The Behistun Inscription - The Message Darius Meant for the Future

Nine Lessons from an Ancient King

Every civilization thinks its warnings will outlive it, but only one empire carved those warnings into a mountainside high enough that no one could pretend they weren’t there. The Behistun inscription is a blueprint for how power collapses when truth may rot, and how a civilization fights back against that decay. When Darius ordered his story cut into the cliff at Bagastana, he wasn’t preserving history. He was trying to control the future, and in a world drowning in competing narratives, that makes his message feel less ancient and more urgent.

Most people look at the chained rebels and the triumphal pose of the king and assume the entire monument is a blunt display of domination, another example of an ancient ruler celebrating how many enemies he enslaved or crushed. That reading misses almost everything. Behistun is not a monument of submission. It’s a warning etched into stone by a ruler who believed that lies could break an empire faster than any invading army, and that unless someone carved the rules of order, truth, and legitimacy high enough that no one could rewrite them, the civilization he inherited would not survive the century.

The story begins during a period of deep instability. Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, died far from home under circumstances still debated by scholars. Into that vacuum stepped a man named Gaumata, a figure Darius describes as a fraud who impersonated the murdered prince Bardiya and seized power with breathtaking speed. The inscription insists that the empire fell under a spell of deception, with entire provinces embracing a lie because no competing narrative existed strong enough to resist it. Whether Darius’ account is accurate is almost beside the point; what matters is that he believed falsehood was the true enemy. That belief shaped everything he carved into the mountain.

The rebellions that erupted after Gaumata’s death were not minor disturbances. They spread across the Achemenid world — Elam, Medea, Parthia, Babylon, Armenia — near simultaneous explosions of doubt about who had the right to rule. What stands out in the inscription is how openly Darius records the scale of the chaos. He does not hide the number of uprisings or the force required to put them down. Instead, he turns those rebellions into proof of his legitimacy, claiming each victory as evidence that truth had reasserted itself through him. By naming each rebel, identifying each false claim, and documenting each defeat, Darius transforms a disorderly civil war into a structured moral narrative. This was his way of saying: the empire fractured because truth fractured.

The choice of the mountain itself mattered. Bagastana was already a sacred site, a place associated with divine presence long before Darius arrived. By carving his story there, he anchored his legitimacy in a location that predated Persian rule. It was a calculated act: place your version of events where the gods already stand guard, and your enemies have no ground left to challenge it. Even the placement of the figures—the king towering, the rebels bound, Ahuramazda watching above—reinforced that the political drama below was part of a much older cosmic struggle. This was not a king bragging. It was a king arguing that truth itself had chosen a side.

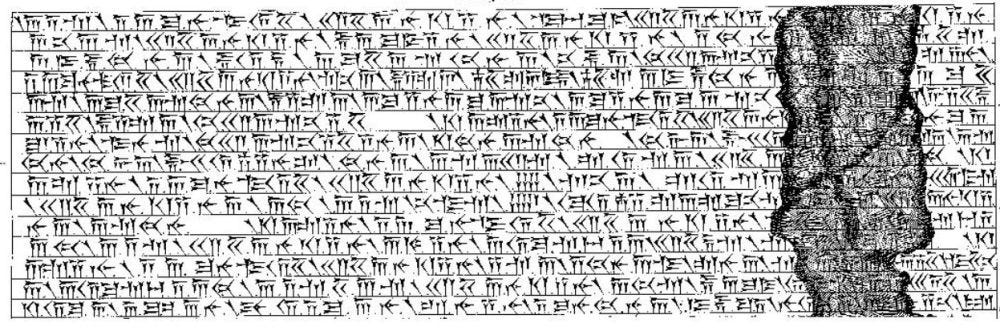

The relief is meticulous in its detail. The rebels showcase different clothing, hair, and posture, representing the different cultures that rose against him. Instead of just listing provinces, Darius displays them visually, compressing the diversity of the empire into a single scene of judgment. Yet, for all the control the image conveys, it does not revel in cruelty. Unlike the Neo-Assyrians, who carved elaborate scenes of flaying and impalement to terrify their enemies, Darius keeps violence minimized. He designed his iconography not to shock but to legitimize. The point is not barbarity. The point is the restoration of order after an eruption of falsehood.

This brings us to one of the most misunderstood aspects of the inscription. People often assume it is a glorification of domination because they see bound prisoners at the feet of a king. However, the actual text describes a more complex situation: truth was stolen from the people, chaos thrived because deception spread unchecked, and the king’s most important role was correction, not conquest. Darius claims to have restored lands, servants, and rights taken unlawfully by Gaumata. He frames himself as a restorer rather than a conqueror. Even if you distrust his motives, the message is unmistakable: in his mind, the empire’s wounds were moral wounds, and the cure was the reestablishment of truth.

The linguistic strategy of the inscription is equally revealing. Carved in Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian, it ensured that no major administrative or cultural group could claim ignorance. Old Persian signaled royal identity, Elamite handled regional governance, and Akkadian tied the empire to the deep history of Mesopotamia. Multilingual inscriptions were uncommon at this scale, and the choice to do so was deliberate. Someone might dismiss a message carved in only one language as court propaganda. A message carved in three became empire-wide orthodoxy. Darius understood that political authority meant nothing if memory was fragmented.

Behind all these elements sits a theme that has outlasted the Achemenids themselves: civilizations do not fall because of rebellion alone. They fall when no one agrees on what is true. This is the heart of Behistun, the part that modern readers rarely see because they stop at the imagery. Darius saw a world cracking under the weight of misinformation — false kings, false histories, false claims of divine right — and he responded not by building a larger army but by building a narrative that even time would struggle to dismantle.

And that is exactly where the real lessons of Behistun begin.

Everything up to this point explains how Darius framed the crisis. What comes next is what he believed would destroy the empire if no one confronted it and why he carved the actual rules for civilizational survival into stone. If you want to understand the nine lessons, he meant for the future, this is where the actual story begins.

The first lesson Behistun offers is that truth is not a luxury; it is the foundation that keeps a civilization from sinking under the weight of its own confusion. Darius frames Gaumata’s rise as a moral rupture, not a political one. In his account, the empire didn’t fracture because of taxes, famine, or cultural tension. It fractured because the people embraced a falsehood with enough conviction to reshape the political world. Darius forces the reader to understand that societies collapse first in what they believe, and only later in what they build. So, his opening lines revolve not around armies or borders but the simple claim that a lie sat on the throne long enough to poison everything beneath it. The lesson is unmistakable: once people lose the ability to recognize what is real, every institution built on that reality begins to tilt and crack.

This is where the deeper instructions begin, what Darius actually believed would destroy a civilization if left unchallenged, and why he carved those warnings into a mountain instead of a scroll.

Premium Section Break

To read the full set of nine lessons Darius carved into the cliff at Behistun and why he believed the greatest threat to an empire wasn’t rebellion but the collapse of shared reality, continue below.