The Painting That Killed the Romance of War

Goya's Third of May 1808 painted the moment before death, so we’d never look at war the same way again.

Most war paintings lie. They wrap violence in glory and sacrifice, convincing us that death for a cause is beautiful. Francisco Goya tore that lie apart. The Third of May 1808 doesn’t honor war. It condemns it. A man in white kneels in front of a firing squad, arms raised, eyes wide, mouth open in a scream that still echoes two centuries later. He’s not a soldier. He’s a civilian. And he’s about to die.

Goya painted what he saw when Napoleon’s army invaded Spain. The French promised liberty. What they brought were mass executions. On May 3rd, 1808, they marched Spanish citizens into open squares and shot them without trial. Goya turned that trauma into one of the most haunting paintings in history.

Look closer. The lantern in the center doesn’t light hope, it exposes horror. The soldiers’ faces are hidden. They look like a machine. Rifles point in unison, cold and merciless. Meanwhile, the victims show everything: fear, despair, disbelief. It’s a reversal of the usual war scene. The killers have no soul. The dying have all the humanity.

That man in white looks like Christ, but Goya wasn’t painting a resurrection. He was painting annihilation. Blood pools at his feet. Bodies lie in heaps beside him. There's no salvation here, only silence and the cold efficiency of empire.

This wasn’t just a Spanish tragedy. Goya was making a universal statement: this is what power does when no one stops it. He didn’t romanticize. He didn’t filter. He wanted you to feel what he felt helpless, furious, sickened.

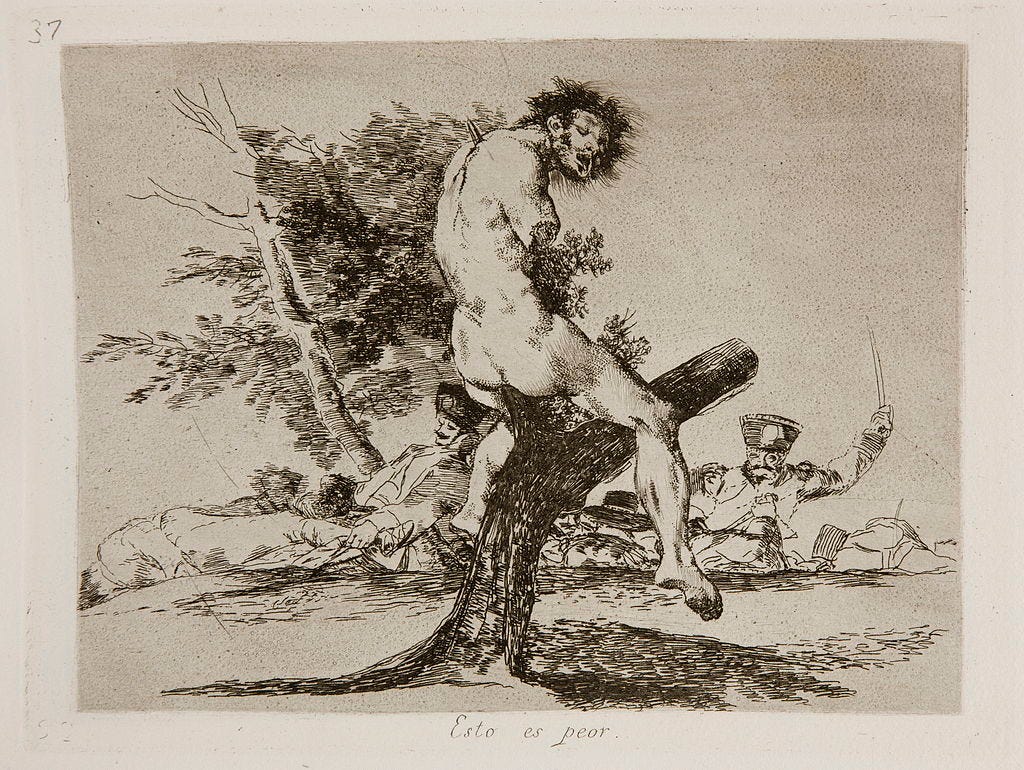

And he didn’t stop. Goya created The Disasters of War, a series of etchings that plunge deeper into human cruelty. One of the most infamous is titled This is worse. It shows a mutilated corpse hanging from a tree, limbs hacked off, horror frozen in his eyes. There’s no caption explaining the context. Goya lets the image speak—and it screams.

As Spain collapsed and politics failed him, Goya’s health did too. He lost his hearing. The world around him became even more distant. He withdrew, isolated himself, and began to paint not for anyone else, but for his own sanity. From that darkness came the Black Paintings.

He painted them directly onto the walls of his house. No commissions. No audience. Just raw expression. These works were private nightmares, never meant to be seen. Among them is the infamous Saturn Devouring His Son, where the Roman god tears into his child with wild, bulging eyes and bloodied hands.

Goya didn’t paint mythology. He painted fear. He saw Saturn not as a god but as a mirror. What happens when power eats its future to preserve itself? What happens when we lose reason, compassion, and control?

He lived alone, surrounded by these monstrous visions. Every day, he woke up to images of madness and violence. It wasn’t decorative. It wasn’t symbolic. It was personal. He painted what it felt like to lose faith in humanity.

And yet, despite the horror, his work remains astonishingly honest. Goya never looked away. He forced us to confront what we try to hide: that humans can be both the victims and the monsters. That civilization rests on a fragile edge.

Today, The Third of May 1808 hangs in the Prado Museum in Madrid. Visitors still stand frozen before it. Some cry. Some look away. Few forget it. Because it still speaks—not just about the past, but about what we’re capable of, even now.

Goya didn’t set out to be a prophet of horror. But in revealing the worst of us, he preserved a sliver of truth. And maybe that’s what art is for—not to decorate, but to make sure we never forget.

https://cultureexplorer.gumroad.com/l/zzuhuz

Astounding artist

To be upfront, I didn't read the article, I'm reacting to the title. If the title is true, then what about the photos taken at the beginning of World War I with girls kissing soliders and soliders with flowers in their rifle barrels? 🤔