The Dawn of Thought and the Human Search for Meaning

Article 1 of The Arc of Belief and Meaning Series

Today, I begin the first article in The Twelve-Part Arc of Belief and Meaning by asking the same question humans have asked since the first fire was lit: what kind of world is this, and what does it ask of us? When I look at the earliest myths humanity told, I see a species waking up to itself.

Before writing, before cities, before gods had names, human beings sat around fires and stared into a world that did not explain itself. The sky was vast and indifferent. Nature was powerful and unpredictable. Death arrived without warning. And yet something inside us sensed that this was not just a physical environment. It was a moral one. Actions felt heavy. Guilt appeared even when no one was watching. Suffering demanded meaning.

That is where thought begins, with a quiet sense that something is missing and needs to be understood.

The earliest myths across cultures reflect this first awakening. Among Indigenous Australians, the world is sung into being. Sound does not describe reality; it shapes it. Creation is not a distant event locked in the past, but an ongoing act remembered through ritual. Among early hunter-gatherer cultures, caves are imagined as wombs, animals as kin, landscapes as ancestors. The world is alive, relational, and responsive.

At this stage, explanation and belonging are the same thing. To explain the world is to know how to live inside it.

As human societies grow larger, something changes. Writing fixes memory. Distance enters consciousness. The world can now be described from the outside. In the early civilizations of Sumer, Babylon, and Egypt, creation becomes structured. Realms are separated. Hierarchies are established. Order replaces openness.

These myths mirror social reality. Cities require administration. Surplus requires control. Power requires justification. The gods begin to resemble kings. Chaos becomes the enemy. Stability becomes sacred.

This is a gain, but it narrows something vital. Mystery shrinks. The world becomes safer, but less intimate. Explanation begins to serve control as much as understanding.

Greek mythology emerges at this tension point, and this is where something crucial happens. The Greeks do not abandon myth, but they humanize it. Their gods are not distant forces or moral abstractions. They are passionate, flawed, jealous, creative, cruel, and curious. Zeus cheats. Hera resents. Athena reasons. Apollo seeks order. Dionysus dissolves it.

For the first time, the divine mirrors the human psyche itself.

Greek myth does not simply explain the world; it explores inner conflict. It recognizes that human life is shaped by competing drives: reason and impulse, order and chaos, restraint and excess. Tragedy becomes a form of knowledge. The Greeks understand that insight does not always save you, and that wisdom often arrives too late.

This is a profound advance. The universe is no longer just something that happens to us. It is something we struggle with internally.

Greek philosophy grows directly out of this mythic soil. When thinkers like Heraclitus, Plato, and Aristotle begin asking about reason, form, and purpose, they are not rejecting myth. They are disciplining it. Logos emerges as a tool for clarity, not as a weapon against meaning.

While this is happening in Greece, India is exploring a different dimension of the same problem.

Hindu thought does not ask only where the world came from. It asks why existence repeats itself. Time becomes cyclical. Reality unfolds through creation, preservation, and destruction. The self is not fixed. It migrates, learns, forgets, and returns. Desire binds the soul. Action has consequence. Karma is not punishment; it is continuity.

This introduces something radical into human thought: responsibility without surveillance. Moral cause and effect do not depend on divine moods or human courts. They are woven into reality itself. The Upanishads push this even further. They turn attention inward and ask whether the self we cling to is real at all. The idea that identity itself may be provisional is one of the most daring thoughts humanity has ever produced.

Buddhism takes this insight and sharpens it further. The Buddha refuses to speculate about creation or gods, not out of ignorance, but discipline. He focuses on suffering. Why it arises. How attachment fuels it. How it can end. This is a monumental shift. Meaning is no longer located in the structure of the universe, but in the condition of the mind. Liberation does not come from understanding the cosmos. It comes from understanding craving, fear, and illusion.

What Buddhism contributes to human thought is restraint. Not repression, but clarity. The idea that not every question must be answered to live well. That insight itself was a form of freedom. While these traditions deepen interior life, the Hebrew tradition does something different. It moralizes history.

Judaism introduces covenant. Time becomes directional. Actions matter because they shape what comes next. God is not just a cosmic force or a mirror of human emotion. He is a witness. Law emerges as lived obligation and justice becomes central.

This is where I read the story of Adam differently. To me, Adam is not about forbidden knowledge, it is about the arrival of conscience. Eating from the tree marks the moment human beings become aware of themselves as moral agents. Shame appears. Responsibility begins. This is not a fall from intelligence. It is the birth of it.

Evolution does not end with the body. It continues in awareness. The story of Abraham then marks another decisive step. Early civilizations practiced child sacrifice not out of cruelty, but terror. The universe felt unstable. Blood was believed to hold it together.

Abraham interrupts this logic. He raises the knife and then it is stopped and his son is spared. Something new enters the moral world. Fear no longer gets the final word. There are limits, even on what humans think the divine demands. This is one of the clearest moments where conscience asserts itself against survival panic.

Christianity internalizes this moral seriousness. God does not merely command justice. He suffers injustice. Meaning is no longer found only in obedience or law, but in transformation through suffering. This addresses a problem law alone cannot solve. What to do with pain that is undeserved?

Christianity gives suffering weight instead of explanation. It tells people that endurance itself can be meaningful, even when the world remains broken.

Islam arrives as a closure rather than a replacement. The idea of Muhammad as the Seal of the Prophets is not just theological, it is philosophical. Revelation is complete. Humanity has been given sufficient guidance. There will be no endless stream of new corrections from the divine.

This shifts responsibility decisively. Interpretation, action, and memory now rest with human beings. Islam unites belief, law, and daily life into a coherent whole, while also signaling that humanity must now live with what it has been given.

I read this as a form of moral adulthood. God is not removed, but dependency is reduced. Humanity is no longer waiting for rescue through new revelation. It is expected to govern itself.

From here, the rise of philosophy, science, and humanism follows naturally. Reason grows not as rebellion, but as confidence. Humans test the world directly. They measure, experiment, and build. The question shifts from meaning to mechanism.

Now we face a final mirror.

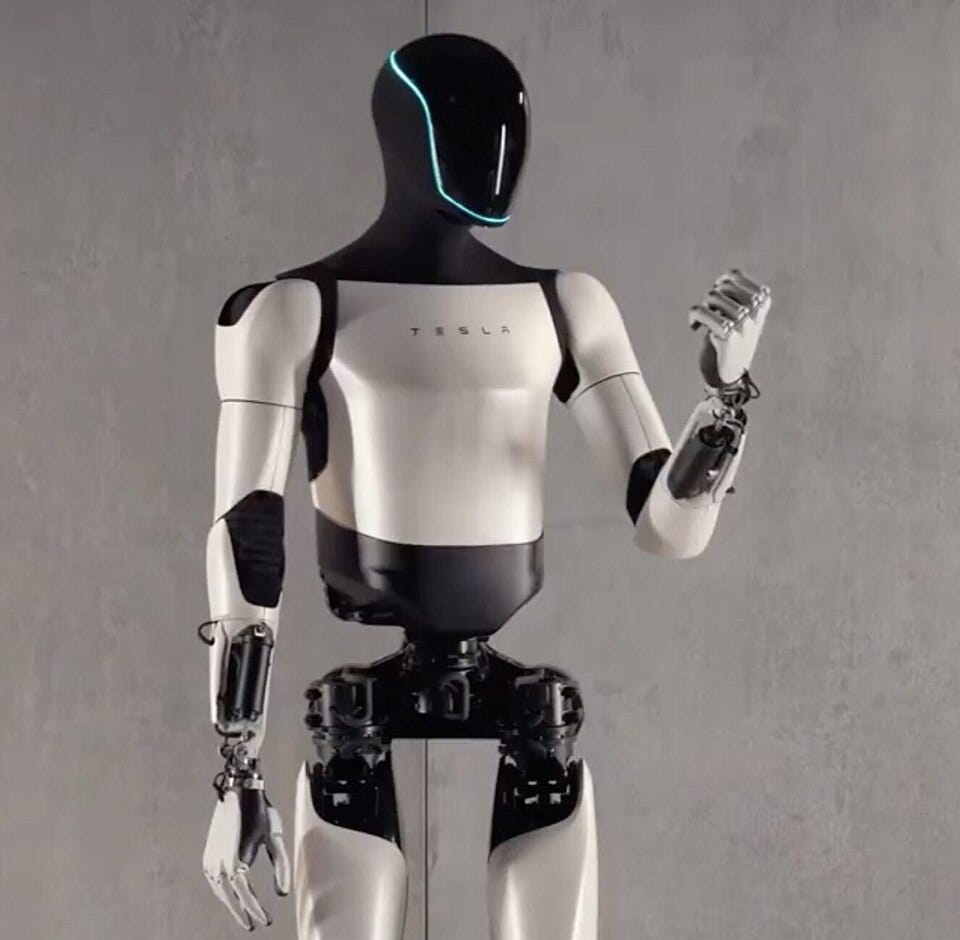

We create systems that learn. We alter life itself. We confront questions that once belonged only to gods. What responsibility does a creator bear once creation begins to act on its own.

When I look across this entire arc, I don’t see religions canceling one another out. I see layers of conscience being added. From belonging, to order, to inner conflict, to restraint, to moral history, to responsibility, to self-governance.

This essay is the first in a series because it frames the problem that never disappears. The world still does not explain itself. The sky remains silent. And the human mind continues to respond the only way it knows how.

By thinking.

By questioning.

By growing.

This essay opens a twelve-part journey I’ll be publishing over the coming weeks, tracing how humanity learned to search for meaning, lost it, reshaped it, and carried it forward. Across these articles, I trace how different cultures and religions wrestled with the same questions — how meaning was discovered, challenged, absorbed into conscience, and carried forward — each tradition adding something essential to the way humanity learned to understand itself.

The fire is still burning.

The questions are still alive.

This is so beautiful and ties everything (cultures, religions, beliefs, mythologies across time) together so effortlessly... wow. I can't wait to read the rest!