The Architecture Britain Left Behind

The architecture Britain left in its colonies stands as a lasting paradox—built to assert power, now reclaimed by the very people it once sought to rule, transforming symbols of empire into foundations of identity.

In partnership with

Table of Contents

In today’s Culture Explorer newsletter, we explore the architectural legacy of the British Empire. We’ll also delve into the rich tapestry of Indian art and culture from palaces to paintings, discover how two worlds collided—and what they left behind.

The British Empire left a deep mark on its colonies. One of the most visible and lasting impacts is in architecture. They built with the intention to control, organize, and impress. In the process, they introduced new materials, techniques, and styles that mixed with local traditions. Some of these buildings still serve essential roles today, long after the Empire fell.

In India, the British mixed Gothic, neoclassical, and Mughal styles. This created a hybrid known as Indo-Saracenic architecture. The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata is a clear example. It combines British order with Mughal arches and domes. It was built to honor Queen Victoria, but today it functions as a museum for Indian history. The style they introduced became part of the country's architectural identity.

Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus is another example. Designed by Frederick William Stevens, it was inspired by Victorian Gothic styles, but it uses Indian stonework and carving. It was a train station, but it also projected British authority. Today, millions of Indians use it. Its British origins don’t matter as much now. It’s become part of Mumbai’s story.

In Sudan, the British built administrative offices in Khartoum using Islamic elements like arches and courtyards. These weren’t just decorative. They were practical for the heat. The British adapted their designs to local conditions. Some of these buildings are still used by the Sudanese government.

Singapore’s Raffles Hotel was built in 1887. It followed a colonial style with long verandas, white walls, and wide open spaces. It was meant for wealthy Europeans. Now, it’s a national landmark. Locals and tourists both value it, not because of colonial nostalgia, but because it represents a part of the city’s growth.

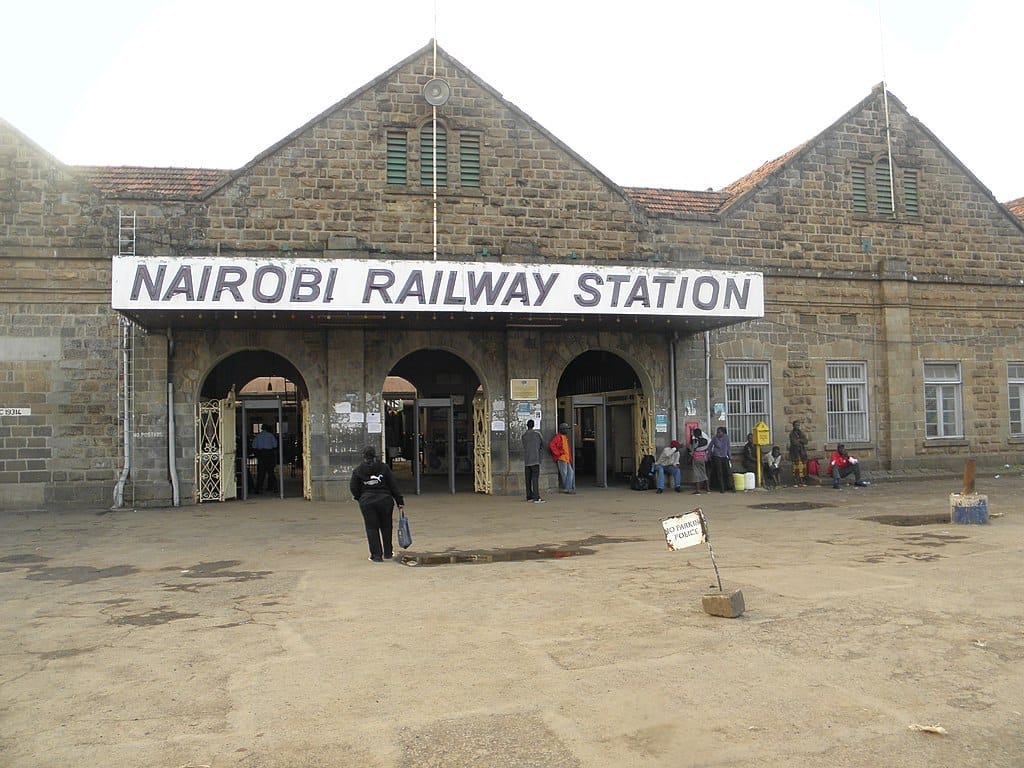

In Kenya, Nairobi Railway Station reflected Edwardian design. It was meant to show that the British were here to stay. The station helped turn Nairobi into a major city. British planning and infrastructure played a role in its urban development. Today, the city uses the railway system that began under colonial rule.

Barbados still has churches from the British era. St. John’s Parish Church is one of them. Rebuilt in the 1800s, it used Gothic Revival architecture with local stone. The church survived hurricanes and change. It’s still in use. Locals have made it theirs, even though it was originally built by colonizers.

In Lahore, Pakistan, the British built the Lahore Museum in 1894. It used a mix of Gothic and Indian styles. The building still holds historical artifacts. It also shows how British architecture blended with local traditions in a public space.

Kuala Lumpur’s Sultan Abdul Samad Building is another hybrid. It mixes Moorish, Islamic, and British design. The building used to house colonial offices. Now it’s part of Malaysian Independence Day celebrations. What was once a symbol of British control has become a symbol of national pride.

In Jerusalem, the British built the Rockefeller Museum in 1938. It’s simple and solid, using local stone. It was built to hold archaeological finds. The building respected the local style instead of trying to dominate it. That choice helped it last through political changes.

The British Empire gave the world railways, civil service systems, and a common language.

But their greatest creative contribution might be something unexpected: Indo-Saracenic architecture.

A bold fusion of East and West! 🧵

Cape Coast Castle in Ghana started before the British took over, but they expanded it. They added Georgian elements to a building with a brutal history. Today, the structure has been restored. It’s now a museum that deals directly with the legacy of the slave trade.

In Cyprus, the British built schools, courts, and police stations. They often used local stone but followed British plans. The result was a mix of British structure and Mediterranean materials. Some of these buildings are still in use by the government.

In Hong Kong, the Former Supreme Court Building is a leftover from British rule. It uses granite, a dome, and classical columns. It’s now used by Hong Kong’s own legal system. The design has remained intact, but the purpose has shifted.

Not all British architecture in the colonies was oppressive in design. Some of it respected local needs. Some adapted to the environment. Some became more useful and more appreciated over time.

Colonial rule caused deep harm, but its architecture wasn’t just about power. It also built schools, roads, and public buildings that helped shape cities. These structures have been repurposed and claimed by post-colonial nations.

The buildings are still there. They are used, maintained, and in many cases, appreciated—not for who built them, but for what they became. That legacy is complicated, but real.

"I believe firmly that it was the Almighty's goodness, to check my consummate vanity."

Lord Mountbatten

Art