How the Washington Monument Became a Symbol of Perseverance

The Washington Monument wasn’t built in a moment of triumph; it rose from decades of division, financial ruin, and near abandonment.

Table of Contents

Featured Artwork (Premium): Ginevra de' Benci by Leonardo da Vinci

Featured Architecture (Premium): National Building Museum in Washington D.C.

Happy Thursday everyone! Today’s article is brought to you by Middle-Aged Dad Trips. He is a travel enthusiast on X with a deep passion for uncovering the beauty and history of global destinations.

In the towering Washington Monument, one finds not just a tribute to the first president, but the embodiment of his struggles at the birth of the nation. Just as Washington survived the brutal winters at Valley Forge, the devastating defeat at New York, and the near collapse of his army, the mission to build and complete this monument endured its own almost-ruinous challenges.

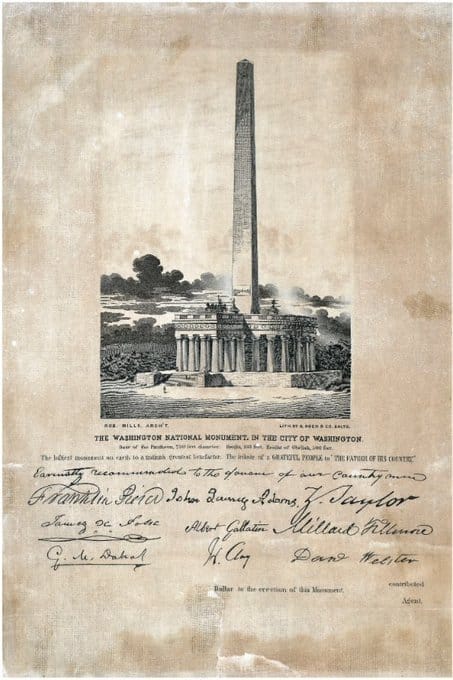

Here’s the story of how, despite the setbacks, his monument triumphed, embodying the spirit of Washington himself. The Continental Congress first proposed a monument in Washington’s honor in 1783, shortly after the Revolutionary War and well before the start of his presidency in 1789. No one made a serious effort until 1833, when volunteers formed the Washington National Monument Society. Notable figures such as John Marshall and James Madison joined the group, whose mission was to raise funds and oversee the construction.

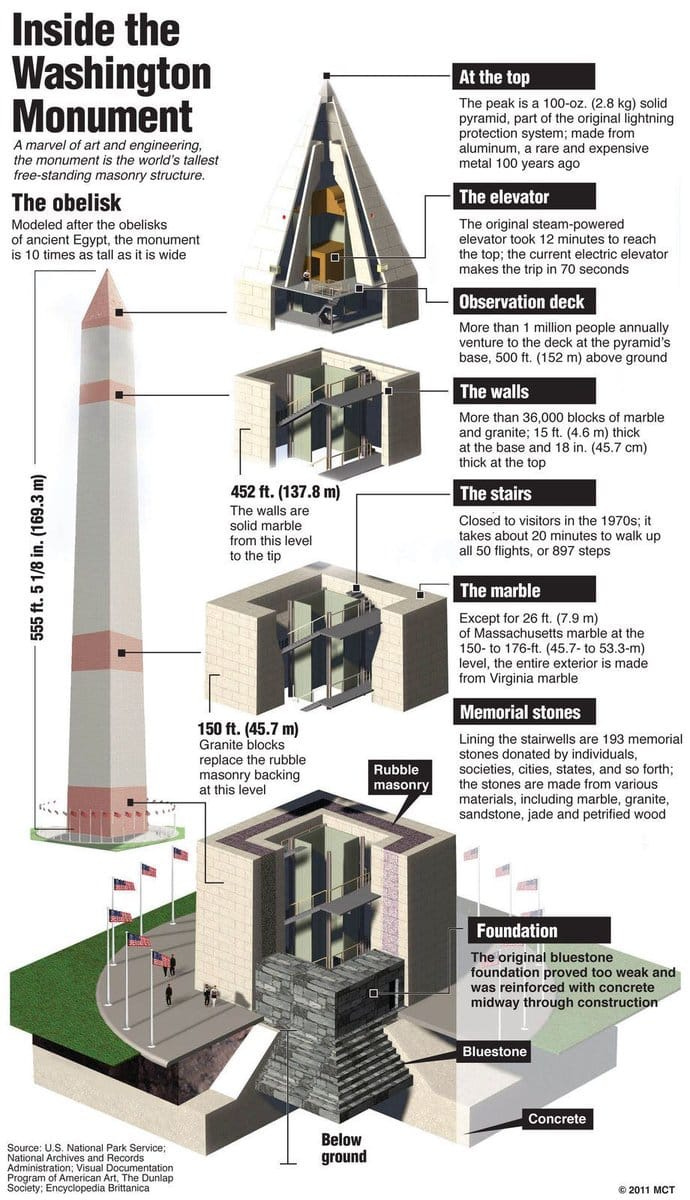

A design competition resulted in architect Robert Mills’ 600-foot-tall obelisk design winning in 1836. The obelisk’s shape, though less familiar in the United States, originated 4,000 years ago in Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. When Caesar Augustus conquered Mark Antony and Cleopatra in Egypt, he brought back the first of many Egyptian obelisks to Rome as a trophy. The obelisks remain erected throughout the city to this day.

During this time, there was a renewed interest in classical Greek and Egyptian architectural forms. Mills had already designed the Baltimore Aquila Randall Monument in the shape of an obelisk, and he also used this form in his Bunker Hill Monument competition design. Although they did not select his design, the obelisk was the winning entry.

One important practical aspect of the simple-yet-grand form is that builders can construct a monument very tall with few materials and at a relatively low cost. Mills planned to use the savings for a more lavish circular base housing, which would include a colonnade, statues, and paintings. Like how leaders laid the nation’s foundation of government, architects and planners argued intensely about the design, leading to simplified alterations. After reaching compromise, they finally began construction on July 4, 1848, agreeing to save money by initially building only the obelisk, with the additional structure to follow if funding allowed. This never happened, but the simpler design better suited George Washington’s leadership style, profound yet unpretentious.

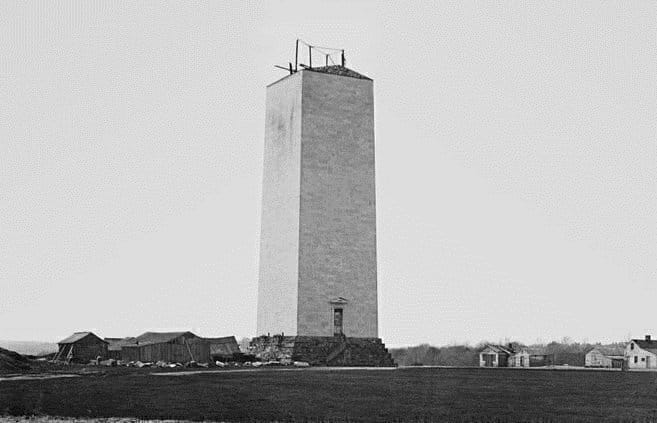

Within six years, funding ran out, forcing construction to stop. At a height of 156 feet, the incomplete monument stood in limbo for years. Locals used the site for cattle grazing, and a nearby slaughterhouse further degraded its purpose. Echoing General Washington’s own trials during the Revolutionary War, the project seemed doomed. With the looming Civil War, few cared about completing it. Mark Twain mocked it as an “ungainly old chimney” that served “no earthly use to anybody else, and certainly not in the least ornamental.”

But the conclusion of the Civil War and the fast-approaching centennial renewed interest in completing the monument. In 1876, Congress appropriated $200,000 to the project, and construction resumed in 1879. It’s not clear why, but the newly quarried materials were not a match for the originals. This left a subtle but noticeable distinction line of the resumed effort. Workers completed the monument in 1884, reaching a final height of 555 feet. This made it the tallest structure in the world, but only until 1889, when the Eiffel Tower surpassed it by almost twice. To ensure its dominance in Washington, DC, and to prohibit other significant buildings from being obscured, the Height of Buildings Act of 1910 limited new constructions to 130 feet.

Capping the monument is a 100-ounce, 8.9” tall, aluminum pyramid with the following inscriptions: -North side: “Joint Commission at Setting of Capstone Chief Engineer Brig. Gen. T. L. Casey, Corps of Engineers, Capt. George W. Davis, U.S.A.” -East side: “Laus Deo” (Latin for “Praise be to God”) -South side: “Capstone set December 6, 1884.” -West side: “Corner Stone laid July 4, 1848.” The non-tarnishing aluminum was more valuable than silver.

The capstone was the largest piece of aluminum ever cast and signified America’s wealth, innovation, and industrial capabilities. But it also had a practical function, acting as a lightning conductor to protect the monument. An internal observation deck at 500 feet was original to the monument, as was accessible by a steam-powered elevator. In 1901, an electric elevator replaced the hydraulic and cut the travel time down from 12 minutes to 10 minutes.

In 2019, workers installed a modern electric elevator, further reducing travel time to 70 seconds. There are 36,491 blocks of marble, granite, and sandstone, averaging 2.4 tons each, in the tower. Interestingly, when construction resumed, no mortar was used to secure the blocks. Instead, they rely on gravity and interlocking configuration to secure them, making them capable of slight seismic movement without catastrophic failure.

The interior holds 193 memorial stones, which passengers can see from the elevator during the descent. States, territories, cities, and even foreign countries contributed these stones to symbolize unity, honor, and respect for Washington and the nation. Arizona provided petrified wood, Alaska sent jadeite, and Greece donated a piece of marble from the Parthenon. Pope Pius IX also sent a stone from the Vatican, but members of the anti-Catholic American Party threw it into the Potomac River. In 1982, Pope John Paul II replaced it with a stone inscribed “A Roma Americae” (Rome to America).

Although builders completed the monument, new challenges awaited. Yet, like the man it honors, the obelisk stood ready to endure. In August 2011, a 5.8-magnitude earthquake struck the East Coast, shaking the monument and causing significant damage. With its epicenter just 80 miles away, this rare event posed the most serious threat in over a century. The loose-set stones absorbed much of the shock, preventing total collapse, but some shifted and cracked, requiring workers to reset, seal them with epoxy, and anchor them for stability. Engineers reinforced the topmost portion with steel braces, which remain visible from the observation deck.

After three years and $15 million in repairs, the restored monument reopened to the public in May 2014. Like Washington himself, the Washington Monument stands as a testament to resilience, dedication, and a cause greater than oneself. It embodies the belief that tenacity, perseverance, and unity lead to greatness. More than a tribute to a man, this structure represents the American way—overcoming obstacles and disagreements to achieve something enduring.

12 Reasons Why You Should Love Rome 🇮🇹

“Be Americans. Let there be no sectionalism, no North, South, East or West. You are all dependent on one another and should be one in union. In one word, be a nation. Be Americans and be true to yourselves.”

George Washington

Painting of the Day

Book Corner

The #1 New York Times bestseller. 200,000+ copies sold in three weeks.