Literature is Our Immune System

Why Civilization Lives or Dies with Its Stories?

The First Story We Still Remember

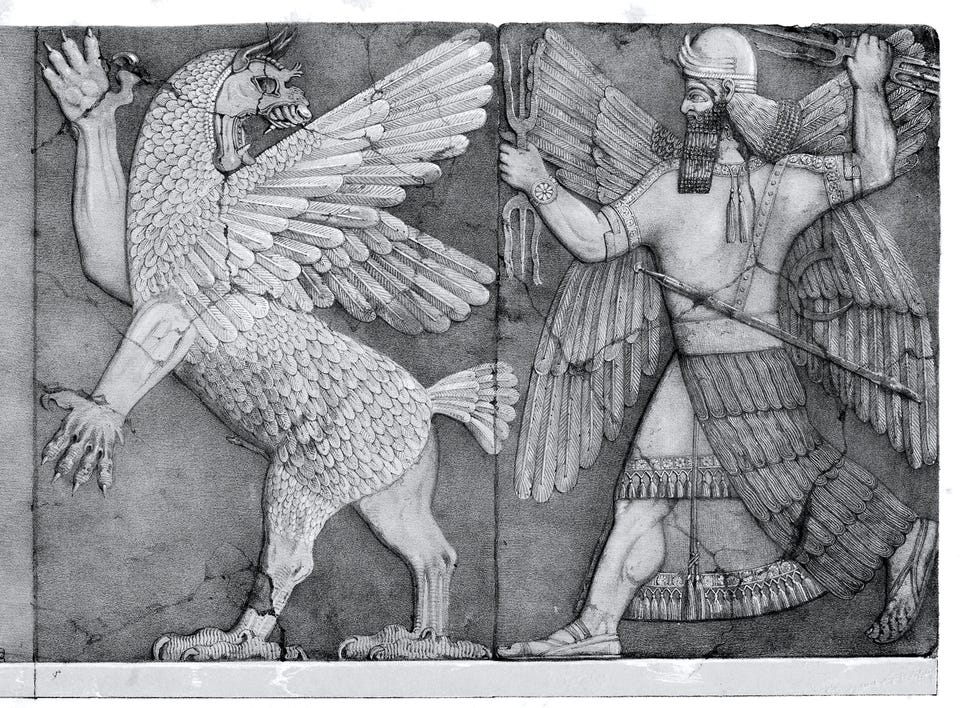

Civilizations don’t begin with armies or cities. They begin with stories. The first tale we know is not about kings or laws, but about a restless man in Uruk who could not accept death. A soldier returned from war, scarred and hollow-eyed, carrying only memories of battles no one at home could understand. He told his story, and it grew. Soon it was no longer just his grief, but the grief of a people, reshaped into gods and heroes, sung around fires, carved into clay, and written into verses that would outlive empires. This is how The Epic of Gilgamesh was born.

Why should you care? Because every stage of literature since then from Homer to Shakespeare, from the modern novel to magical realism has been the same struggle: how do we turn chaos into meaning? These aren’t just old books. They are survival strategies disguised as stories.

Mythology and the Birth of Epics

Myths were the first libraries. They were not meant to amuse, they were meant to instruct, warn, and unite. They taught a people who they were and what they must never forget.

Gilgamesh set the pattern: a king learns that victory is not immortality, but wisdom and legacy. India’s Mahabharata and Ramayana gave epic form to duty, family, and cosmic justice. Homer’s Iliad sang of rage and loss, while the Odyssey made homecoming a moral as well as physical journey. Virgil’s Aeneid turned grief into the founding myth of Rome, teaching that personal sorrow could fuel collective destiny.

Later centuries bent the epic to new needs. Dante mapped the soul’s journey from Hell to Paradise in The Divine Comedy. Milton wrestled with rebellion and free will in Paradise Lost. Luís de Camões transformed Portugal’s voyages into scripture for empire in The Lusiads.

The epic was never static. It reinvented itself to fit each era’s crises. That pattern, reinvention for survival, is the pulse of literature itself.

From Epic to Human Drama: Shakespeare

The Renaissance shattered medieval certainties. Humanism, science, and discovery demanded new forms. This is the environment William Shakespeare was born into.

Shakespeare inherited myth’s grandeur but compressed it into the human skull. Hamlet doesn’t fight gods; he fights his conscience. Macbeth’s fate is not decreed by Zeus; it is driven by his ambition. Romeo and Juliet are teenagers, yet their love burns with the inevitability of Achilles’ rage.

His revolution was language itself. English was unruly, inconsistent. Shakespeare bent it, stretched it, and filled it with words and phrases still on our tongues: “break the ice,” “wild-goose chase,” “heart of gold.” He gave English rhythm and power.

He also gave us psychology on stage. The soliloquy became the new prophecy. We weren’t watching myths at a distance anymore. We were listening to the human mind unspool its doubts, fears, and desires.

Shakespeare proved that the inner life could be as epic as war. He democratized tragedy and turned the theater into a mirror where audiences saw themselves, not just their gods.

The Rise of the Novel

By the 18th century, Europe was changing fast. The printing press spread literacy. The middle class demanded stories that reflected their lives. A new form rose to meet that demand: the novel.

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe turned shipwreck into philosophy. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela put a servant girl’s virtue at the center of a tale, daring readers to take her struggles seriously. Jane Austen dissected drawing-room manners with wit sharp enough to cut.

The novel was radical because it declared ordinary lives worthy of art. It invited readers to inhabit the minds of strangers. In doing so, it trained entire societies in empathy.

By the 19th century, the novel was the stage of civilization. Dickens exposed child labor and poverty while entertaining millions. Tolstoy braided philosophy and history into the fabric of Russian life. Dostoevsky turned psychology into spiritual drama.

The epic scale had not disappeared; it had been transplanted into the ordinary. The battlefield was no longer Troy but the human heart.

Modernism and Beyond

The 20th century broke confidence. Two world wars, industrialization, and social upheaval shattered faith in old narratives. Modernism rose in response.

James Joyce’s Ulysses turned a single Dublin day into an odyssey of thought. Virginia Woolf captured fleeting consciousness in Mrs. Dalloway. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land piled fragments of culture into a broken mosaic.

Modernism fractured language to reflect a fractured world. Like Picasso in art and Stravinsky in music, writers abandoned old forms to show brutal new truths.

But literature did more than fracture. It reinvented itself as warning and myth.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 became literature’s sharpest alarms, exposing tyranny, propaganda, and the fragility of truth. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World warned of control through pleasure instead of pain. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis turned alienation into its most haunting image.

And Tolkien, quietly in Oxford, rebuilt the epic for modernity. The Lord of the Rings was myth reborn. With invented languages, histories, and landscapes, Tolkien gave a generation torn apart by war a new vision of courage, hope, and fellowship.

Modern literature wasn’t one movement, it was a battlefield of experiments: fracturing, warning, rebuilding. Each reinvention tried to make sense of a century in flames.

Postcolonial Literature: Writing Back to Empire

As Europe redefined itself, voices from the colonies seized the pen.

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart told Africa’s story from within, dismantling colonial distortions. Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children fused myth and politics to narrate India’s fractured independence. Derek Walcott reimagined Homer for the Caribbean. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o rejected English altogether, proving that language itself is political.

Critics like Edward Said showed how literature encoded imperial fantasies. Homi Bhabha described mimicry and hybridity as strategies of cultural resistance. Postcolonial writing was not just resistance but reclamation to tell your story was to exist.

Magical Realism: Re-Enchanting the World

From Latin America came yet another reinvention: magical realism.

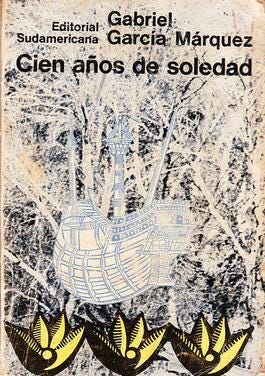

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude turned a Colombian village into a universe where ghosts walked, rain fell for years, and history repeated like myth. Borges built labyrinths where fiction folded endlessly in on itself.

What defined magical realism was not fantasy but revelation. The extraordinary revealed the truths the ordinary could not. It reminded readers that myth never dies, it hides in the everyday.

The form spread globally. Salman Rushdie used it to capture the chaos of postcolonial India. Milan Kundera used it to show the fragility of memory under dictatorship. The miraculous was now woven into kitchens, markets, and revolutions.

Summary

From Gilgamesh to García Márquez, literature has constantly reinvented itself. The epic gave civilizations their myths. Shakespeare gave voice to the human mind. The novel gave dignity to ordinary lives. Modernism fractured old forms. Orwell warned us. Tolkien rebuilt myth. Postcolonial voices reclaimed dignity. Magical realism blurred the line between myth and memory.

The forms changed. The questions did not. What is love? What is justice? How do we face death?

That is why literature matters. Not because it entertains, but because it preserves civilization’s questions.

We’ve walked through the great arc of literature — from Gilgamesh to García Márquez — and seen how each age reinvented the story to survive its own crisis. But history alone isn’t enough. The question now turns on us: what do these reinventions actually teach about civilization itself? Why do stories matter when cities crumble, when empires fade, when even languages die?

History explains the stories and the Premium section below reveals what they mean for civilization today.