The Lost Religion of Architecture

The Moment Beauty Became a Function

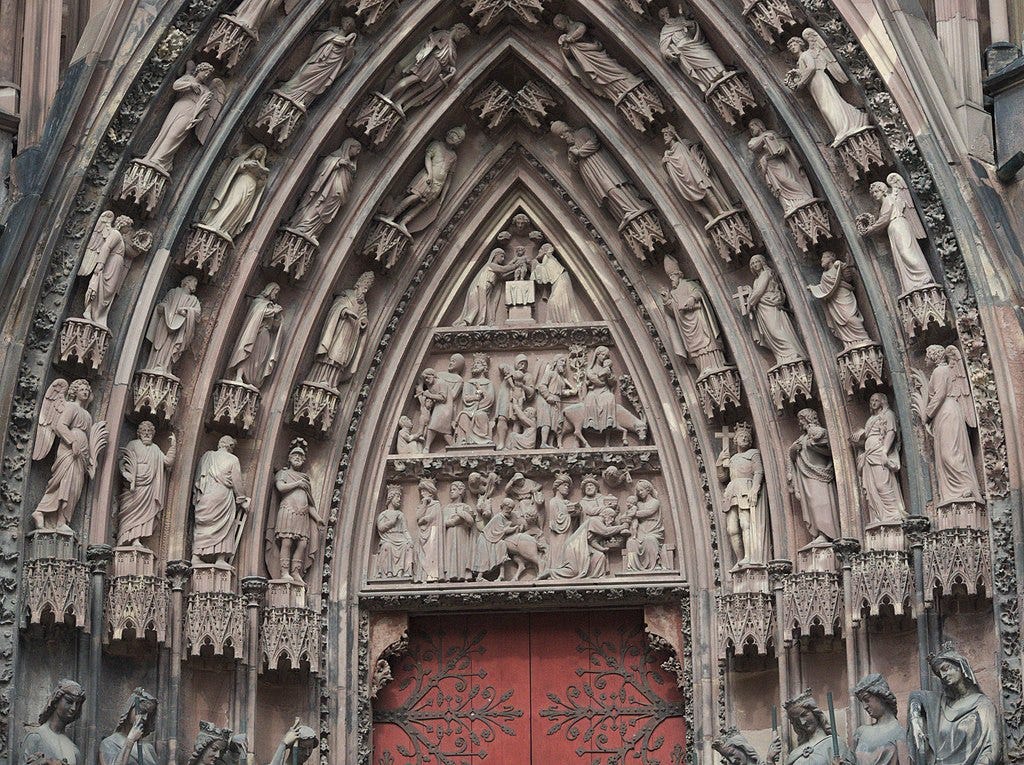

It always begins the same way. Someone standing before a cathedral, staring up at its weathered face and wondering how something still could feel so alive. You can almost hear the echo of chisels; the rhythm of devotion pressed into stone. And then comes the quiet realization that hits like grief: we don’t build like this anymore, not because we’ve forgotten how, but because we’ve forgotten why. John Ruskin saw that loss coming long before the rest of us did.

When he wrote The Seven Lamps of Architecture in 1849, England was booming with iron, coal, and ambition. Factories belched progress into the sky. New cities grew faster than the faith that once grounded them. Ruskin, wandering through Gothic cathedrals of France and England, realized the world had replaced its sacred compass with machinery. The book he wrote was no manual of style—it was a sermon. Each “lamp” wasn’t a rule for builders but a moral law for civilization itself. Architecture, he believed, was not about walls or roofs; it was about the soul made visible.

He began with sacrifice, the first lamp, and the most haunting. For Ruskin, every magnificent building was an offering. The masons of old cathedrals didn’t carve for applause or pay; they carved for God. They worked unseen on spires no one would ever climb, confident that the unseen was still worth doing. True architecture, he said, demanded the surrender of pride. It was art as worship. Yet industrial modernity had made construction a transaction. Sacrifice was gone, replaced by efficiency, and with it, the sacred vanished from the skyline.

Then came truth, a virtue that for Ruskin meant more than honesty; in design, it meant integrity in the very bones of a building. He raged against the fashion of his age: false facades, stone cladding hiding cheap brick, painted vaults pretending to be carved. To him, these were not clever illusions but moral lies. A building, like a person, must be what it seems. When architecture began faking strength, civilization itself began faking meaning. In the end, truth was not a style; it was a conscience.

The third lamp was power. Ruskin didn’t mean dominance or wealth; he meant awe — the kind that makes you stop, look up, and feel small in the best possible way. He studied the bold lines of Greek temples and Gothic spires, seeing in them not arrogance but reverence. Power, he said, is born from proportion, shadow, and scale that remind us of our place in creation. Today, that kind of power is rare. Our cities rise high, but they rarely rise nobly. Their size inspires ambition, not humility.

Beauty followed, his brightest lamp. Ruskin believed beauty was not subjective taste but the reflection of universal order. He told architects to study nature: the curve of a leaf, the branching of a tree, the discipline behind chaos. The Greeks, he said, understood this; their columns echoed living forms, not in imitation but in spirit. Beauty, to him, was moral geometry—truth shaped into grace. Yet as industry gained speed, ornament turned mechanical. Hand-carved patterns gave way to stamped iron and cast molds. The touch of the human vanished, and with it, life.

— Continue reading in the Paid Subscriber’s Edition —

“I believe architecture must be the beginning of arts, and that the others must follow her in their time and order; and I think the prosperity of our schools of painting and sculpture, in which no one will deny the life, though many the health, depends upon that of our architecture.” — John Ruskin.