The Shah and the Cleric: Iran’s Fatal Choice Between Progress and Soul

Why Governing Without Legitimacy Always Ends in Revolt

Iran’s revolution is often reduced to a morality play. A corrupt king falls. A pious cleric rises. But this framing collapses the moment you look closely at how ordinary Iranians actually lived under each system. The truth is harder and more unsettling.

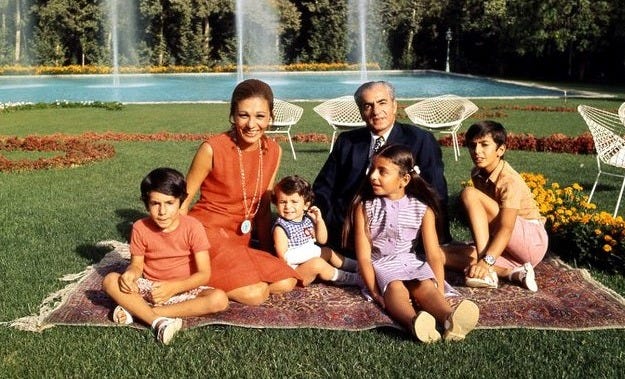

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi did not rule a medieval backwater. By the mid-1970s, Iran was one of the fastest-growing economies in the developing world. Oil revenues jumped from roughly $2.5 billion in 1972 to over $20 billion by 1976. Tehran exploded with construction. Universities multiplied. Literacy campaigns reached rural villages for the first time.

Women entered universities in unprecedented numbers. By 1977, women made up roughly one-third of university students. The Family Protection Law expanded women’s rights in divorce and child custody. These were not symbolic gestures. They altered real lives.

Yet political life moved in the opposite direction. In 1975, the Shah abolished all political parties and replaced them with a single mandatory party, the Rastakhiz Party. Membership was not optional. Refusal could cost you your job or land. Modernization came with compulsory loyalty.

The security apparatus enforced this order. SAVAK maintained tens of thousands of informants. Former detainees consistently described electric shocks, mock executions, and prolonged solitary confinement. These were not rumors. They appear repeatedly in court testimonies and academic investigations.

The Shah justified this repression as necessary for stability. He argued that Iran lacked the political culture for democracy and needed “guided development.” But the result was a society where engineers, doctors, and students lived materially better while feeling politically suffocated.

One striking example came in 1977 when a group of Iranian intellectuals wrote an open letter demanding constitutional rule and an end to arbitrary arrests. The letter did not call for revolution. It asked for laws already on the books. Many signatories were harassed, detained, or forced into silence.

This gap between legal modernity and political reality widened resentment. The Shah’s state looked powerful, but it felt brittle. When protests began in 1978, they spread faster than the regime expected precisely because no legitimate outlet for dissent existed.

Religion filled that vacuum.

Ruhollah Khomeini did not emerge from nowhere. He had opposed the Shah’s White Revolution as early as 1963, especially land reform imposed without clerical input and expanded rights for women that bypassed religious authority. His arrest that year triggered mass protests and dozens of deaths.

Exiled first to Turkey, then Iraq, and finally France, Khomeini refined a simple message. The Shah was not just a dictator. He was illegitimate. He ruled through foreign backing, moral corruption, and violence against his own people.

Cassette tapes of Khomeini’s sermons were smuggled into Iran and played in bazaars and mosques. This was grassroots media before social media. His words reached factory workers, shopkeepers, and rural migrants who felt alienated by elite modernization.

The revolution succeeded not because Iranians rejected progress, but because they rejected being ruled without voice. When soldiers refused to fire on protesters in early 1979, the monarchy collapsed within weeks. What followed, however, was not pluralism.

Within months, revolutionary courts began executing former officials after trials that sometimes lasted only minutes. By the end of 1979, hundreds had been executed. Due process, which had been denied under the Shah, did not suddenly appear. It was redefined as unnecessary.

The new Islamic Republic rewrote legitimacy itself. Sovereignty no longer rested with the people, but with divine guardianship. The doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih placed ultimate authority in the hands of a supreme jurist.

Elections continued, but only candidates approved by clerical bodies could run. Newspapers were shut down for “corrupting public morality.” Leftist allies of the revolution were purged, imprisoned, or executed by the early 1980s.

Women experienced the shift immediately. Mandatory hijab laws were enforced by state power. The Family Protection Law was repealed. Testimony by women in court was devalued. The same revolution that mobilized women in the streets narrowed their legal space afterward.