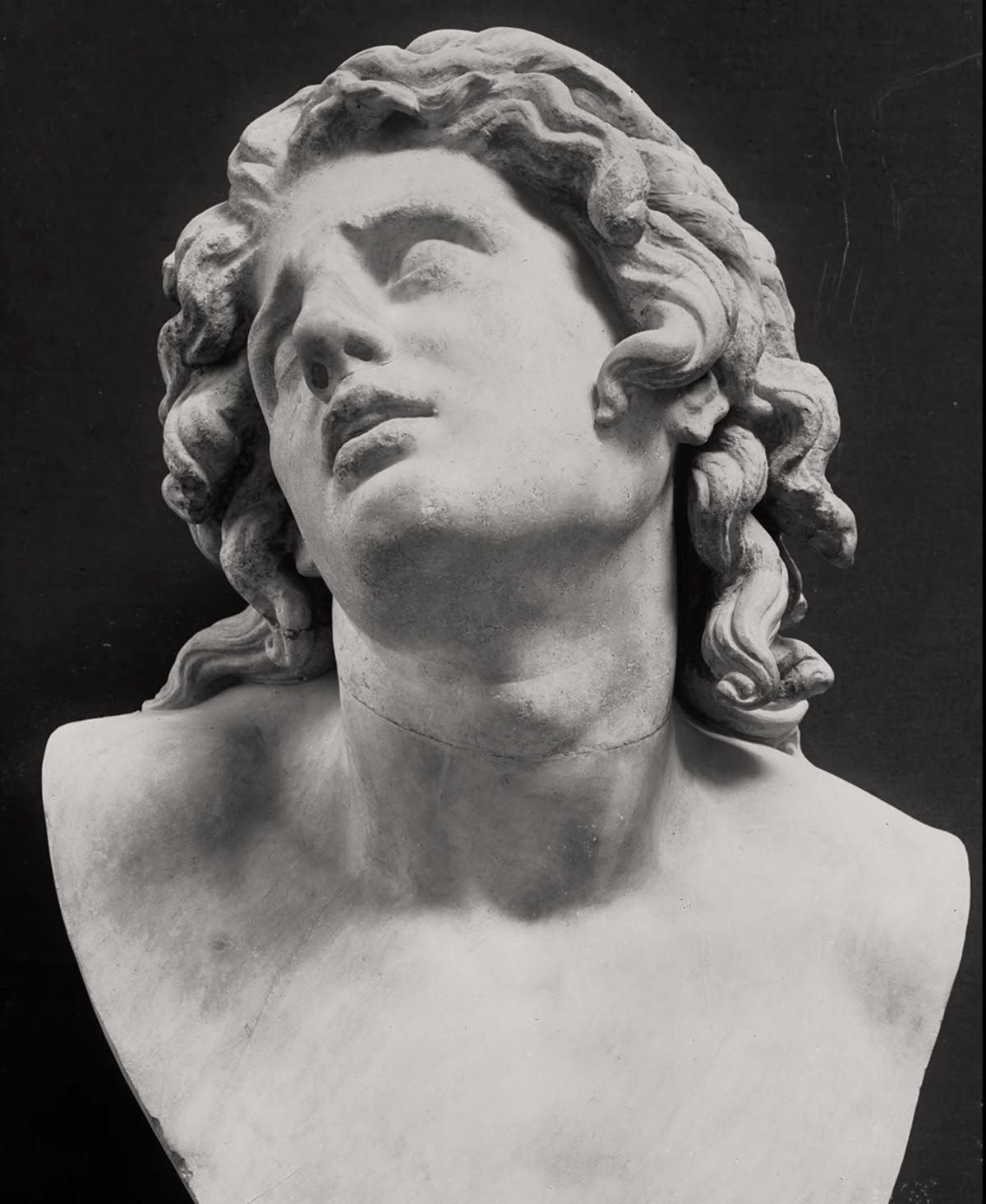

Heroes, athletes, and gods were depicted this way to emphasize rationality over base instincts, ensuring the viewer's focus remained on the body's overall equilibrium rather than any distracting element.

Take the iconic Hermes of Praxiteles (c. 330 BC), where the god's serene form exudes calm authority, his understated anatomy reinforcing the message: true beauty lies in control and proportion, not excess.

This emphasis on genital restraint was no isolated quirk; it mirrored a broader artistic canon rooted in mathematics and philosophy. Greek sculptors sought to capture not mere likeness but an elevated ideal, drawing from Pythagorean ideas that beauty emerged from numerical harmony.

The most influential system was Polykleitos' Canon (c. 450 BC), a lost treatise that prescribed precise ratios for the human body, as seen in his Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer). Here, the head comprises about 1/7 of the total height, the torso matches the distance from head to knees, and limbs follow symmetrical balances like shoulders twice the head's width.

These ratios created chiastic tension, where opposing limbs (one relaxed, one engaged) achieved dynamic equilibrium through contrapposto, a subtle weight shift that infused statues with lifelike vitality while preserving perfect symmetry.

Earlier Archaic period works (c. 700–480 BC), such as the rigid kouros statues, laid the groundwork with cruder divisions, often a head at 1/6 of the body height, but by the High Classical age, masters like Phidias and Praxiteles refined it further.

Female figures, like the Aphrodite of Knidos, among other versions, (c. 350 BC), incorporated the golden ratio (approximately 1:1.618), evident in the flowing S-curve of the torso and limbs, blending sensuality with mathematical precision.

In all cases, proportions weren't arbitrary; they reflected the Greek belief in kosmos — universal order — over chaos, turning marble into a metaphor for the balanced soul.

This proportional zeal extended beyond the human form to the built environment, where architecture became a grand-scale expression of the same ideals.

Temples weren't mere shelters for gods; they were engineered harmonies designed to evoke divine perfection and correct human perception. The Parthenon (c. 447–432 BC), atop Athens' Acropolis, exemplifies this with its facade's 9:4 width-to-height ratio and subtle refinements: columns swell slightly (entasis) to counteract optical illusions of concavity, and the base curves upward to appear flat from afar.

These adjustments ensured the structure looked impeccably proportional, even from a distance, aligning with the golden ratio found in nature and believed to underpin cosmic beauty.

Architectural orders further highlighted this precision. Doric columns, as in the Parthenon, adhered to a sturdy 1:4 to 1:8 height-to-diameter ratio, symbolizing strength and simplicity.

Ionic orders, seen in the Erechtheion, were slimmer (1:9), conveying elegance through spiraled volutes. Vitruvius, a later Roman architect influenced by Greek principles, would codify these ideas, but the Greeks themselves viewed such designs as extensions of their ethos: balanced proportions fostered societal harmony, much like a well-ordered polis.

The legacy of Greek proportions endures today, influencing Renaissance masters like Michelangelo — whose David echoes Polykleitos' canon — and modern design, from Apple's minimalist aesthetics to urban planning.

What began with a small penis on a statue reminds us that true excellence isn't in exaggeration but in measured grace. In a world often chasing excess, the ancients teach us: proportion is power.

Thank you to The Black Wolf for this fascinating article. What seems like a minor detail in Greek statues turns out to hold a timeless lesson: greatness is rooted in proportion, not excess. The Greeks believed restraint signaled wisdom, moderation, and harmony, values that shaped their art, architecture, and philosophy. That perspective still matters today, in a culture where more is often mistaken for better. Their legacy reminds us that lasting power and beauty come from balance—a truth as relevant for how we build our lives as for how they built their temples.

Your competitors are already posting.

The difference? Their words don’t land.

With ThreadSmith, yours will.

Clarity. Authority. Growth.

Message me today.

I love the detail about the head being about 1/7 of the body’s height.

The 1/7 proportion means that the head echoes the seventh day of creation, when God rests and blesses all things.

It takes on a cosmic meaning when you think about how the head is later mirrored in church domes. Same shape, same role: the highest, most “holy” part, the place where spirit dwells.

And it calls to mind Nebuchadnezzar’s dream: the statue whose head was gold, with the rest made of silver, bronze, iron, and finally clay. The head is radiant and pure, while the materials decline in value the further down you go, until you reach the fragile feet.