The Kingdom Within Is Real

Article 10 of Arc of Belief and Meaning Series

I was listening to a Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan qawwali when it happened.

I had heard of people slipping into a trance while listening to him, so I wasn’t listening casually. I was sitting there, fully locked in, letting the qawwali run its course the way it’s meant to. The harmonium opened the space like a gate. The clapping began, steady as a heartbeat. Then Nusrat’s voice entered, and it felt like force, like something pushing against the walls of my mind until they started to crack.

At first, I was hearing music. Then I started hearing something else.

The repetition kept coming back, again and again, the same lines circling like a blade. It wasn’t repetition for decoration. It was repetition with intent. It felt like the song was doing something to me, not entertaining me. Slowly, almost without permission, the part of my mind that always wants to interpret, judge, analyze, translate, and label began to weaken. The inner commentary thinned out. The noise inside my head started losing its grip.

And then, for a moment, it happened.

Stillness.

Not silence in the room. Silence inside me. The kind of silence that feels alive, not empty. Like you’ve stepped behind the curtain of your own thoughts and discovered something that has been there the whole time.

I remember sitting there thinking this is what they mean.

Not superstition. Not vague spirituality. Not poetic exaggeration. This is what mystics are pointing to. The discovery that the mind is not the center of you. That beneath craving, beneath identity, beneath constant thought, there is something quieter, deeper, almost frighteningly steady.

And what shocked me most was that this realization didn’t come through philosophy.

It came through devotion.

It came through a Sufi singer pouring out the names of God with such intensity that it felt like the ego couldn’t survive the heat. Like the self had to step aside.

That moment didn’t make me religious overnight. But it did something more dangerous. It made me curious. Because if Nusrat could pull me into that kind of inner stillness through Islamic devotional music, then what else had human beings discovered across history? What had monks in deserts found? What had saints seen? What had yogis mastered? What had Buddhist monks been sitting in silence for centuries trying to reach?

That night didn’t feel like listening to music. It felt like stumbling onto a hidden door. And once you’ve seen the door, you can’t pretend it isn’t there.

Sufism, at its core, is built around this exact idea. It is often described as the inner dimension of Islam, the attempt to move from outward submission to inward transformation. Classical Islamic spirituality speaks of Islam, Iman, and Ihsan: outward obedience, inward faith, and then the highest stage, where worship becomes so vivid it is like direct sight. A famous hadith captures it with terrifying clarity: “Ihsan is to adore Allah as though thou do see Him, for even if thou do not see Him, He nonetheless sees thee.” That is the description of a mind that has been trained into awareness.

Sufis believed the main obstacle to this awareness was the nafs, the lower self. Not the body itself, but the ego that clings to pleasure, recognition, status, and control. The nafs turns even religion into vanity. It can make a man proud of his prayer, arrogant in his morality, obsessed with being seen as holy. That is why so much Sufi discipline is aimed at stripping the self of its hidden addictions.

Dhikr, the remembrance of God, became one of the most central tools. To an outsider, dhikr can look like chanting. But the Sufi understands it as inner warfare. Repetition is used to exhaust the mind’s restlessness. The heart is polished through remembrance until it begins to perceive what the mind cannot. This is why qawwali fits so naturally into Sufism. It is not entertainment. It is dhikr set on fire. It builds and builds until the listener feels exposed, as if the ego is being forced into retreat.

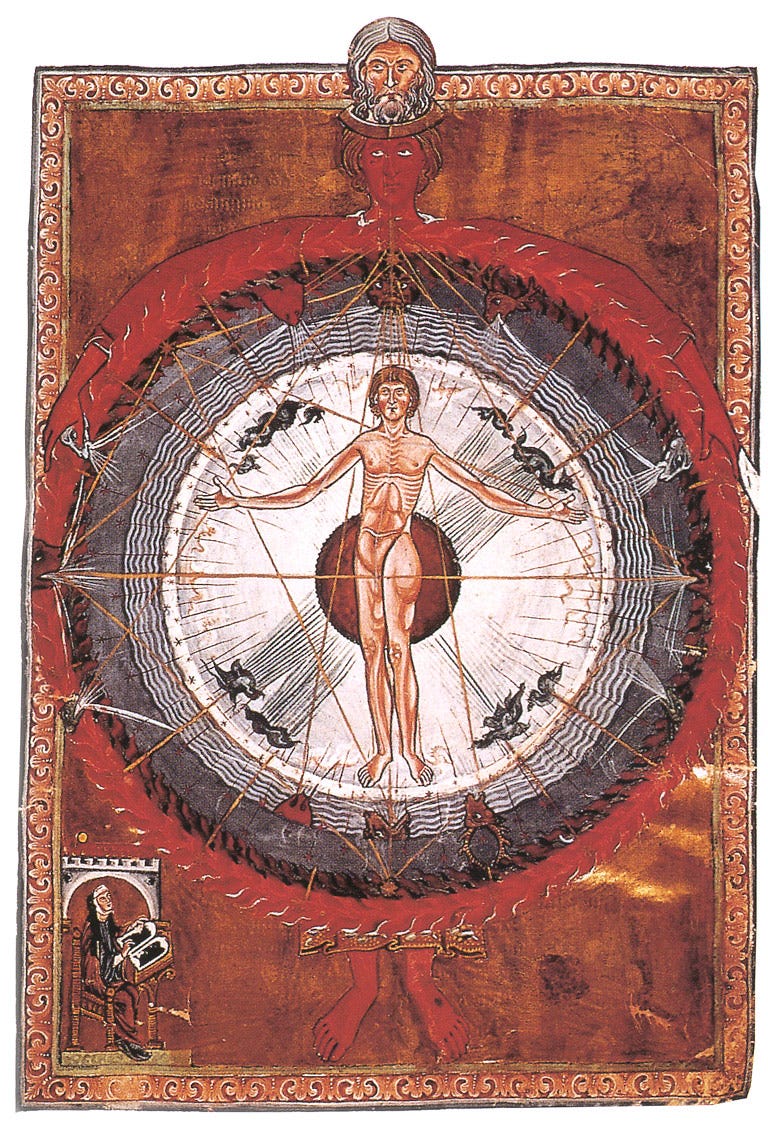

The mystic’s goal was never simply emotion. The goal was reality. Some Sufis spoke of tawhid, the unity of God, not as a doctrine but as a lived unveiling. This is why the most radical Sufi concept is fanā, the annihilation of the ego-self. It means the collapse of the illusion that you are the center of the universe. And from that collapse comes baqā, abiding in God, a life lived with the ego dethroned.

The Islamic world produced many scholars, but it also produced men who walked away from prestige because knowledge alone did not satisfy the soul. One of the most famous examples is Abu Hamid al-Ghazali. He was a celebrated scholar in Baghdad, admired for his intellect, influence, and teaching. Yet he experienced a spiritual crisis so severe that his voice failed him. He could not speak. He abandoned his career and disappeared into solitude, later describing how certainty cannot be achieved by argument alone. It must be tasted. It must be lived. That is the mystic’s rebellion against the pride of intellect.

Christianity, despite its very different theology, developed an inward path that mirrors this almost perfectly. In the fourth century, as Christianity gained legitimacy in the Roman Empire, thousands of Christians did something shocking. They fled civilization. They went into deserts, mountains, caves, and wilderness, leaving behind cities, wealth, and ordinary social life. These were the Desert Fathers, and they were trying to escape distraction.

The desert was not symbolic. It was heat, hunger, isolation, and fear. But the monks believed the desert revealed the truth about the human mind. Remove society’s noise and you begin to see what is actually inside you: lust, rage, despair, pride, fantasies, self-pity. The monks spoke openly about the mind as a battlefield. Their temptations were not only physical. They were mental. They fought what they called destructive thoughts, patterns that attacked the soul from within. In modern terms, they were describing intrusive thoughts and obsessive compulsions centuries before psychology existed as a discipline.

And this wasn’t a fringe movement. Archaeological evidence from the Holy Land reveals how widespread monastic life became. Hundreds of monastic sites have been identified from the fourth to early seventh centuries. In the Judean Desert alone, over sixty monasteries have been found, not even counting the countless caves used as hermitages. Entire landscapes were shaped by men who chose silence as their vocation.

Many monks were drawn to locations connected to Biblical memory. Sinai mattered because of Moses. St. Catherine’s Monastery was built on the site associated with the Burning Bush. The monk was not merely seeking emptiness. He was seeking sacred geography. He wanted to live inside scripture, not just read it.

From this desert tradition came practices like hesychasm, especially strong in Eastern Christianity. Hesychasm means stillness. Its famous tool was the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” Repeated quietly, sometimes coordinated with breathing, it was meant to descend from the lips into the heart. The goal was purification. The monk believed the heart was the seat of perception, and that only a purified heart could see reality as it truly is.

Christianity also produced saints, and saints were not treated as sentimental moral mascots. In medieval Europe, saints were central to the lived religious imagination. They were called friends of God and soldiers of Christ. People believed saints could cure sickness, drive out demons, stop fires, protect cities, counter famine, and even defeat enemies. Their power was believed to increase after death, because they now dwelled in the divine court and could petition God directly on behalf of the living.

This belief reshaped Christian civilization. Shrines became pilgrimage destinations. Relics became treasures. People traveled to bones, tombs, garments, and holy sites not as tourists, but as supplicants. The saint was not merely admired. The saint was invoked. There was no better ally, medieval Christians believed, than someone already in heaven when the final judgment arrived.

The language itself reveals how they thought. The Latin word virtus meant both moral virtue and miraculous power. In other words, holiness was not private. Holiness was force. The saint’s interior transformation was believed to spill outward into reality, like heat from a fire. And Augustine of Hippo clarified something crucial: Christians were not worshipping saints as gods. They honored them, but worship belonged to God alone. “The martyrs have their place of honor,” Augustine said, “but they are not adored in the place of Christ.” Saints were meant to be witnesses, proof that a human being could become something radiant.

After reading about saints and monks for years, what struck me most was not the miracles. It was the consistency. Whether it was a hermit in the desert, a saint living in poverty, or a monk repeating a prayer thousands of times, the logic was the same: the mind must be conquered. The ego must be dethroned. The kingdom of God is not first built in the world. It is built inside the person.

And this is where yoga entered my life in a way that surprised me.

I had always associated yoga with stretching, wellness culture, and calming background music. I assumed it was physical. Maybe therapeutic. But the first time I tried yoga seriously, I realized almost immediately that the body was not the real problem. The body complains, yes, but the body is honest. It aches, it tightens, it resists, but it also obeys with practice.

The mind is different.

Within minutes of stillness, I felt the mind revolt. It started negotiating. It started producing excuses. It began dragging up memories I hadn’t thought about in years. It kept jumping forward into tomorrow, then backward into regret. It wanted stimulation the way an addict wants a hit. The more I tried to hold the posture and breathe steadily, the more I realized something uncomfortable: I was not controlling my own consciousness. I was being pulled around by it.

That was the shock. Yoga didn’t feel like exercise. It felt like confrontation.

It was like stepping into a quiet room and suddenly hearing how loud your mind really is. The thoughts weren’t profound. They were repetitive, childish, restless. The urge to check my phone. The urge to stop. The urge to do something else. And underneath that urge, something deeper: a fear of being alone with myself. That fear explained why yogic traditions were never casual hobbies. They were systems of discipline designed to tame the mind.

Traditional yoga was never just about flexibility. It was about liberation. Some yogic practices were so intense they sound almost unreal. Certain techniques involved breath control so precise it was treated like spiritual engineering. Others involved bodily austerities meant to break attachment to comfort. Some yogic sects marked themselves physically. The Nāth yogis, for example, were called “split-eared” because holes were cut into their ear cartilage where they wore large hoop earrings. Their appearance was a declaration that they belonged to a different world.

Some techniques went even further. Khecarīmudrā involved loosening and lengthening the tongue so it could be turned back into the cavity above the palate. Yogic texts claimed this allowed access to amṛta, the “nectar of immortality” said to drip from the crown of the skull. Whether one believes the metaphysics or not, the psychological meaning is clear: these were people who treated the inner world as something real enough to be pursued with pain, secrecy, and obsession.

And then Buddhism takes the same map and strips it down to its bare bones. Buddhism begins with a man who had everything and found it meaningless. Siddhartha Gautama was born into privilege, sheltered from sickness, aging, and death. When he finally encountered those realities, his worldview shattered. He left his palace and pursued truth with ruthless honesty. His conclusion was simple and terrifying: craving creates suffering. Not only craving for pleasure, but craving for permanence, craving for identity, craving for control.

Buddhist monks turned that insight into disciplined practice. Meditation in Buddhism is not relaxation. It is training in perception. The monk sits, watches the mind arise and fall, and gradually sees how thoughts manufacture the illusion of a stable self. This is why Buddhist silence can feel sharp. It is not sentimental. It is surgical.

Zen Buddhism expresses this with brutal simplicity. A student asks, “What is the Buddha?” The master replies, “Three pounds of flax.” The answer is meant to collapse the mind’s addiction to abstraction. Reality is not an idea. Reality is immediate. The monk trains himself to stop living in narratives and return to what is.

Step back and the pattern becomes hard to ignore. Sufis, monks, saints, yogis, and Buddhist renunciants all end up describing the same inner enemy: the ego, the restless self that craves attention, control, and reassurance, and that fills every quiet moment with noise. They may disagree on theology, but they agree on this much: most human suffering is not caused by the world alone, but by the mind’s inability to stop grasping.

What’s even more striking is that they converge on the same solution. Whether it is dhikr, the Jesus Prayer, mantra, fasting, solitude, or meditation, the goal is always similar. They use discipline to wear down the mind’s constant chatter until a deeper awareness breaks through. The methods look different from the outside, but the psychological logic is nearly identical: repetition steadies the mind, solitude exposes what distraction hides, and self-denial weakens the tyranny of appetite.

And when they describe what lies on the other side, their language begins to overlap. They speak of stillness, clarity, presence, and a strange interior freedom, as if the self you thought you were is only a surface layer. The Sufi calls it worship as if seeing God. The Christian calls it purification of the heart. The yogi calls it liberation from illusion. The Buddhist calls it awakening. But beneath those names is the same experience: the false self loosens its grip, and something steadier takes its place.

That is why mysticism was not seen as harmless, rather it was quietly revolutionary. If the kingdom is within, then the outer world cannot fully own you. Not status, not propaganda, not fear, and not even death. A person who has found that interior center becomes difficult to manipulate, because he no longer needs constant validation from the crowd.

And maybe that is why modern life feels so hollow. We have conquered the external world with machines, medicine, and endless entertainment, yet we are increasingly homeless inside ourselves. We drown in noise because silence forces us to face what we’ve avoided.

So here’s the question that should unsettle us: if every civilization’s greatest seekers found the same stillness at the center of the soul, why does modern man spend his entire life running from it?

And maybe that is the real reason mysticism keeps returning across history. Not because people were bored, but because sooner or later every culture realizes the same thing: the outer world can be conquered, but it cannot satisfy. The deeper hunger is inside.

In the next article, I’m going to follow that hunger to its final frontier: what civilizations believed happens when the world itself reaches its breaking point. The article will explore Revelation, Ragnarök, and the Yugas, and why humanity has always imagined judgment and rebirth at the edge of time.

If you want the next piece when it drops, subscribe and read it from your inbox.

This is a stunningly beautiful essay! I felt your inner transformation and joy. You explain the commonality of meditative practices across religions better than any other read/spoken descriptions I’ve known before. And your writing is sheer poetry. So many magnificent, memorable lines! Enjoying this series. Thank you!

Intriguing, enlightening, and unexpectedly relaxing.