The Bible Isn't About Morality - Or Even Spirituality

It's About The Map That Gives Meaning To Both

Article by Justi Andreasen, author of Reclaiming the Biblical Worldview

Most people approach the Bible as if it’s a moral instruction manual.

They read it looking for rules about how to behave. They search for principles about being good, spiritual lessons about living righteously, or inspirational stories to make them better people. And when they encounter strange genealogies, repetitive patterns, violence and failure, and wandering in circles, they get confused or discouraged.

Here’s what no one tells you: The Bible isn’t primarily about morality. It’s not even really a story. It’s a map.

This framework, the Bible as a cosmic map rather than a moral manual, comes from the work of the French Canadian theologian Jonathan Pageau and the tradition of symbolic interpretation he's helped recover. Understanding this is more important now than ever.

What Genesis Actually Describes

To understand the Bible as a map, you first need to understand the opening line:

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.”

This line is laying out the two poles of the map: Heaven and earth.

Heaven and earth aren’t just two “things” that God made.

They’re the two poles of all existence, the framework within which everything in the Bible unfolds. Heaven represents pure meaning, identity, purpose, everything that gives form and direction. Earth represents pure potential, chaos, the formless deep, everything that receives form and makes it tangible.

And everything on the map is a union of these two.

You are a union of heaven and earth. Your body is earth: matter, potential, the dust from which you were formed. Your consciousness, your spirit, the “breath of God” blown into your nostrils, that’s heaven. Every thought you think, every word you speak, is meaning (heaven) taking shape in sound waves and physical marks (earth).

This isn’t a metaphor. This is the map: the actual structure of how reality works.

The Pattern Unfolds

Once you see this pattern in Genesis, you see it everywhere in the Bible and in your life.

The six days of creation aren’t merely a chronological sequence of events. They’re a map of ontological hierarchy: a description of how being itself is organized. Darkness precedes light. Water precedes dry land. The fish in the chaos below are inverted reflections of the birds soaring in the heights above.

Everything has its place in the structure, from the lowest to the highest, from pure chaos to pure form.

And at the center, holding it all together, is humanity.

We’re the microcosm, the anchor point where heaven and earth meet. We contain both within ourselves: feet planted in dust, head reaching toward the divine.

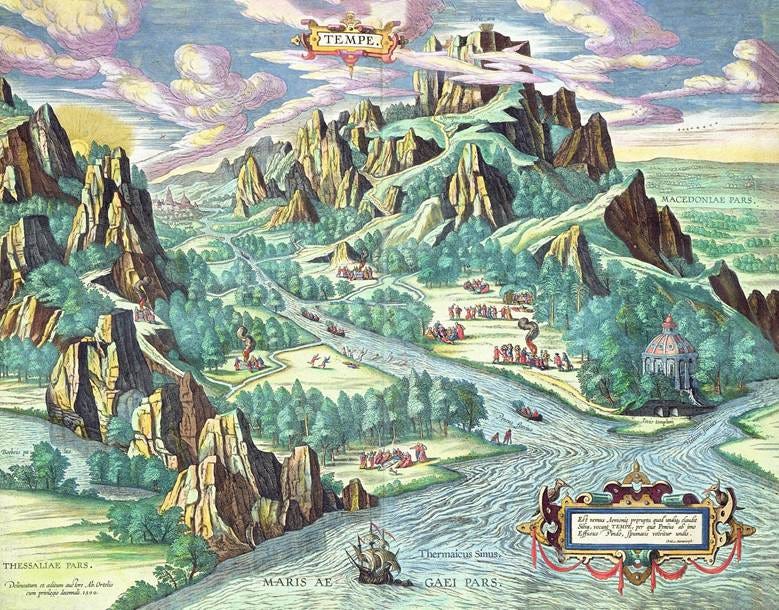

The rest of Genesis continues mapping this terrain. When things fall apart during Noah’s flood, the text describes it as a return to primordial chaos: the separation of heaven and earth, the swallowing up of order by the formless waters. When Abraham journeys, his direction isn’t random. Egypt is south, down toward earth and chaos. Haran is north, up toward heaven and meaning.

Every movement in the narrative corresponds to a position on the map.

Therefore, reading the Bible as a simple moral tale causes so much confusion. If you pay attention to what’s happening, you’ll notice that most of the characters spend most of their time doing things wrong. They’re wandering in circles, hurting themselves, breaking promises, making catastrophic choices.

The Bible isn’t telling you how to be good. It’s showing you how reality is structured and what happens when you navigate it poorly.

Not Morality, But Navigation

Think of it this way:

A geographical map doesn’t moralize. It doesn’t tell you that mountains are “good” and valleys are “bad.” It simply shows you where they are and how to navigate between them.

The elements you encounter in the Bible work the same way. They’re places on a map. And the crucial thing about any location on a map isn’t where it is, but which direction you’re moving from that point.

It doesn’t matter if you’re at the top of the mountain or in the valley. If you’re at the bottom but climbing, you’re in a better position than someone at the top who’s sliding down. Every location has a dual possibility: you can move toward life or toward death, toward order or toward chaos, toward union with God or fragmentation away from Him.

Therefore, the same imagery can have both a light side and a dark side.

Water can be baptism or drowning.

Fire can be purification or destruction.

The serpent can be wisdom or deception.

None of these things are inherently moral. They’re structural elements that reveal their meaning based on the direction you’re traveling through them.

What you’re reading now is only the outline of the biblical map. The full picture shows how the same structure that shapes Scripture also shapes your life:

Your choices

Your work

Your relationships

Your search for meaning

If you want to learn to read that structure and navigate by it, subscribe below.

Reclaiming a Biblical Worldview

The Way Through the Map

Here’s where the crucifixion and resurrection enter the picture.

If Genesis and the Old Testament lay out the map (the structure of reality, the framework of heaven and earth) then the crucifixion shows you the way to navigate it - the path, the method, and only route that actually works.

Christ descends to the absolute lowest point. He goes down into death itself, into the chaos, into the separation of heaven and earth. The crucifixion is the ultimate downward movement:

God Himself entering the formless deep, the place of total dissolution.

But this descent isn’t a defeat. It’s the pattern that reorganizes everything:

By going all the way down into death, Christ transforms death itself.

He enters the lowest point on the map not to be destroyed by it, but to plant the cross there as a pillar connecting heaven and earth.

The cross becomes the new axis mundi, the new tree of life at the center, the new ladder between the two realms.

And then the resurrection reveals what this downward path actually accomplishes: ascent. The way up is through going down. Union with God comes through complete self-emptying. Life emerges from death. Heaven and earth are reunited precisely at the point where they seemed most completely separated.

This is the road. This is how you navigate the map.

Why This Matters

When you understand the Bible is a map rather than a moral instruction manual, everything changes.

You stop asking, “What does this command me to do?” and start asking, “Where am I on this map? In which direction am I moving? What pattern is unfolding in my life right now?”

You realize that when the Israelites wander in the wilderness for forty years, it’s not just a historical event or a cautionary moral tale. It shows you the pattern of what happens when you make certain choices at certain junctures. It’s revealing how one wrong turn at a critical moment can trap you in a cycle that takes generations to escape.

You see that when Jesus says, “I am the way,” He’s not speaking metaphorically. In a literal sense, he is the way through the map. His life, death, and resurrection reveal the actual structure of how to move through reality:

How to hold heaven and earth together?

How to descend into chaos without being destroyed?

How to unite what has been separated?

The map was always there, laid out in Genesis. The pattern was always unfolding through every story, every journey, every rise and fall chronicled in Scripture. Christ doesn’t add something new to the map. He shows you how to read it, embodies the way through it, and becomes the path itself.

Reading With New Eyes

Therefore, the Bible feels so strange when you first encounter its logic.

It’s not organized according to modern narratives or moral categories. It’s organized according to the deep structure of reality: a structure built on heaven and earth, on pattern and chaos, on the union of meaning and matter.

Once you see this structure, you can’t unsee it.

You notice how every story, every law, every prophecy fits into the larger map, see the connections between Moses ascending Sinai and Christ on the cross, and understand why fish and birds appear together on the fifth day, and what that reveals about the cosmic hierarchy. You grasp why directions matter, why numbers repeat, why seemingly trivial details carry such weight.

The Bible has always been more than a story.

It’s always been more than a list of spiritual principles or moral guidelines. It’s a map of how reality is structured and a revelation of the way to navigate through it.

Genesis shows you the map. The crucifixion shows you the way. Everything else is learning to recognize where you are and which direction you need to move.

The question isn’t whether you’re good or bad, spiritual or worldly. The question is: Do you understand the structure? Can you read the map? Are you following the path?

Because the map was always real. The structure was always there. And Christ marked the way through with a cross.

Lord Christ entered in the fullness of time to show The Way through an active love, instead of a vacuous emptiness of the Tao which hints at the meaning through void. While we can achieve temporary peace with the empty room of the East, the highest level is in the active as well the contemplative. Myth is true and sometimes, like with our Lord Jesus, it really happened. The magi showed this Way was available to all.

Great article, thank you for sharing.

Is also the best owner manual for humanity