The Rise and Betrayal of the Knights Templar

Fear, not faith, sealed their fate.

The story of the Knights Templar begins with shock. In a world where monks prayed and knights killed, no one expected the two roles to merge. Yet, in 1119, nine knights in Jerusalem swore vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience while also promising to fight. That act set the stage for one of the most powerful and controversial orders in medieval history.

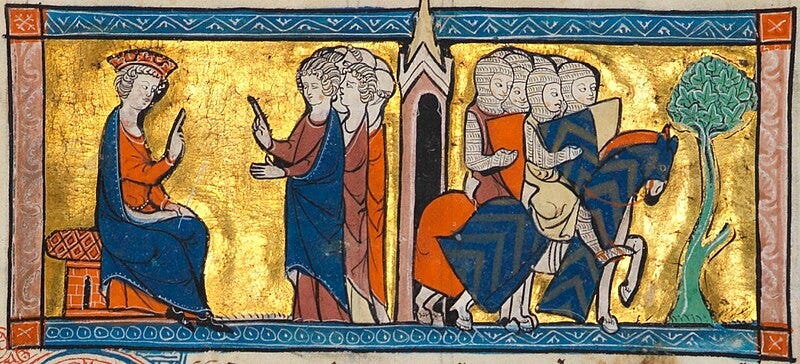

At first, their mission seemed narrow: protect Christian pilgrims on the dangerous roads of the Holy Land. But their chosen headquarters gave that mission extraordinary weight. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem housed them on the Temple Mount, in a wing of the former Al-Aqsa Mosque, itself built on the ruins of what many believed was Solomon’s Temple. To medieval eyes, this was no coincidence. The knights were living atop the most sacred ground in Christendom, tied directly to the memory of David, Solomon, and the Temple of God.

From that perch, the Templars became more than guards of roads. Chroniclers whispered that they dug beneath the Temple Mount in search of relics or ancient wisdom. Whether true or not, the association between the order and hidden treasures of biblical times never faded. The very name “Templar” bound them forever to Solomon’s Temple, giving their work a divine aura that no other order could claim.

Theologians gave them legitimacy. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the great voices of the twelfth century, called them “new knights.” Unlike worldly warriors, he said, these men fought not for gold or glory but for God. His words gave the Templars moral authority and a flood of recruits.

The Church went further. Pope Innocent II granted them extraordinary privileges. They answered only to him. They could collect donations, take spoils of war, and operate across Christendom without interference from local bishops. In a medieval world where every institution was hemmed in by feudal ties, the Templars stood apart, free and unshackled.

That freedom, combined with their base on the Temple Mount, gave the order unmatched spiritual credibility. They were not just knights, they were custodians of the very ground where Christ had walked, where prophets had prayed, where God’s temple had once stood. It was as if heaven itself had endorsed their cause.

With papal backing and holy prestige, the Templars expanded rapidly. Castles, estates, and treasure poured in from nobles eager to secure spiritual rewards. Donations of land in France, Spain, and England funded their work in the East. Even small gifts from peasants added to their growing network of wealth and power.

They soon became more than a band of warrior-monks. They built fortresses across the Holy Land, standing as bulwarks against Muslim armies. Their red cross on a white mantle became a feared sight in battle. Chronicles describe them charging in disciplined lines, willing to die rather than retreat.

But their power also rested on something new: finance. They pioneered forms of banking that allowed pilgrims to deposit money in Europe and withdraw it in Jerusalem. Kings entrusted their treasuries to them. Estates were managed like businesses. The Templars became not just warriors but also financiers, their influence stretching from farm fields to royal courts.

This wealth bred suspicion. Some saw them as holy protectors. Others saw arrogance. William of Tyre accused them of pride, noting their role in the loss of Ascalon. Enemies whispered that their secretive rituals hid corruption. The aura of mystery surrounding their life on the Temple Mount only deepened these suspicions.

For nearly two centuries, though, their position held. They fought in every major Crusade, stood at the forefront of battles, and bled heavily in defeats. When Jerusalem fell in 1187, Templars were among those executed by Saladin. Their loyalty to the cause was unquestioned, even if their victories diminished with time.

The fall of Acre in 1291 marked a turning point. With the last Crusader stronghold in the Holy Land gone, the Templars lost their central mission. They retreated to Cyprus, still wealthy, still organized, but now a powerful order without a battlefield to justify their existence.

That vacuum made them vulnerable. King Philip IV of France, buried in debt to the Templars, saw an opportunity. On October 13, 1307, a Friday, his agents arrested Templars across France. The charges were shocking. Heresy, blasphemy, obscene rituals. Many confessed under torture.

The spectacle stunned Europe. An order once hailed as defenders of Christendom was now branded as traitors to Christ. Trials dragged on for years. Popes hesitated, but political pressure mounted. The balance of power had shifted: kings were stronger, the papacy weaker, and the Templars caught in the middle.

Philip’s motives were transparent. By destroying the Templars, he erased his debts and seized their wealth. But he cloaked his ambition in moral outrage, framing himself as a defender of the faith. It was a masterstroke of politics disguised as piety.

The trial exposed contradictions in medieval law. Confessions extracted under torture were accepted as evidence. Rumors were treated as fact. The Templars’ own strict rules of secrecy made them easy targets. Practices meant for discipline looked sinister when twisted by enemies.

In 1312, Pope Clement V, under immense royal pressure, formally dissolved the order. The Templars’ properties were transferred to the Hospitallers, though kings often kept the choicest lands. What remained of the order’s independence vanished overnight.

The final act came in 1314. Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master, was burned at the stake in Paris. Chroniclers say he declared the order’s innocence and summoned his persecutors to divine judgment. Within a year, both Pope Clement and King Philip were dead. Legends grew from that eerie timing.

From that moment, the Templars passed into myth. Friday the 13th, once an ordinary day, gained its dark reputation. Rumors of hidden treasure, secret rites, and survival in exile spread across Europe. For centuries, writers, freemasons, and novelists would keep the legend alive.

Yet the reality is both simpler and more tragic. The Templars rose because the medieval world needed them—monks who could also fight, bankers who could also pray. They fell because politics turned against them. Their wealth and independence made them too dangerous to tolerate.

Their story reveals the fragility of power in the Middle Ages. A papal bull could elevate a handful of knights into an international force. A king’s warrant could erase them just as quickly. Faith and politics, so closely tied, made saints into heretics overnight.

But the fascination endures because the Templars stood at the crossroads of ideals and corruption, of faith and force. They show how an institution can embody both devotion and ambition, both sacrifice and pride.

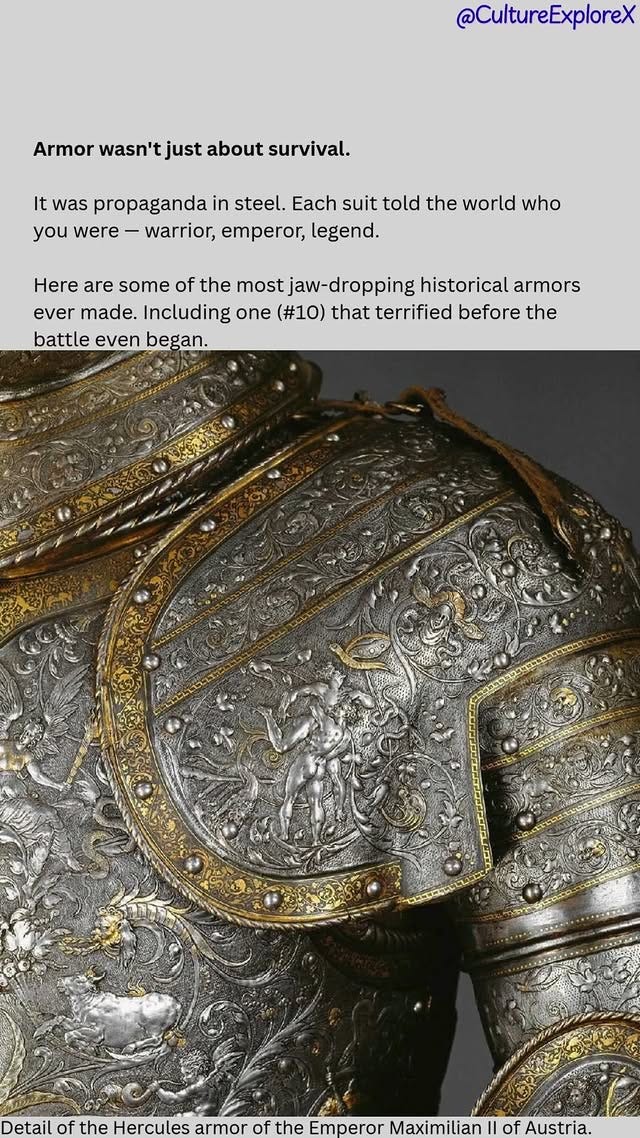

Even their symbols tell the story. The red cross on white cloth was meant to show purity and sacrifice. After their fall, it became a mark of secrecy and conspiracy. Meanings shifted as memory blurred history.

Modern historians strip away the myths to reveal the political machinery behind their fall. Yet the persistence of legend shows how deeply people crave mystery. The Templars left enough gaps in the record to fuel centuries of speculation.

Their rise also sheds light on medieval society itself. The blending of monk and knight reveals a culture grappling with violence, trying to sanctify it, and never fully resolving the contradiction. The Templars embodied that tension more visibly than anyone.

Their fall, in turn, reveals how power devours even its most loyal servants. The same Church that had exalted them abandoned them when kings demanded it. The same crowds that cheered them on the battlefield watched them burn in Paris.

Yet the Templars endure in memory because they died dramatically. Had they simply faded after Acre, they might have been forgotten. Instead, their trial turned them into martyrs of a sort — innocent or guilty, they were destroyed not in battle but in court.

That contrast is why they still haunt imagination today. Warriors should die with swords in hand, not under chains in a dungeon. Their unnatural end begged for explanation. Conspiracy theories filled the void.

But the real lesson of the Templars is not treasure or secret knowledge. It is the danger of standing between faith and politics, between wealth and kings. They show how quickly admiration can turn to fear, and fear into destruction.

Even now, when people speak of Friday the 13th or hidden treasure under Rosslyn Chapel, they are really speaking of a deeper unease. The Templars remind us that institutions, no matter how powerful, can fall in an instant when power shifts.

Their story is not just medieval. It is timeless. Power creates suspicion, wealth breeds enemies, and secrecy feeds imagination. That is why the Templars remain alive in our culture long after their ashes cooled in Paris.

And maybe that is the most fitting legacy. They lived by vows of poverty yet became rich, vowed obedience yet grew independent, vowed chastity yet were accused of perversion. They embodied contradictions that could not survive, but that still fascinate.

The Templars remind us that history is not only about facts but about meanings. Their rise tells us what medieval society valued: faith, protection, unity. Their fall tells us what it feared: independence, wealth, secrecy. Between those poles lies their enduring mystery.

But their downfall is only half the story.

For centuries after their ashes cooled in Paris, whispers spread of a treasure never found, one that might explain why kings moved so ruthlessly against them. Some said it was silver and gold. Others swore it was something far more powerful.

What if the real reason the Templars still haunt our imagination is not their fall… but what they may have carried away before it?

👉 Unlock the Premium Edition to discover how the Knights Templar became forever bound to the greatest legend in Christendom: the Holy Grail.

Upgrade to Premium to Continue Reading…