The Epigenesis of the Aesthetic Mind

Beauty was Never Meant to be an Afterthought

What if the first moment that shaped your sense of beauty wasn’t a masterpiece, a song, or a sunset but a baby staring at a wandering beam of light, discovering for the first time that the world could be more than a place to survive?

A baby doesn’t know what beauty is. He doesn’t have language or concepts. All he has is attention. Something catches his eye. He locks in. The mother notices, softens her voice, and follows his gaze. Suddenly the world opens into something more than hunger or safety. A small exchange becomes the seed of a new way of relating to reality.

We rarely think of beauty as something foundational. We treat it like decoration. Something we add to life after the hard work is done. But the more you study human behavior, the clearer it becomes: beauty wasn’t an afterthought. It was one of the early forces that taught us how to feel, choose, imagine, and understand.

For centuries, philosophers tried to pin down where our aesthetic sense comes from. Is it built into our biology? Is it passed down like a language? Or does it appear through the way we grow, imitate, and interact with the world?

Kant believed that beauty happens when imagination and intellect fall into a kind of rhythm. He imagined it as a “free play” inside the mind, a moment where your mental faculties sync up and you feel pleasure before you know why. That feeling becomes a signal that the world makes sense in a certain way.

But Kant treated the origin of this experience as almost mechanical, as if it floated above the body. He didn’t consider the pull of desire, the impulses that shape our earliest encounters with the world.

Schiller pushed the conversation further by bringing desire back into the picture. He believed beauty emerges from the way we balance raw feeling with the need for form, order, and coherence. He saw play, not work, not duty, as the birthplace of the aesthetic sense. And once you look at children, this becomes obvious. Every time a child fixes his gaze on something for no reason, he is practicing the early version of aesthetic attention.

This brings us to an unexpected voice in this story: Charles Darwin.

Darwin noticed something strange in the animal world. The most extravagant traits — bright feathers, elaborate dances, absurd displays — often had little to do with survival. In fact, some made survival harder. The peacock’s tail is the classic example. A structure so heavy and conspicuous, it slows the bird down and makes it easier to spot.

If survival were the only goal, this would make no sense. But sexual selection works differently. Beauty becomes a language. Certain traits evolve because they attract, excite, or provoke interest. The female’s ability to notice subtle differences grows sharper. The male’s displays become more dramatic. They co-evolve in a loop of desire and attraction.

This is the first hint that beauty has a life of its own, partly connected to survival, but never reducible to it.

Darwin openly admitted he didn’t fully understand how the “sense of beauty” developed in animals or humans. He knew it wasn’t pure utility. It wasn’t simply a fitness marker. Something else was happening: a drift toward complexity, variation, and pleasure for its own sake.

That drift becomes even more powerful when you reach humans.

At some point in human evolution, desire detached from fixed biological goals. People began wanting things they didn’t need. They were drawn to shapes, colors, rhythms, and faces that had no direct survival value. Desire became indeterminate. It started scanning the environment for new attractors.

And this is where something uniquely human appears. When desire becomes open-ended, it begins to generate its own objects. You learn to find beauty where you once saw nothing. You teach yourself to appreciate patterns you didn’t grow up with. Your taste expands. The world gets richer.

This is how the aesthetic attitude stabilizes. It’s not a single instinct. It’s a habit of attention. Lingering, savoring, selecting, and returning to things that strike you. Over time, this habit becomes part of how you see everything.

To explain how this works, philosophers use the idea of “supervenience.” The word sounds technical, but the meaning is simple. Imagine someone in the prime of life, moving with a certain ease, a natural grace that rests on deeper physical strength. Aristotle saw this as a “bloom” that rests on top of the activity beneath it. Beauty works the same way. Once the structure is in place, a new layer emerges that changes how you experience the whole.

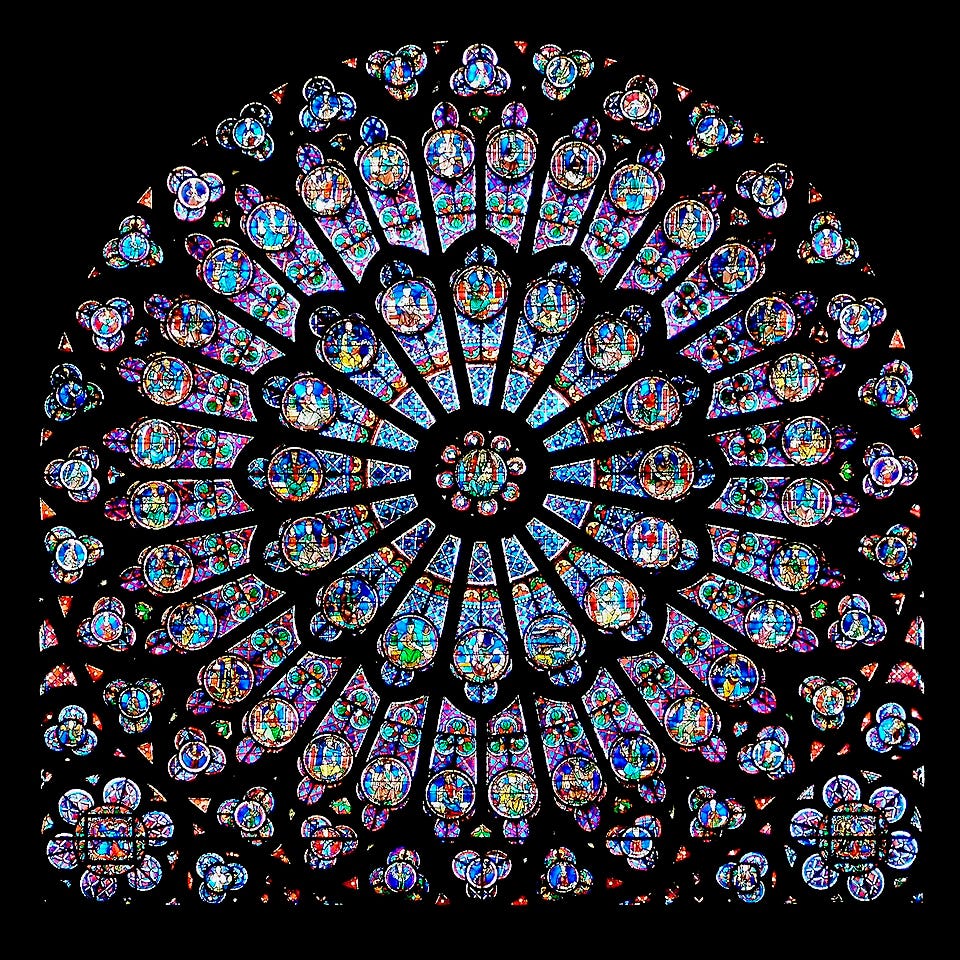

This is why beauty reshapes our world. Aesthetic experience reveals possibilities that weren’t visible through practical reasoning alone. It anticipates meaning before you can articulate it.

Human beings become symbolic animals because, long before we mastered symbols, we responded to patterns, rhythms, and affinities. Beauty gives us a way of sensing the world that prepares the ground for language and culture.

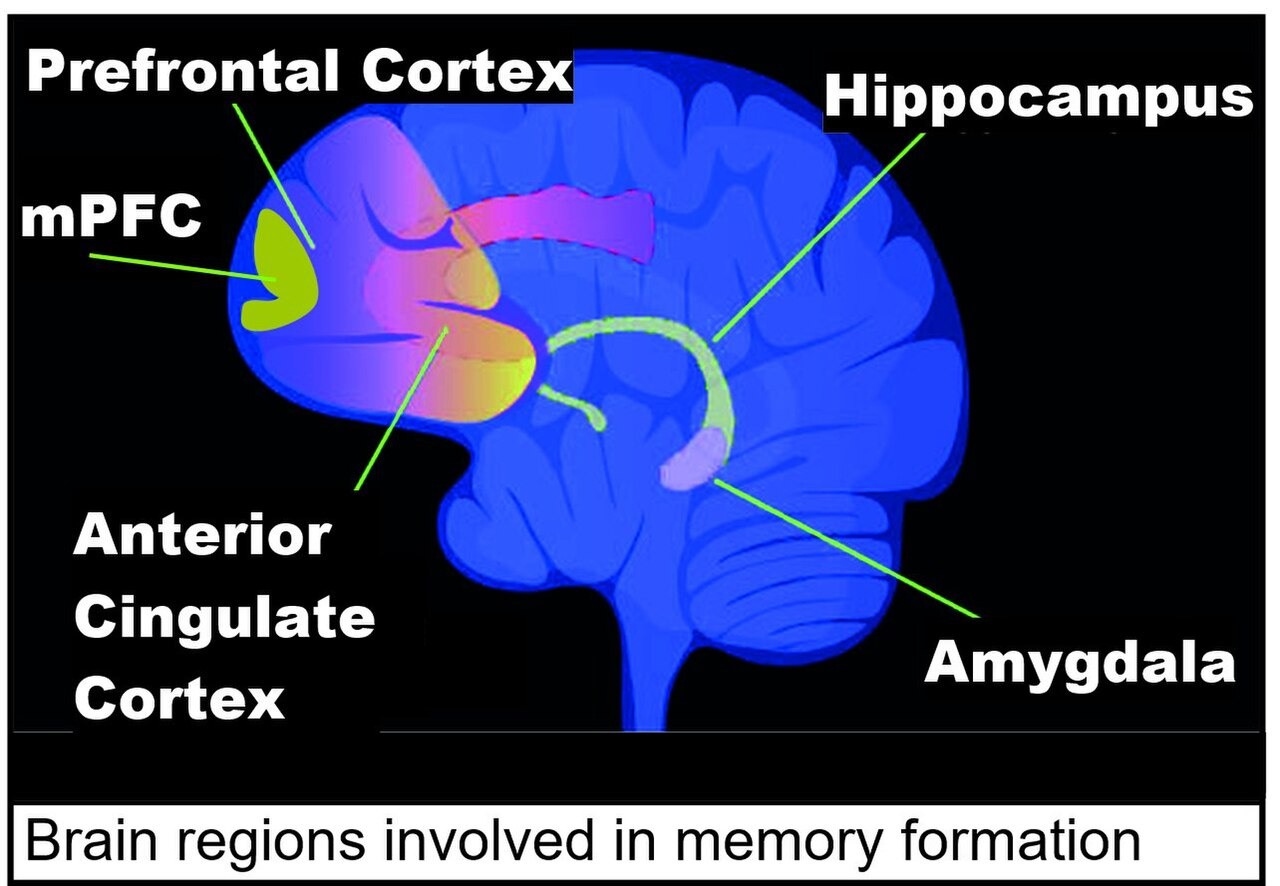

The idea of supervenience also connects to another key concept: epigenesis. Modern neuroscience shows that the brain isn’t a fixed machine. It’s an open network shaped by interaction. Skills, preferences, and habits settle into the brain over time. They aren’t in the genes. They’re in the way experience carves neural pathways.

Aesthetic taste is part of this. The more you engage with music, images, stories, architecture, and landscapes, the more your brain builds flexible templates for recognizing what feels right. These aren’t strict rules. They’re patterns of orientation, ways of seeing meaning in different things.

This explains why your taste evolves. The music you once found chaotic may become meaningful after exposure. A building you once ignored may suddenly feel elegant. Your brain adapts to a richer aesthetic world.

Terrence Deacon, a neuroscientist and anthropologist, takes this further by describing humans as a symbolic species.” He argues that before we have full language, we already treat parts of the world as signs. Shapes, movements, and sounds become meaningful through emotional associations.

Deacon suggests that the aesthetic sense grows out of this early ability to treat things as significant. We start blending feelings with early concepts. When they become more complex, a new cognitive space opens up. That space is the birthplace of art, imagination, and symbolic thought.

At this point, it’s more accurate to talk about an aesthetic device rather than an aesthetic module. A module would be rigid. A device is flexible. It filters, tunes, and amplifies perceptions. It marks certain things as worth paying attention to, even when they’re not directly useful.

This device sits at the boundary between biology and culture. It’s natural in its roots but cultural in its growth. And because it has no single purpose, it becomes one of the most powerful forces in shaping human identity.

Some evolutionary psychologists, like Tooby and Cosmides, argue that beauty must ultimately serve survival goals. They see fictional stories, art, and music as training grounds… safe simulations for emotional learning. There’s insight in that, but something gets lost. Aesthetic experience isn’t just practice for life. It often stands outside utility altogether. It shows that the mind seeks meaning beyond function.

And this brings us back to that baby and the beam of light.

Desideri argues that the aesthetic mind emerges from attention itself. Shared, playful, emotionally charged attention. In early interactions between child and caregiver, the seeds of symbolic life grow out of moments that “don’t need to happen.” They aren’t about survival. They’re about presence, rhythm, and response.

A symbolic mind grows out of an aesthetic mind. Not the other way around.

This means beauty isn’t an ornament on top of human nature. It is part of the way human nature formed. It is an exaptation, a feature that evolved for one thing and then bloomed into something far larger.

Beauty shows us a world where value doesn’t always need a reason. A world where things can be meaningful simply because they resonate with who we are.

And maybe that’s why beauty still matters so much today. In moments when life feels thin or mechanical, beauty reminds us of the part of ourselves that refuses to be reduced to efficiency or utility. It reminds us that attention can be an act of love. That pleasure can be a guide. That meaning can appear in the simplest places.

Even in a wandering patch of light watched by a child and a mother who paused long enough to notice.

Utility without beauty is vain. We have seen it in engineering.

This is so good… And you know what I believe I believe it was woven into us because we were made in the likeness of God, and therefore we are creators and creators without this sense of beauty is mechanical…