The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (1204)

How the Cross Turned Against Its Own

People still ask how it happened. How the greatest Christian city in the world, the “New Rome” that had withstood Persians, Arabs, and Turks, fell not to Islam, but to the armies of the cross. How a crusade meant for Jerusalem ended in the looting of Constantinople. And how the guardians of Christendom became its executioners.

The Fourth Crusade remains one of history’s great paradoxes: a holy war that lost its purpose before anyone drew the first sword. It was a mission born in faith, undone by debt, and remembered as one of Christianity’s darkest hours. What began as a call to reclaim the Holy Land ended with flames rising over the Hagia Sophia and monks slaughtered at their own altars.

No war began with purer words and ended in greater shame than the Fourth Crusade. It was meant to reclaim the Holy Land. Instead, it destroyed the greatest Christian city on earth. The Crusaders set out to fight Muslims and ended up looting churches filled with relics of Christ. Even today, fragments of that plunder glitter quietly in cathedrals across Europe, a memory of faith corrupted by greed.

It began, as most disasters do, with high ideals and misplaced trust. At the dawn of the 13th century, Pope Innocent III called for a new crusade to restore Jerusalem, lost once again to Muslim forces. His vision was pure, a united Christendom marching east to reclaim the holy sites. But the crusaders he inspired were not monks or mystics; they were princes, soldiers, and debtors.

To reach the Holy Land, they needed ships. Venice offered them. And in that agreement, the first crack in their holy purpose, fate turned.

The Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, was an old man, blind but cunning, a merchant before he was a crusader. Venice agreed to build a massive fleet, enough to carry 30,000 men to Egypt, the proposed target. But when the crusaders arrived in 1202, they couldn’t pay.

Venice had spent fortunes building the ships. The crusaders were out of money, so the Doge offered a compromise that would change the course of history. He proposed that they could have their debt forgiven if they helped Venice capture the rebel Christian city of Zara. Zara wasn’t Muslim. It was Catholic. The Pope forbade the attack. The crusaders went anyway.

They took Zara, sacked it, and for the first time spilled Christian blood under the banner of the cross. The Pope excommunicated them all. Still, the army pressed on—lost, leaderless, and already stained by its first sin.

Then came another twist. A young Byzantine prince, Alexios Angelos, arrived at their camp. In Constantinople, his father, Isaac II, had been deposed and blinded. The boy promised the crusaders a fortune, ships, and soldiers if they helped him reclaim his throne. All he wanted, he said, was to restore his father. All they wanted was gold.

So, the crusaders redirected their path from Jerusalem to Constantinople, which was known as New Rome, the jewel of Christendom, a city that had never experienced breaches to its spires and domes.

When their ships appeared on the horizon in the summer of 1203, the citizens watched in disbelief. A Christian armada was bearing down on them.

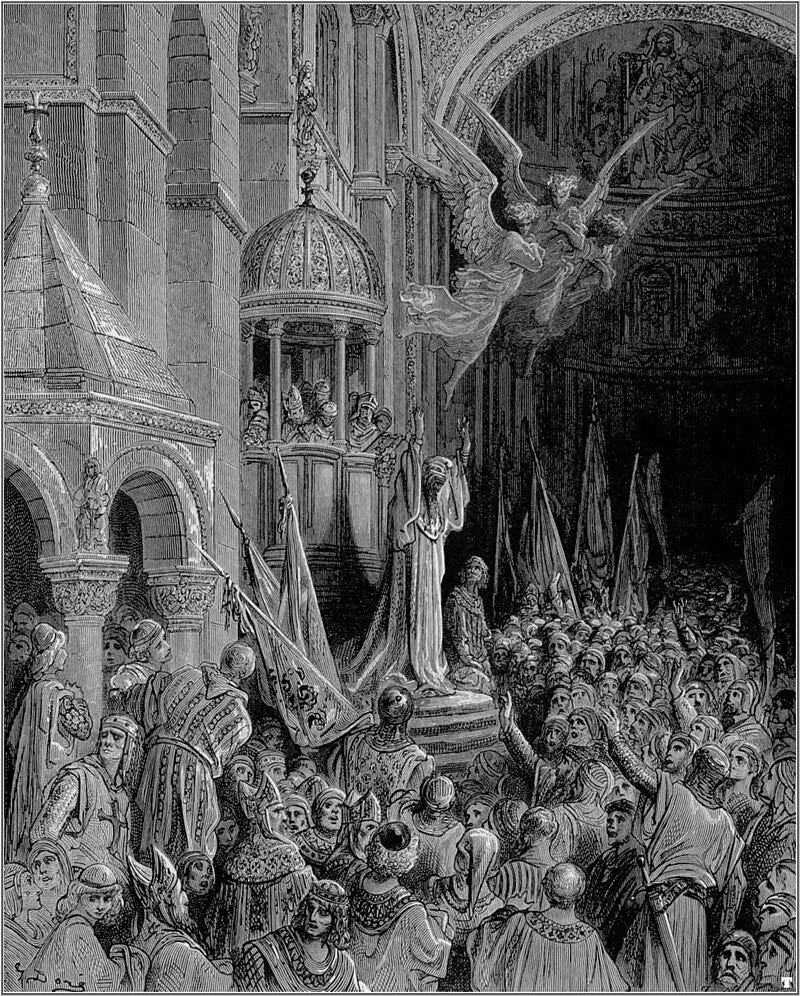

The crusaders attacked the walls by sea while the Venetians stormed them by land. The sight of the blind Doge standing on the prow of his ship, carrying the banner of St. Mark into battle, became legend. Defenders at Constantinople faltered. Emperor Alexios III fled. The boy prince entered the city in triumph, restored his father, and paid the mercenaries at least for a while.

But Constantinople was not a city that forgot. Its people despised the Latin soldiers who filled its streets, boasting of conquest and demanding payment. The treasury ran dry. The new emperor, Alexios IV, couldn’t keep his promises. He melted church treasures, stripped icons of gold, and taxed the citizens to feed his crusader “allies.” Hatred grew like fire under ash.

In January 1204, the city erupted. The Greeks rose against the Latins. Fires spread through its markets and murdered the emperor while asleep. The crusaders, furious and unpaid, turned from holy war to vengeance.

On April 12, 1204, they attacked. For three days, Constantinople burned.

The crusaders smashed through the gates, looting the city street by street and slaughtering the monks before their altars. The crusaders stripped Hagia Sophia, the grandest church in the world, bare. Horses drank from its marble baptistery. They set a prostitute on the Patriarch’s throne to mock the faith they claimed to defend.

They tore relics from shrines — the Crown of Thorns, the True Cross, the Virgin’s veil — and shipped them west. Many still sit in the basilicas of Venice, Paris, and Bruges. The bronze horses that crown St. Mark’s Basilica once stood over the Hippodrome of Constantinople. They are trophies of betrayal.

When the flames died, the greatest Christian city in the world lay in ruins. Its libraries, containing the last manuscripts of Greece and Rome, were burned and its churches gutted. Its people enslaved.

The Latin conquerors carved the empire into pieces like merchants dividing spoils. Baldwin of Flanders became emperor of a “Latin” Constantinople. Venice claimed the harbors, the islands, and the trade routes.

The Pope condemned the sack but accepted the reality. A Latin patriarch replaced the Greek one. The Eastern and Western churches, already estranged since 1054, were now enemies in blood. The schism hardened into permanence.

Byzantium never recovered its strength. Though the Greeks retook the city in 1261, the old power was gone. The empire limped on for two centuries, weakened, divided, and ripe for conquest. When the Ottomans finally captured Constantinople in 1453, they found an exhausted city, its fall made inevitable by Christians who had torn it apart 250 years earlier.

And what of the crusaders? They went home rich, cursed, and damned by history. Their relics became church treasures, their gold built cathedrals, and their sins built legends. The Fourth Crusade never saw Jerusalem. It killed the city that had stood for a thousand years as Christianity’s bulwark against the East.

The aftermath reshaped the world. Venice rose as a maritime empire, its wealth built on plundered marble and stolen relics. The Byzantine refugees fled west, carrying with them manuscripts and learning that helped spark the Renaissance. The fall of Constantinople to the Christians in 1204 was the beginning of its fall to the Muslims in 1453.

Historians later called it “the first great blunder of the West in dealing with the East.” They were right. By destroying Constantinople, the West destroyed the shield that had kept Islam from entering Europe.

The lessons are old but eternal. Faith without discipline becomes zealotry. Idealism without honesty becomes greed. And when men use God to justify ambition, they build their own downfall brick by brick.

The Fourth Crusade began with prayers and ended with smoke. It showed that betrayal by those who were supposed to defend it could cause a civilization to collapse. The sack of Constantinople was not just a medieval tragedy. It was a warning that even a holy cause can be lost when its defenders lose their souls.

🔒 Premium Section — The Relics That Still Bear the Scars of 1204

For paying members, I’ve compiled a guide tracing 10 surviving relics and treasures from the 1204 sack, each still housed in Western Europe today. You’ll see where they ended up, how they were smuggled out of Constantinople, and what traces of the old empire can be seen through them.

Among them:

The Bronze Horses of the Hippodrome, now crowning St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

The Pala d’Oro, crafted from Byzantine enamels, once the altar screen of Hagia Sophia.

The Crown of Thorns, later purchased by King Louis IX, now enshrined in Sainte-Chapelle, Paris.

The Virgin’s Veil in Chartres, brought by crusaders who claimed to have rescued it from looters.

And a fragment of the True Cross, quietly displayed in the treasury of Bruges Cathedral.

Each object tells part of the story of 1204… not only of destruction, but of how beauty survives even in defeat.