How Humanity Learned to Explain the World

The Story of Thought

The oldest story humanity ever told wasn’t about war or love. It was about where we came from.

Long before the pyramids, before writing, before names like Zeus or Yahweh were spoken, our ancestors sat around fires staring at a night sky so vast it crushed language. They didn’t have telescopes or equations, but they had a mind wired for patterns. And so, they told stories to make sense of why anything existed at all. These earliest myths were our species’ first intellectual scaffolding, the framework upon which all religion, philosophy, and science would eventually be built.

The story of how human beings explained the world isn’t a collection of disconnected myths. It’s an evolution of thought. It begins in darkness with awe and ends in laboratories with algorithms. And it’s still being written.

The Age of Origins — When Wonder Was Enough

Tens of thousands of years before civilization, humans already carried cosmologies in their heads. No texts remain, but their echoes survive in the oral traditions of indigenous peoples, living fossils of thought.

Among Aboriginal Australians, the world was sung into existence during the Dreamtime by ancestral beings who carved mountains, rivers, and creatures through sacred song. This is not a primitive bedtime tale. It’s a cosmology: sound creates reality, order emerges from formlessness. Among San Bushmen in southern Africa, all creatures lived beneath the earth before emerging into the light. Caves in these stories aren’t just physical, they’re metaphors for birth, for the world’s beginning.

These myths reveal something profound. Before temples or gods, humans imagined creation as a living, intentional act. Not an accident. Not a void. But a story. That framing, the sense that reality has meaning, is the foundation of every civilization that followed.

The Age of First Explanations — Order from Chaos

The next leap came with writing. Around 3000 BCE, in Sumer, humans carved their cosmologies into clay tablets. The earliest known creation myth describes the primeval sea, Nammu, from which heaven and earth were born. The god An (sky) and Ki (earth) produced Enlil, who separated the two realms and set the cosmos in order. Humanity was later fashioned from clay and divine blood, not as masters but as laborers for the gods.

This is the first clear example of thought stepping beyond awe. The world wasn’t just mysterious. It had structure, a beginning, an order, and a hierarchy. The gods are architects. The cosmos has an instruction manual.

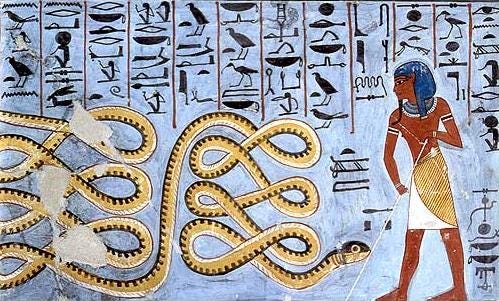

This pattern spread like an intellectual contagion. In Babylon, the Enuma Elish (18th–12th century BCE) told of Marduk defeating Tiamat, the chaos-dragon of salt water, and creating the world from her corpse. In Ancient Egypt, the god Atum rose from Nun’s dark waters and spat out the first deities, bringing light to chaos.

The language is mythic, but the logic is precise. A structured universe reflects structured societies. These myths mirror what was happening on the ground: city-states forming bureaucracies, temples organizing surplus, rulers legitimizing power by aligning themselves with cosmic order. Myth was not separate from politics or science. It was their foundation.

The Age of Consciousness — When Humans Realized They Could Act

Before gods built worlds, humans learned to tame fire. And from that act came one of the oldest myths of agency: Prometheus. In the Greek telling, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to mortals, a gift that made civilization possible and cursed humanity with suffering. This mirrors a real evolutionary revolution over a million years earlier. Mastering fire meant warmth, cooked food, extended days, and protection. It made us authors of our environment.

Then came the story of Adam and Eve. Eating from the Tree of Knowledge didn’t just mark a fall from grace, it marked the birth of self-awareness. They saw themselves as naked, moral beings, separate from their world. That’s what consciousness does: it divides observer from observed.

The Greek story of Pandora opening the box adds the next layer: curiosity carries consequences. Once knowledge is opened, it can’t be shut. Fire burns both ways.

What’s happening here is seismic. Humanity’s role shifts from passive recipient of divine order to active participant in shaping it. This mental pivot is what allowed civilizations to rise.

The Age of Cataclysm and Law — How We Stabilized the World

For all their creativity, ancient societies also remembered fear. Flood myths appear across continents… Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and parallel stories in India, China, and Mesoamerica. Many likely preserve distant memories of post-Ice Age flooding events, when coastlines vanished and entire worlds drowned.

Flood myths served two purposes. They explained environmental trauma and warned future generations. Myth here acts like civilizational hard drive storage.

But human societies didn’t only remember disasters, they built order against them. The story of Abraham sparing his son is not a random tale. It reflects the moral revolution of the early Bronze Age: the abandonment of human sacrifice in favor of symbolic offerings. It’s a story about what not to do anymore.

Then comes Moses. The giving of commandments is both spiritual and administrative. Codified law was a civilizational technology allowing complex societies to function beyond kinship ties. For the first time, order did not depend solely on a king’s whim or a god’s storm. It could be written, repeated, enforced.

This is one of the most important transitions in the history of thought: from myth as explanation to myth as governance.

The Age of Reflection — The Human Mind Becomes the Arena

Around 800 to 200 BCE, something remarkable happened across multiple civilizations: humanity started asking questions about itself. This period, often called the Axial Age, saw parallel intellectual movements in Greece, India, China, and the Near East.

In India, Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita revealed to Arjuna the structure of cosmic duty, dharma, and cyclical time. In China, early Daoists explored harmony between the human and natural order. In Greece, philosophers like Heraclitus and Pythagoras sought universal principles behind change and number.

And in India again, Gautama Buddha rejected speculative cosmology altogether. Instead of asking “Where did the world come from?” he asked “Why do we suffer?” and “How do we end it?” This was a radical inversion of the earliest myths: truth wasn’t just out there; it was in here.

The Axial Age marks the point when myth matured into philosophy. Humans began to question their own stories.

The Age of Salvation — Destiny Replaces Origin

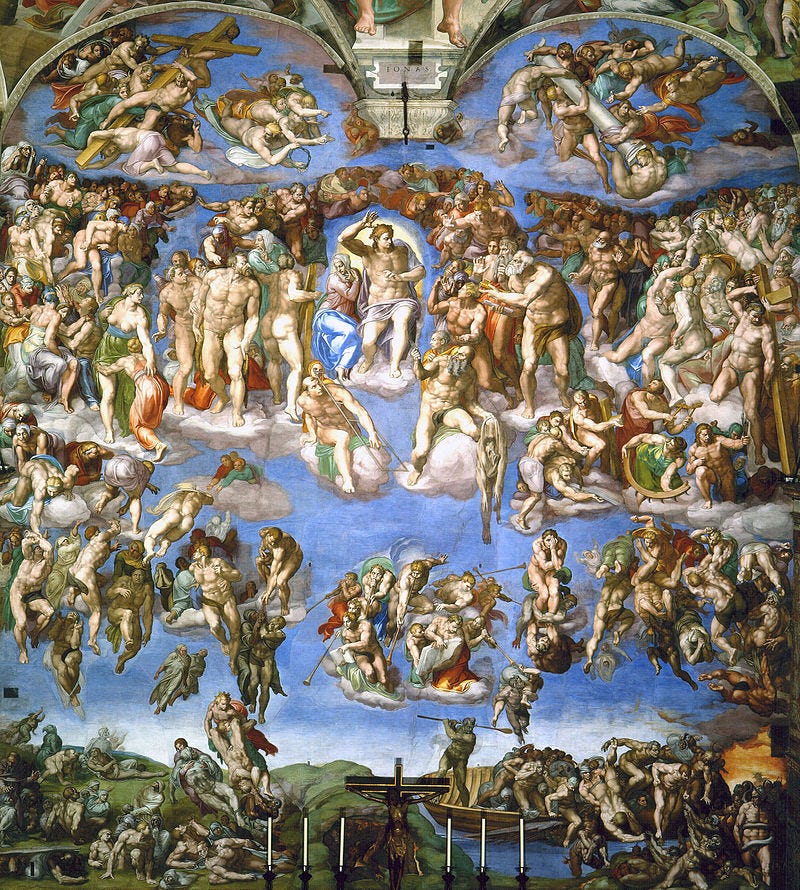

By the 1st century CE, the intellectual spotlight shifted from beginnings to endings.

The story of Jesus’ resurrection addressed a question as old as firelight: what happens to us when we die? Unlike creation myths, resurrection offered a promise, not just an explanation. It was a story of transcendence, a vision that death is not a wall but a door.

This emphasis on destiny, not just origin, became central to Christianity’s expansion across the Roman world. It answered a deeply human hunger for meaning in suffering and continuity beyond death.

In the 7th century, Muhammad closed the prophetic era in Islam, uniting revelation with a complete social, legal, and moral system. Religion was no longer just a cosmology or philosophy. It became a total worldview capable of organizing civilizations for centuries.

The Age of Synthesis — Faith Meets Reason

When the Roman world crumbled, its intellectual legacy did not. It migrated to monasteries in Europe, to translators in Syria, to philosophers and scientists in Baghdad, Córdoba, Alexandria, and beyond.

Between the 8th and 13th centuries, human thought underwent one of its quietest but most transformative phases: the systematic reconciliation of revelation and reason.

In the Islamic world, the translation movement preserved and expanded Greek, Persian, and Indian intellectual heritage. Thinkers like Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes fused Aristotelian logic with theological inquiry. House of Wisdom in Baghdad became a hub of mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy. This was the era when religious cosmologies were expanded with systematic reasoning, birthing a proto-scientific worldview.

In medieval Europe, this intellectual inheritance arrived through translations of Arabic and Greek texts. Scholastic philosophers like Thomas Aquinas attempted to harmonize faith with logic, an effort most famously seen in his synthesis of Christian theology with Aristotelian philosophy.

This period also witnessed early universities emerging in Bologna, Paris, and Oxford. Thought was becoming increasingly institutionalized. Debate and disputation replaced revelation alone as the sole path to truth.

The Age of Synthesis didn’t reject myth or faith. It sharpened them through logic, argument, and observation. It set the stage for something entirely new. The Renaissance.

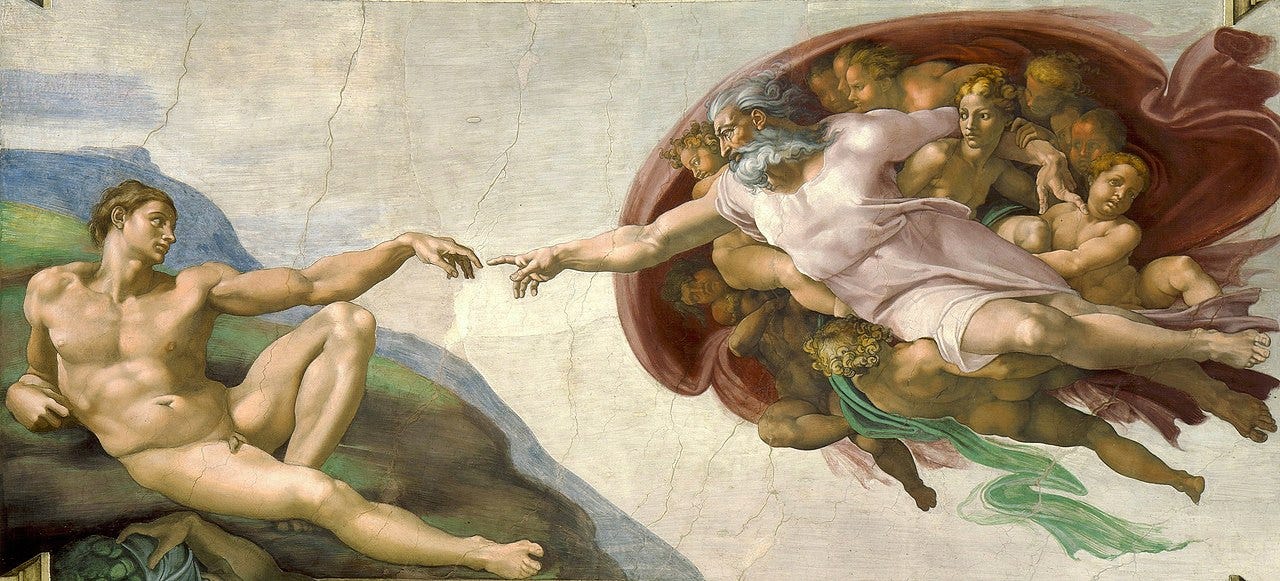

The Age of Self-Divinization — Man as Maker

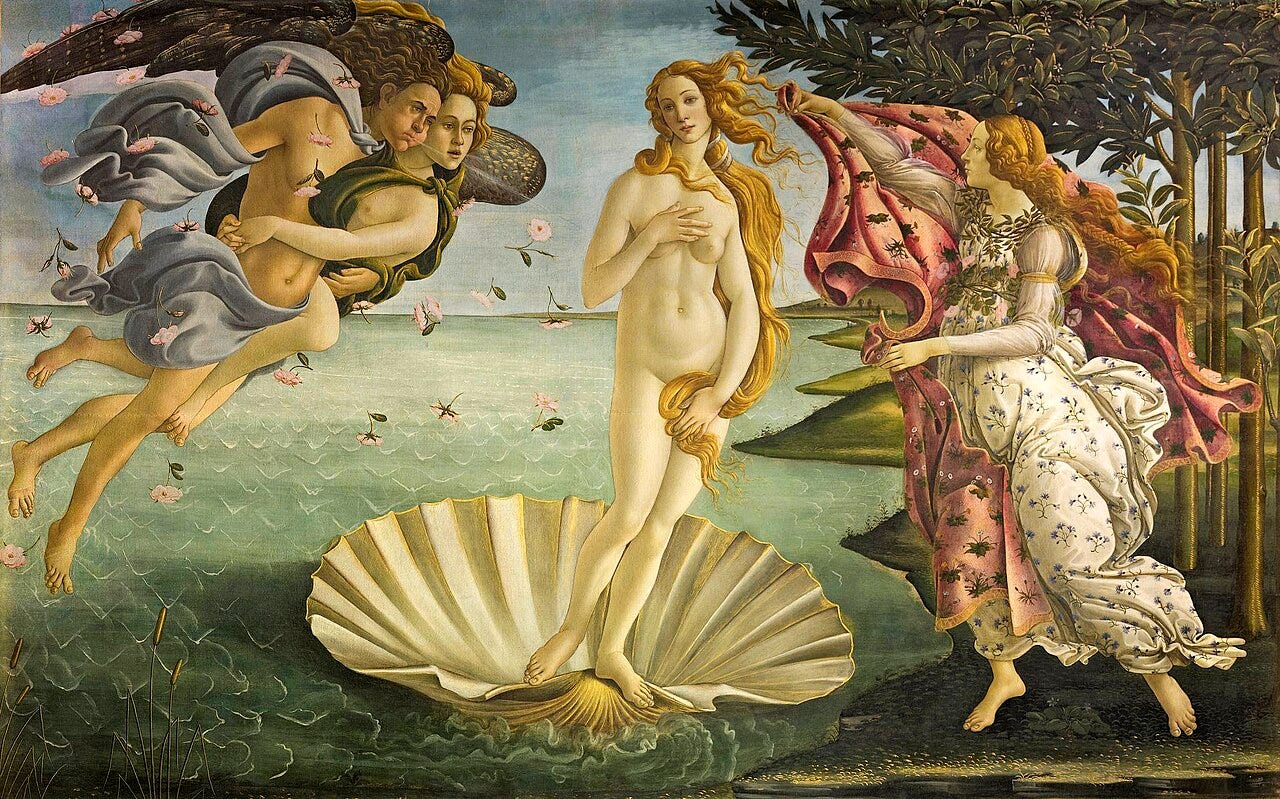

The Renaissance detonated like a cultural supernova. Between the 14th and 17th centuries, Europe rediscovered classical texts, rebuilt old myths, and shifted intellectual power back to human hands.

Leonardo da Vinci dissected corpses not to defy God but to understand creation directly. Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei cracked open the heavens. Artists painted not just saints, but humans — glorified, powerful, creative. This wasn’t blasphemy. It was Prometheus reborn.

For the first time, human beings weren’t just subjects in a cosmic story—they were authors. This shift, from revelation to reason, marks one of the most profound transformations in the history of thought. Myth was no longer the ceiling of understanding. It became the foundation upon which science stood.

The Age of New Creation — The Promethean Reversal

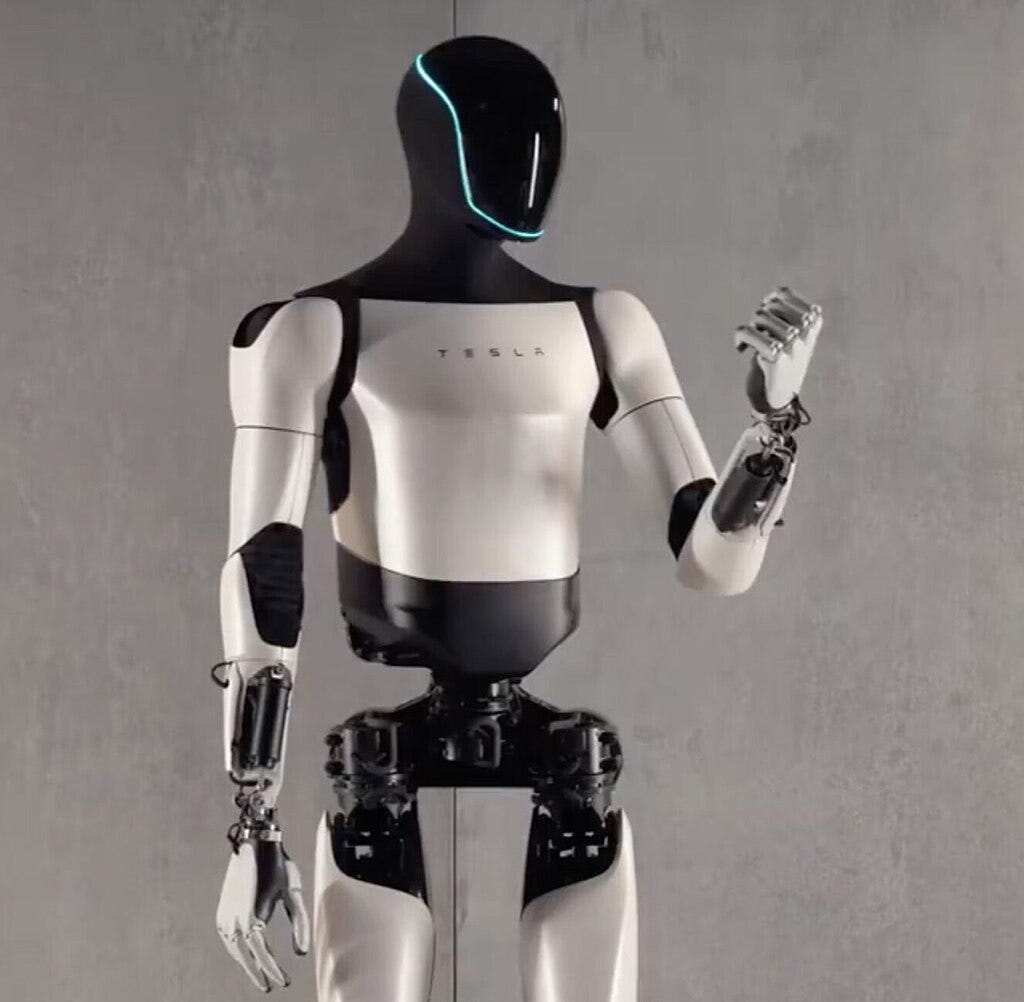

Today, humanity stands on a precipice that ancient storytellers could only imagine.

We create intelligent systems capable of learning. We manipulate DNA. We design synthetic embryos. The Promethean myth has reversed: we are now the ones giving fire to something else.

This moment isn’t just technological. It’s philosophical. For most of history, humans saw themselves as created beings, struggling to understand the mind of their makers. Now we face the mirror image: creators grappling with what they’ve made. The questions that animated the first myths — What is life? What is consciousness? What happens when creation rebels? — have returned in sharper, colder forms.

We no longer need to explain why the gods made us. We must explain why we’re making something new.

The Arc of Thought

If we look at this long arc, spanning at least 50,000 years, it’s not a collection of disconnected myths, but an intellectual evolution:

Wonder — Creation myths give meaning to a chaotic world.

Structure — Gods impose order, mirroring early states.

Consciousness — Humans realize they can act.

Law — Societies stabilize themselves with rules and shared narratives.

Reflection — Axial philosophies turn questions inward.

Salvation — Destiny and transcendence replace origin myths as core questions.

Self-Divinization — The Renaissance elevates human agency.

New Creation — AI and biotechnology bring myth full circle.

Every turning point is both a new intellectual tool and a response to an older one. Flood myths follow environmental trauma. Philosophical introspection follows civilizational complexity. Scientific rationalism grows from centuries of theological debate. And now, AI grows from the Promethean logic embedded in our earliest stories.

The Next Myth

Every age believes it’s the end of the story. It never is.

The hunters who told Dreamtime stories didn’t imagine Babylon. The priests of Marduk didn’t imagine the Renaissance. And the monks who preserved Aristotle didn’t imagine neural networks writing code.

The story of thought doesn’t end with us. The next myth will likely be about our creations, how they see us, how they explain their own beginning, and whether they, too, wonder about the sky.

What began with a song around a fire might end with an algorithm composing its own origin story.

And that may be the truest sign of how far human thought has traveled.

The myths may be ancient, but the questions are still alive. Help spread them.

Thank you. Very thoughtful and interesting.

Very enlightening. I have a few questions for humans.