The Mistake Behind Most New Year’s Resolutions

An Honest Answer

Article by Justi Andreasen, author of Reclaiming the Biblical Worldview

Every January, millions of people make resolutions they will not keep.

The pattern is so predictable it has become a kind of cultural joke. Gym memberships spike in the first week of the year and collapse by February. Diets begin with fanfare and end with quiet resignation. Journals purchased on January 1st sit half-filled by March, then untouched for the rest of the year.

The usual explanations focus on willpower, or the lack of it. We are told that resolutions fail because people set goals that are too ambitious, or because they lack accountability, or because they do not break large aims into manageable steps. The self-help industry has built an empire on this assumption: The problem is technique, and the solution is better technique.

But the sheer scale of the failure suggests something deeper is at work. New Year’s resolutions are not merely difficult. They are structurally misunderstood. We have inherited a ritual whose meaning we have forgotten. And the forgetting is why it no longer works.

In this article, we explore the pre-modern understanding of the turning year, and what it reveals about renewal, time, and the strange logic of genuine transformation…

The Turning of the Year

The ancients did not experience the new year as an arbitrary date on a calendar. They experienced it as a cosmic event.

The winter solstice marked the death of the old sun and the birth of the new. The days, which had been shrinking toward darkness, began once again to lengthen. Light was returning to the world. This was not metaphor. It was the observable structure of reality. A pattern written into the heavens that human beings could witness and participate in.

The rituals surrounding this turning were elaborate and varied across cultures, but they shared a common grammar. The old year had to die before the new could be born. Debts were forgiven. Slaves were temporarily freed. The social order was inverted or suspended. The boundaries that normally structured life were relaxed, allowing something like chaos to flood in, briefly and controlled, before order reasserted itself.

This is the logic of the Sabbath and the Jubilee in the Hebrew tradition: Cyclical returns to more primitive conditions, where what has accumulated is released and what has grown rigid is loosened. The end of the day, the end of the year, these were moments when time itself was allowed to “swallow” the structures that work had built, so that renewal could occur.

The idea is this: Genuine renewal requires a kind of death. You must release the old before the new can take its place. And this release cannot be rushed. It unfolds not according to man, but according to its own rhythm: The sun rising and setting each day, the moon waxing and waning through its course, and the great turning of the year at the solstice.

Leaven and Patience

This logic of renewal-through-release sounds abstract until you see how concretely the ancients understood it. They did not treat time as a neutral backdrop in which things happen, but as an active force that transforms what is placed within it. One of the simplest and most everyday ways they expressed this was through food, especially bread.

“Leaven is essentially a symbol of time. In the biblical worldview, it represents time passing, because that is what fermentation is: letting time work on the dough. Through that waiting, change and transformation take place.”

Matthieu Pageau

Unleavened bread is quick. You mix flour and water, bake it immediately, and the result is flat and dense. Leavened bread requires something else: Waiting. You prepare the dough and then you step back. You let it sit. If you keep kneading, if you refuse to leave it alone, it will not rise.

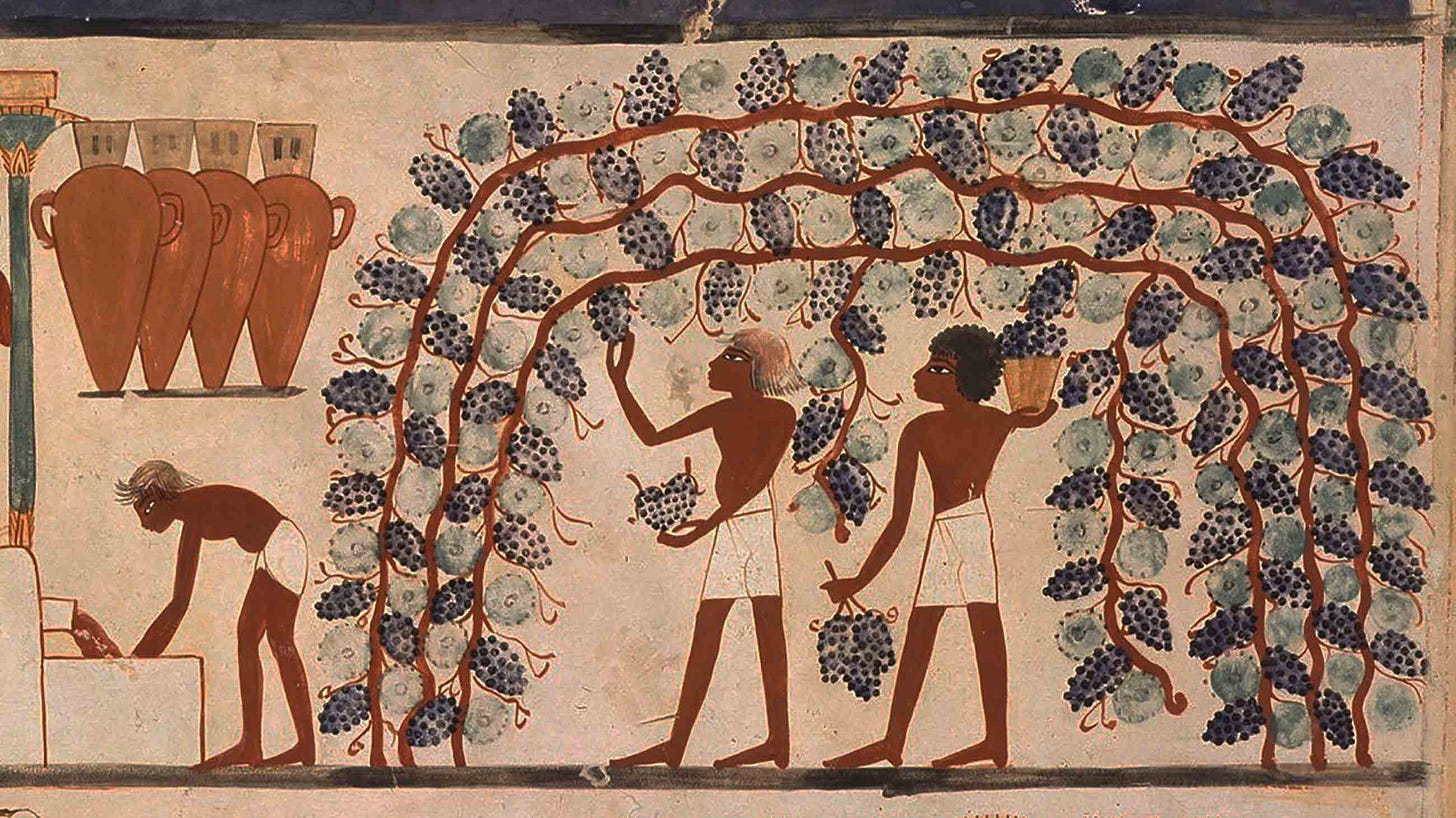

The leaven is time. And time, in the ancient understanding, is closely related to death. Fermentation is controlled decay. You allow something to rot, just slightly, just enough. The paradox is that this small death is what makes the bread soft, what gives it life. Wine works the same way. You let the grapes die, and if you do it skillfully, the result lasts for centuries, and even improves with age.

This is a profound and counterintuitive truth. Renewal is not the same as addition. To stay alive, we must sleep each night, a small death that makes waking possible. In the same way, the sun must set before it can rise again, the moon must wane before it can wax, and the year must pass through its darkest point before the light begins to return. Similarly, you cannot simply pile new habits on top of old ones, or new goals on top of unfinished business. Something must be released. Something must be allowed to die.

Today’s approach to self-improvement resists this logic at every turn. We want transformation without loss, gain without sacrifice, a new self without grieving the old one. We treat January 1st as a starting line, not a threshold. We imagine that we can simply decide to be different, and that the deciding is the hard part, after which everything else is execution.

But the ancients knew that transformation passes through confusion. It requires a descent, a period of uncertainty, a kind of exile, a small death. The Israelites wandered in the desert for 40 years before entering the promised land. Jacob wrestled with an angel through the night before receiving his new name. The seed falls into the ground and dies before it bears fruit.

There is no shortcut through this process. And the attempt to find one, the attempt to seize renewal by force of will, is precisely what causes resolutions to fail.

New Year is one moment within a much larger pattern that governs how light emerges from darkness, how ascent follows descent, and how meaning takes form over time.

The same pattern shapes:

Your seasons

Your struggles

Your calling

Your sense of the sacred

If you want to learn to read that pattern for yourself, subscribe below.

The Impatience of the Golden Calf

If leaven teaches about the consequences of respecting time, the story of the golden calf illustrates the consequences of refusing time.

Moses has ascended Mount Sinai to receive the law. The people wait below. Days pass, then weeks. Moses does not return. The people grow anxious. Is he alive? Is he dead? How long are they supposed to wait?

Eventually, they decide they cannot wait any longer. They ask Aaron to make them a god. Something visible, something present, something that will lead them forward. Aaron melts down their gold and fashions a calf. The people celebrate. They have taken matters into their own hands.

When Moses finally descends, he is furious. The people broke the covenant before it was even delivered. Their impatience has led them into idolatry.

The calf is a terrestrial creature associated with the wagon and circular motion (like a wheel or the sun disk). It symbolizes a kind of existence that is earthbound. This makes the golden calf an image of movement without ascent, change that goes nowhere. What the people wanted was not unreasonable. They wanted to move forward. They wanted to be renewed. Moses had seemingly abandoned them, and they did what people always do when left in uncertainty. They tried to force the transformation themselves.

This is the temptation of every New Year’s resolution.

We sense that something needs to change. We feel the weight of the old year: Its failures, its disappointments, its accumulated drift. We want to be different. And so we make declarations. We set goals. We construct elaborate systems of accountability and measurement. We try to manufacture renewal through planning and effort.

But one cannot seize genuine renewal. It must be received. The difference between the golden calf and the tablets of the law is the difference between self-generated transformation and transformation that comes from beyond oneself. One is idolatry. The other is covenant.

Two Kinds of Descent

The ancient world understood that there are two kinds of descent. One leads to ascent and new life, the other keeps you down. One is like sleep that restores you. The other is sleep from which there is no waking.

The distinction is subtle. Both involve change. Both involve letting go of the old. But one is patient and the other is grasping. One submits to the rhythm of time, and the other tries to force time’s hand. One waits for the bread to rise, and the other keeps kneading. One waits to receive, and the other seizes the fruit for itself.

This is the knowledge that most New Year’s resolutions lack.

We approach January with the spirit of the golden calf:

· Impatient

· Anxious

· Determined to make something happen.

We treat the new year as a problem to be solved, a project to be managed. We forget that the turning of the year is not primarily an opportunity for self-improvement. It is a threshold, a liminal space, a moment that temporarily suspends the normal structures of life, allowing something deeper to set it right.

Receiving What Must Be Done

Renewal is not first a matter of choice, but of attention.

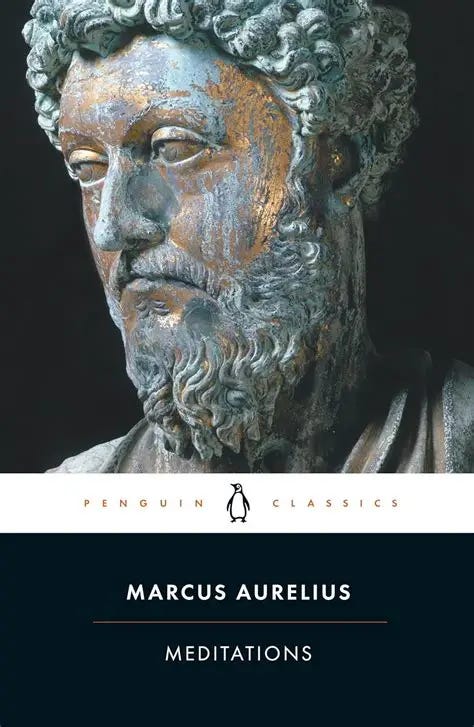

The turning of the year is not a moment to impose new plans, but a pause where ordinary structures loosen, allowing a higher order to become visible. Prayer and fasting, which traditionally accompany the Advent season, are not acts of self-denial for their own sake, but ways of quieting the noise that prevents deeper perception.

This is why leaven requires waiting. You do not force the dough to rise. You prepare it, step back, and allow time to reveal what is already at work.

Modern resolutions fail because they reverse this order. We act before we see and decide before we listen.

Christmas takes place at the solstice for the same reason. The Incarnation is not a human project. It is revelation received. Light enters the world while humanity waits in darkness.

The resolutions that hold are not made up but disclosed. They emerge from contemplation, reflection, and honest attention to what the past year has disclosed. They are responses to a higher clarity, not assertions of control.

The new year is not asking what you plan to do.

It is asking whether you are still enough to see what must be done.

Most New Year’s resolutions fail because they focus on habits, not the person underneath them.

This December, I spent twelve days studying twelve Christian thinkers who asked a deeper question: Who do you need to become before anything else can change?

What came out of it was formation.

The 12 Gifts of Christian Theology isn’t about doing more in the new year.

It’s about seeing more clearly, wanting better things, building an inner life that doesn’t collapse under pressure, and understanding why longing never fully goes away.

If you’re tired of setting goals that don’t last, this series gives you something sturdier to stand on: identity, clarity, courage, wonder, discipline, joy, and meaning.

All twelve essays are available to paid subscribers, with a collected e-book coming in January.

If you want to enter the new year changed, not just organized, this is where to begin.

Click below…

I learned a lot from this article

Paradox before progress. Darkness before light. Death before life.

Much food for thought here, Justi. Thank you