Romantic Portrayals of Death in Paintings

Romanticism didn’t just paint death. It gave death a soul. It made us look at the end of life and feel awe, grief, even longing.

Welcome to today’s edition of the newsletter—where art stares death in the face and beauty rises from the shadows. We’re diving into the haunting world of Romantic paintings, where death isn’t feared but felt, mourned, and even embraced. In the premium section, we take you across Japan, exploring the culture and places that still carry the soul of a thousand years.

A boy lies lifeless on a narrow bed, bathed in cold morning light. His hair glows like gold against the pale blue of death. Scattered pages surround him—poems he wrote, unread and unpaid. This isn’t a battlefield. It’s The Death of Chatterton by Henry Wallis, painted in 1856. And it doesn’t just show a suicide. It shows a romantic myth: the young artist who dies for his genius, beauty preserved in the moment of his fall. Romanticism didn’t just paint death. It gave death a soul. It made us look at the end of life and feel awe, grief, even longing.

The Romantic movement wasn’t about balance or reason. It came as a revolt against the cold rationality of the Enlightenment. Artists wanted passion. They chased extremes. Storms. Madness. Heroism. And always—death. Not just any death. But death wrapped in beauty or meaning. They painted corpses with dignity. They showed final moments not as horror, but as poetry.

Caspar David Friedrich’s The Abbey in the Oakwood is a haunting example. Look closely. Monks carry a coffin through the ruins of a Gothic abbey. Bare trees rise like ghosts. The sun is gone. But there’s a strange peace. Friedrich doesn’t show the dead. He shows those left behind. Death is not violent here. It’s sacred. It's something you pass through.

This wasn’t new. Artists had painted death for centuries. But Romanticists made it personal. They didn’t just show saints or martyrs. They showed everyday people, caught in moments that tore your heart open. Death wasn’t always loud. It could be quiet. Lonely. Beautiful. Or noble.

Think of The Death of Sardanapalus by Eugène Delacroix. It’s chaos. Women scream. Horses collapse. The king lies on a giant bed, watching the slaughter of everything he once loved. It’s brutal. But it’s also deeply human. Delacroix paints death as a final act of control. The king doesn’t beg. He orchestrates his end like a tragic opera.

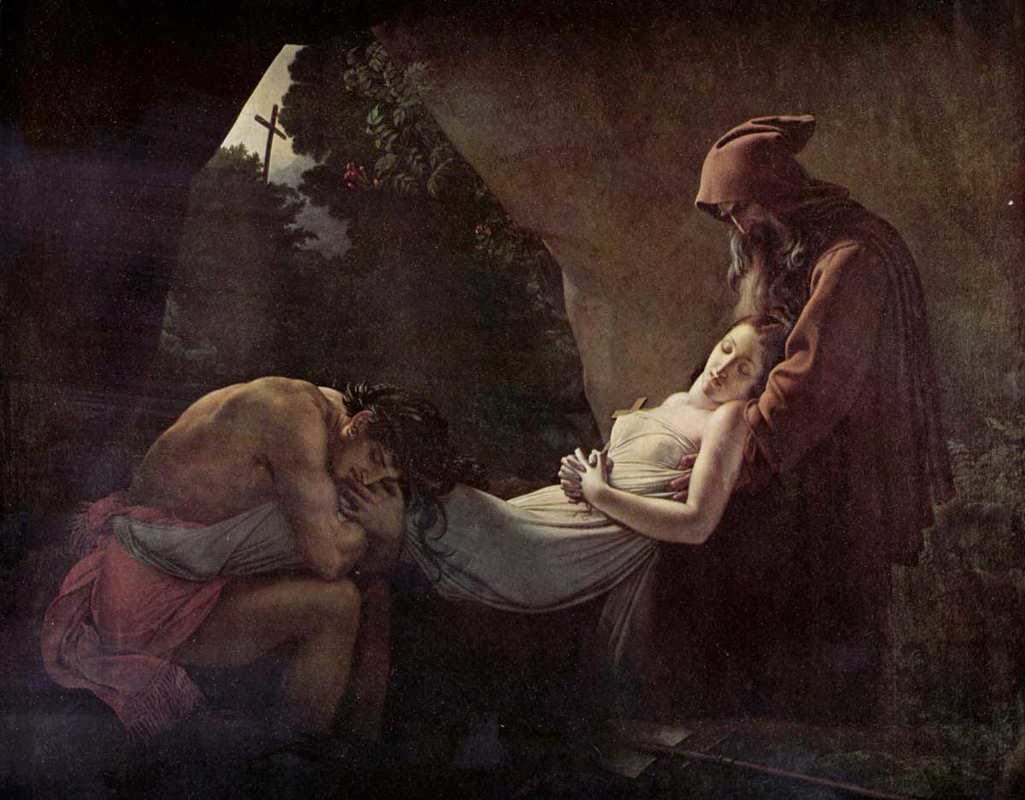

Romantic death wasn’t always about glory. Sometimes, it was just heartbreak. Ary Scheffer’s Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appraised by Dante and Virgil captures that. The lovers are dead. Killed for their sin. But they still float together, lips nearly touching, forever united in their fall. There’s judgment. But also tenderness. The painting invites you to feel pity, not just guilt.

Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa stares into the abyss. No myths. No kings. Just ordinary men abandoned at sea. Some still hope for rescue. Others are dead or dying. Their bodies form a triangle that leads your eye to a small ship in the distance. It might save them. Or it might pass them by. It’s one of the rawest portrayals of death in all of Romantic art. Yet it’s not hopeless. There’s still a sliver of light.

Romantic painters loved ruins, graveyards, fog, and twilight. These weren’t just backdrops. They reflected the soul. To them, death didn’t belong only in war or illness. It was part of nature. Part of the sublime. You see this in the way Friedrich paints cliffs, trees, and tombs. Death is always near. But never without meaning.

In Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare, death takes a different form. The woman lies limp. A demonic figure sits on her chest. A ghostly horse looms in the shadows. Is she dead? Dreaming? Possessed? Fuseli doesn’t say. But the painting captures something Romanticism understood well—how death and desire often intertwine. How fear itself can be seductive.

For some Romanticists, death was freedom. A way out. A final escape from a world too cruel. Look at Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life series. In the final panel, the old man reaches the shore. Angels wait for him. The storm has passed. It’s not sad. It’s release. The end is not an abyss but a new beginning.

Women in Romantic death scenes often symbolized purity, lost love, or tragic fate. Painters like John Everett Millais (on the edge of Romanticism and Pre-Raphaelitism) captured this with piercing clarity. His Ophelia floats in a river, flowers in hand, her body limp but serene. It’s one of the most iconic images of death in art—and it doesn’t scream. It whispers.

Even when Romantic art showed violence, it rarely reduced people to bodies. Death had a face. A story. A soul. It demanded empathy. And it invited the viewer to reflect on their own end. Not in fear—but in awe.

Romanticism didn’t glorify death as much as it made it honest. Messy. Painful. Sometimes heroic. Sometimes senseless. But never empty. Every corpse had a past. Every painting of death held a mirror up to life.

This is why Romantic portrayals of death still hit hard today. We live in a world that often hides death. Sterilizes it. Rushes past it. Romanticism lingers. It forces us to feel. It asks hard questions about meaning, love, loss, and the soul.

In the end, these paintings aren’t about dying. They’re about what it means to live knowing you will die. And how that knowledge can make every moment matter more. That’s what Romanticists gave us. A reason to stare into the dark—and still see beauty.

Poetry Corner

“La Belle Dame Sans Merci” (1819) by John Keats O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, Alone and palely loitering? The sedge has withered from the lake, And no birds sing. O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, So haggard and so woe-begone? The squirrel’s granary is full, And the harvest’s done. I see a lily on thy brow, With anguish moist and fever-dew, And on thy cheeks a fading rose Fast withereth too. I met a lady in the meads, Full beautiful—a faery’s child, Her hair was long, her foot was light, And her eyes were wild. I made a garland for her head, And bracelets too, and fragrant zone; She looked at me as she did love, And made sweet moan.

Struggling to grow your brand, write viral posts, or turn your ideas into powerful content? You don’t need more hours in the day; you need a ghostwriter who gets it.

A great ghostwriter doesn’t just write for you. They think for you, shape your message, and help you show up online with clarity and authority. Whether you're building a personal brand, scaling a business, or launching a movement, words matter.

That’s where we come in.

At Culture Explorer, we help founders, creators, and experts craft content that connects, converts, and spreads.

Contact us at admin@thecultureexplorer.com or check out our services and products to get started.