The Forgotten Cinderella of the South Seas

Stories are Maps of How People See the World

Before Cinderella wore glass slippers, a girl in ninth-century China mourned a dead fish and changed the course of world storytelling.

Her name was Yexian.

She wasn’t European.

And her story might be the most complete early Cinderella we have, yet almost no one outside China knows it exists.

We’re taught that Cinderella is a European fairy tale shaped by Charles Perrault, polished by the Brothers Grimm, and brought to life by Disney.

But centuries earlier, in the Tang Dynasty, a Zhuang storyteller in southern China told a version that had almost every element we know today: the cruel stepmother, the festival, the lost shoe, the recognition, the marriage.

And also… something the Western versions erased.

A red goldfish.

An ancestor spirit.

A political warning.

The Story

Yexian’s mother dies young. Her father, a tribal chief, takes another wife. When he too dies, Yexian is left with her stepmother and stepsister, who send her to fetch water from deep wells and gather wood on dangerous cliffs.

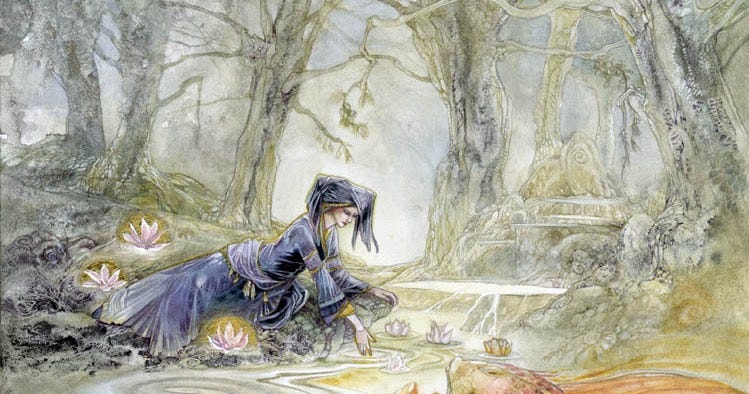

One day, she finds a fish in her bucket—small, strange, with a red fin and golden eyes. She keeps it in a bowl, feeds it scraps, and watches it grow. When it outgrows the bowl, she releases it into the pond behind her home. It greets her every time she comes, resting its head on the bank.

Her stepmother kills it. Eats it.

Grieving, Yexian wanders into the wilderness. There, a being from the sky—genderless, hair unbound—tells her the fish’s bones still hold power. She retrieves them from the trash and hides them in her room. When she prays to them, they grant her gifts: a sky-blue cloak, slippers light as down, beauty that reveals her true self.

When the Zhuang festival comes—a day where women could openly choose their husbands—Yexian goes in secret. She turns every head.

But she leaves before she’s found out, losing one slipper along the way.

It ends up in the hands of a king from across the southern seas. He sends word across the land to find the woman who can wear it.

It fits Yexian.

He marries her.

Her stepmother and stepsister die under a rain of stones.

But this isn’t “happily ever after.”

The king grows greedy. He hoards the fishbones with gold and pearls. When soldiers rebel, he tries to use this treasure to pay them. The tide rises and sweeps it all away.

It’s a warning: misuse what is sacred, and you will lose it.

Why It Matters

Yexian’s story isn’t just a fairy tale.

It encodes the history, beliefs, and skills of the Zhuang people—an ethnic group in southern China who resisted imperial rule for centuries.

The blue cloak may reference plant dyes unique to their region.

The slippers connect to Zhuang courtship customs, where women gifted handmade shoes to men they favored.

The fish mirrors Tang-era innovations in red carp aquaculture—an agricultural breakthrough in Guangxi.

Even the ending has political bite: it warns against corruption, greed, and the exploitation of gifts meant for good.

Rhodopis: The “Older” Cinderella

Yes, there’s an earlier written version: the story of Rhodopis, recorded by Greek geographer Strabo in the first century BCE.

Rhodopis was a Greek slave in Egypt. An eagle stole one of her sandals and dropped it into the Pharaoh’s lap. He searched for the owner, found her, and made her queen.

“They tell the fabulous story that, when she was bathing, an eagle snatched one of her sandals from her maid and carried it to Memphis; and while the king was administering justice in the open air, the eagle, when it arrived above his head, flung the sandal into his lap; and the king, stirred both by the beautiful shape of the sandal and by the strangeness of the occurrence, sent men in all directions into the country in quest of the woman who wore the sandal; and when she was found in the city of Naucratis, she was brought up to Memphis and became the wife of the king.”

It has the shoe, the lowly woman, the royal marriage, but no stepmother, no magical aid, no layered cultural meaning. The bird, identified as an eagle, was also not known in Egypt, creating discrepancies in the story.

Rhodopis is older in writing. Yexian is richer in form.

The Real Legacy

Western versions trimmed Yexian’s story down to romance. The Zhuang version is about survival.

It says beauty is revealed, not bestowed.

It says kindness and skill can lift the lowly.

It warns that greed will be washed away like treasure beneath the tide.

Yexian matters because it reminds us that stories aren’t just entertainment, they are maps of how a people see the world.

And in this map, drawn more than a thousand years ago, a Zhuang girl still walks to the water’s edge, a red goldfish rising to greet her.

The Journey of Yexian’s Story

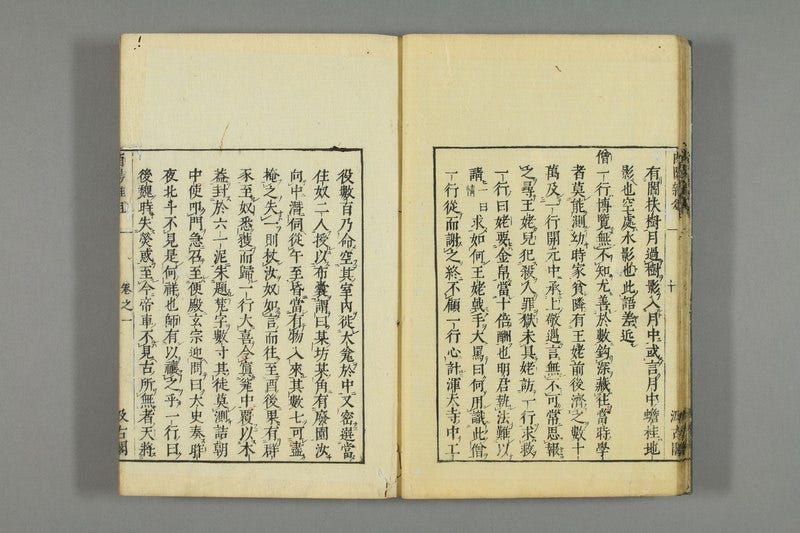

The written source for Yexian’s tale is Youyang Zazu (酉阳杂俎), compiled around 850 CE by Duan Chengshi, a Tang Dynasty official.

Duan lived in Nanning for nearly three decades, deep in Zhuang territory. His informant for the story, Li Shiyuan, was Zhuang himself. In the text, Duan calls him a “cave-dweller” from Yongzhou, a term that, in Tang administrative language, marked him as part of a recognized ethnic group, not a literal inhabitant of caves.

Why this matters: Duan’s Youyang Zazu wasn’t a fairy tale book. It was a miscellany, part ethnography, part strange tales, part court gossip. That makes Yexian’s inclusion remarkable. It wasn’t framed as a child’s tale, but as a cultural record worth preserving alongside imperial anecdotes and geographic lore.

How Could It Have Reached Europe?

We don’t have a neat chain of custody. But we do have clues.

By the 16th century, Youyang Zazu was still in print and circulating in China. At the same time, Chinese ports were trading with Portuguese, Spanish, and later Italian merchants. Jesuit missionaries, fluent in Chinese, were active in the Ming court. These were the same routes that carried silk, porcelain, and mathematical texts westward.

Italy, especially Venice and Naples, was the entry point for much of this traffic. The first major European fairy tale collections appear in Italy: Le Piacevoli Notti by Straparola (c. 1550) and Il Pentamerone by Basile (1634). It’s not impossible that motifs from Yexian arrived by ship, reshaped by oral retelling before being written down in European form.

Why the Ending Matters

Western versions drop the final scene of Yexian’s story, the king losing his hoarded wealth to the tide.

But in Zhuang historical context, it makes sense. In the Tang era, Guangxi had been drawn into the imperial tax system. Gold and pearls flowed north; rebellion followed. The ending may be a veiled commentary: wealth taken without honor will vanish, just as the tide erases footprints in sand.

Final Thought for Subscribers

If we only look at written dates, we give the “oldest Cinderella” title to Rhodopis. But if we look at narrative completeness, cultural symbolism, and moral depth, Yexian is unmatched.

It’s the version that still speaks to survival under empire, the value of skill, and the danger of greed, lessons that feel as relevant now as they did on the banks of the Li River over a thousand years ago.

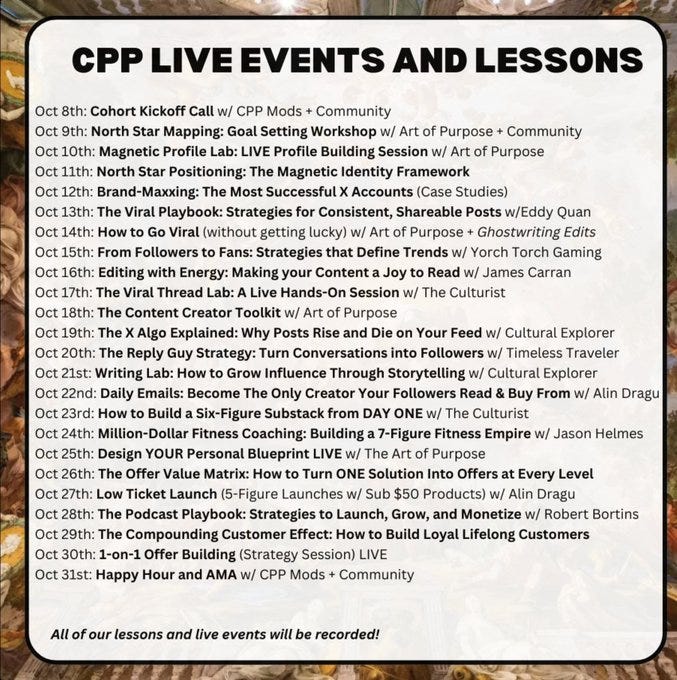

CPP - A Workshop for Content Creators

At the start of 2024, I was stuck at 4K followers and $0 online income. Now I’m at 152K and making $3K+ a month from my content. The shift came from one program. Art Of Purpose (@creation247) is offering CPP again starting October 8th.

Joining Create, Publish, Profit changed everything. The difference wasn’t just theory, it was the stack of hands-on workshops that covered everything: how to build a magnetic profile, write viral threads, grow with storytelling, design offers, even launch a Substack or podcast from scratch. Every lesson was practical, backed by people who’d already done it.

Interesting. Love reading other "versions" of fairy stories. The red goldfish in Yexian’s story is unique. It seems to embody the ancient symbolism of fish as living sparks hidden in chaotic waters.

In Scripture and early Christian art, fish represented nourishment drawn from the waters of death. The ichthys became a sign that life could be found where death seemed to reign.

Water carries the sense of chaos and potential death, but fishing signifies pulling from that abyss what is precious and sustaining. Yexian’s fish, shimmering with gold and red, is such a shining principle of order emerging from chaos. Even when killed, its bones continue to mediate life, like relics.