How America Won Its Independence Before the War Began?

Before a single shot was fired, ordinary Americans—mothers, merchants, printers, and farmers—dismantled an empire without lifting a weapon, and we buried their triumph beneath the noise of war.

How America Won Its Independence Before the War Began?

They say the American Revolution began with a gunshot in Lexington. But what if it started with a boycott instead?

For a decade before the first musket fired, Americans waged a different kind of war—a quiet, coordinated, and relentless campaign of nonviolent resistance. It didn’t make for Hollywood drama, but it shook the foundations of British power in the colonies. And yet, this chapter of history remains half-buried, overshadowed by the glamor of war.

The typical story celebrates battlefield heroes, redcoats and rebels, flags waving through smoke. But that version hides the real groundwork of independence—boycotts, petitions, smuggling, street protests, and above all, organization. The real revolution happened in courtrooms that shut down, in ports that refused British goods, and in towns where everyday people refused to comply.

John Adams saw it clearly. “The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people,” he wrote. Long before bullets flew, Americans had already begun cutting their ties to British rule—through committees, resistance networks, and a growing spirit of defiance.

It all began in 1765 with the Stamp Act. Britain imposed a tax on printed materials. The colonies responded with outrage—but not with violence. Instead, they refused to comply. Printers published without stamps. Lawyers refused to argue in courts. Merchants signed nonimportation agreements, choking off trade.

This wasn’t passive resistance. It was strategic. When British goods stopped arriving, pressure mounted in London. Merchants there, fearing economic collapse, begged Parliament to back off. And in March 1766, it did. The Stamp Act was dead—not because of war, but because of civil resistance.

Then came the Townshend Acts in 1767. More taxes, this time on glass, paint, and tea. The colonies answered again with boycotts and coordinated agreements. Boston merchants joined hands with New York and Philadelphia. Anyone who broke ranks faced public shame and social exclusion.

Resistance had become a way of life. Even women took the lead—spinning homemade cloth, refusing to buy British tea, and organizing their own pledges. In Edenton, North Carolina, 51 women publicly vowed to boycott British imports. In an era where women had little political voice, that was revolutionary.

And this revolution was local. In towns and cities, people formed Committees of Correspondence—networks that passed news, organized resistance, and filled the gaps left by failing British authority. These weren’t radicals—they were schoolteachers, shopkeepers, farmers. Ordinary people building a new order.

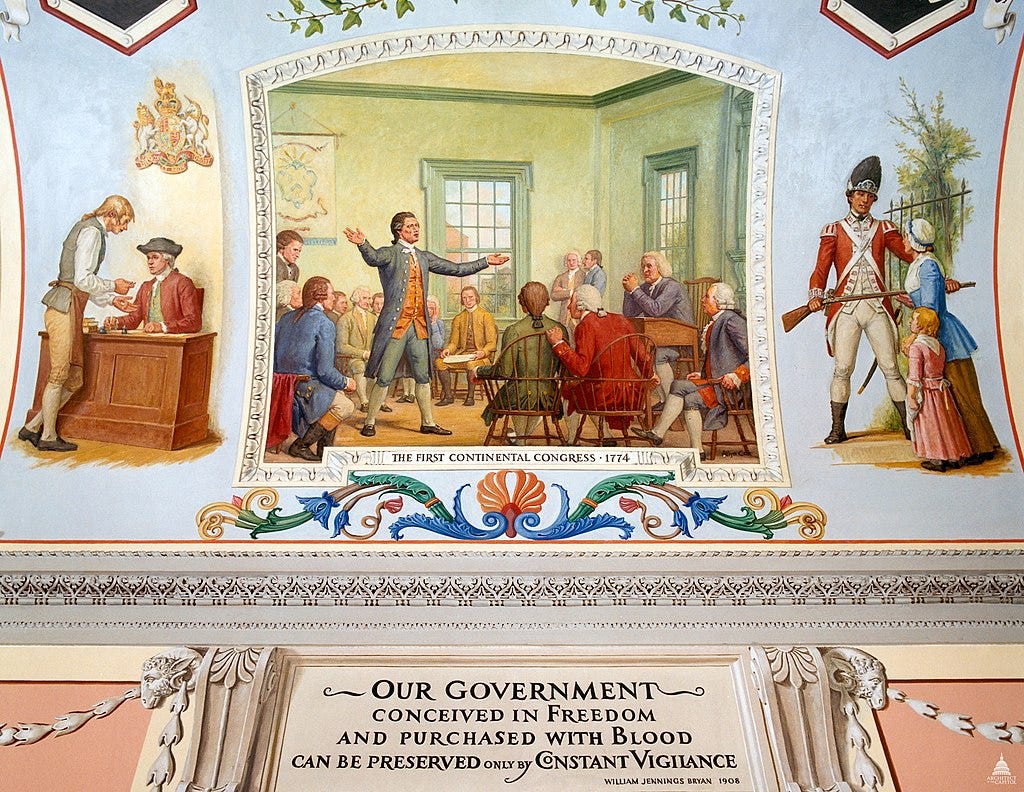

By 1774, the British tried to crush this spirit with the Coercive Acts, punishing Boston for the infamous Tea Party. But they miscalculated. The colonies responded not with chaos, but with structure. They formed the First Continental Congress and passed the Continental Association—a plan to cut economic ties to Britain entirely.

This wasn’t symbolic. It was organized economic warfare. Imports would stop. If needed, exports too. Every colony but Georgia joined. Committees were created to enforce compliance. And they worked. British goods sat on docks, unsold and unwanted.

By early 1775, the colonies had set up a shadow government. Governors lost power. Courts didn’t function unless locals said so. In many places, the British weren’t overthrown—they were simply ignored.

And the British noticed. King George called the colonies “in rebellion.” General Gage was told to arrest resistance leaders in Massachusetts. In April, British troops marched on Concord to seize weapons. There they met militia—and the war began.

But by then, the war was almost an afterthought. The revolution had already happened. The colonies had, in practice, become self-governing. What followed was a fight to defend what had already been built.

So why do we remember the war and forget the resistance?

Part of it is cultural. Americans are taught to value action—especially violent, dramatic action. Soldiers are honored. Protesters, not as much. Movies don’t show people refusing to buy British cloth. They show battles.

Another reason is that civil resistance doesn’t fit neatly into our national myth. It’s messy, decentralized, often driven by people who never became famous. But it worked. And it built the foundation for a democracy long before a constitution was written.

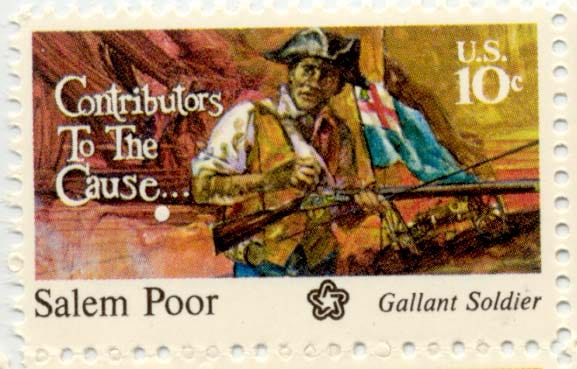

Civil resistance also empowered groups often left out of the war story. Women had real influence in boycott campaigns. Children participated in tea protests. Local committees gave power to farmers and artisans. This wasn’t a war led by generals. It was a movement led by communities.

It’s important to note: violence wasn’t entirely absent. There were occasional property attacks and even rare acts of personal aggression. But they were exceptions, not the rule. Even Samuel Adams warned, “Nothing can ruin us but our violence.”

In truth, the most effective weapon the colonists had wasn’t a musket—it was refusal. Refusing to pay, to import, to obey. That kind of power is hard to dramatize. But it’s even harder to defeat.

Nonviolent resistance allowed Americans to win allies—British merchants, dissenters, even some in Parliament. Violence would have alienated them. But civil disobedience created space for empathy and change.

Ironically, it was only after the resistance succeeded, after institutions had shifted, loyalties had changed, and independence was functionally real, that the colonies turned to war. That shift came quickly, emotionally, and without full strategic thought.

And that shift came with a cost. The war centralized power, sidelined women, empowered military over civic voices, and divided communities. Nonviolence had built unity. Violence fractured it.

In the long view, it raises the question: what might have happened if the resistance had continued without war? Could independence have come through complete withdrawal of cooperation? Could British control have collapsed under its own weight?

We’ll never know. But we do know that between 1765 and 1775, American colonists achieved a remarkable feat. With little training, no formal playbook, and enormous risk, they built parallel governments, enforced boycotts, and spread resistance across thirteen colonies.

They didn’t call it “civil resistance.” They just called it common sense. But what they did was revolutionary—not just in outcome, but in method.

So maybe the real start of the American Revolution wasn’t a shot. Maybe it was a signature on a nonimportation pact. Or a woman pouring her tea into the fire.

That version of history might not be as loud. But it’s every bit as powerful. And it’s time we told it.