The Good Emperor, The Dangerous Emperor ...

In a world commanded by tradition, one extraordinary Emperor dared to be different...

Some emperors conquer with blood. Others with silence.

This week’s edition takes you deep into China’s imperial past. Two new essays trace the shape of power, one by Endless Days of Summer, the other by Culture Explorer—through the unexpected forms it can take: restraint and stone.

Endless Days of Summer begins with a boy hidden in the shadows of the Forbidden City. In The Good Emperor, the Dangerous Emperor, we follow the rise of Zhu Youcheng, the kind Ming sovereign who refused to be like his predecessors.

Culture Explorer then turns to a very different ruler: China’s First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang. His Terracotta Army was not a symbol of restraint, but of eternal command, a silent legion crafted to serve him in the next world.

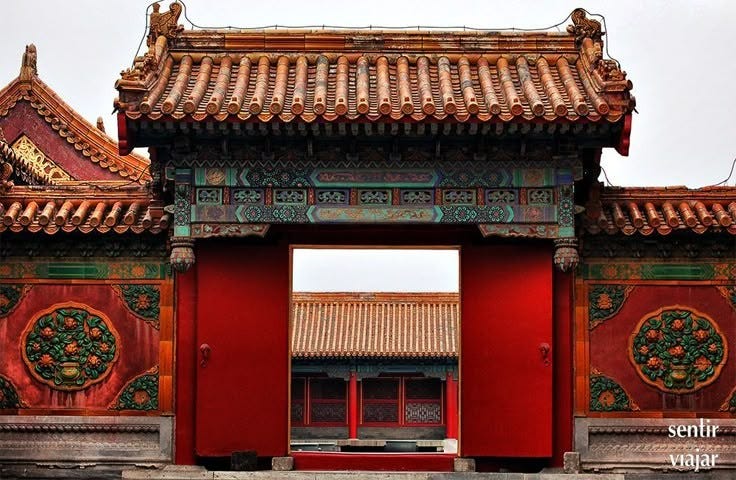

Together, these two pieces offer a double portrait of power: one soft, one unyielding. Both unforgettable. We wrap up the newsletter with a look at the haunting beauty of The Nymph of the Luo River, architectural symbolism of the Forbidden City, and the unyielding force of the Great Wall of China.

The Good Emperor, The Dangerous Emperor...

By Endless Days of Summer

The child grew within her in silence. And that silence became a matter of life and death.

In the vast, echoing corridors of the Forbidden City, power walked in silence and in shadows. While emperors ruled in lacquered halls and concubines maneuvered through veils of silk and suspicion, a secret trembled behind the palace walls. In 1470, a woman of no title, no favor, and no known power gave birth in the cold recesses of the inner court. Her name was Lady Ji.

She was not one of the grand favorites. No history of elegance or warlike ambition crowned her lineage. She was simply a palace servant, likely a Yao woman captured during the suppression of the rebellion in the province of Guangxi—meek, kind, and entirely forgettable to most. But not to the Emperor.

Emperor Chenghua, weary from the brutal machinery of his own court, saw in her a kind of gentleness that was scarce and unsought. Whether he loved her or simply found momentary peace in her presence, no one could say. But he lingered. And from that quiet liaison, a son was born.