The Tale of Genji Is the First Psychological Novel

Japan’s first novel exposed modern emotional traps.

You can watch a man climb the heights of power, seduce the most beautiful women, and master the rituals of a golden court and still feel that he is emotionally hollow.

That’s the brilliance and ache of The Tale of Genji.

Written over a thousand years ago by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the Japanese imperial court, this novel isn’t just one of the world’s first long-form fiction, it’s the first great psychological novel, too. And that changes how we read it.

At first glance, it seems like a series of romantic escapades wrapped in silk. But stay with it long enough, and you begin to notice something deeper. Genji, the dazzling protagonist, is charming and cultured. But he’s also trapped in his desires. He cannot stop himself from chasing what he cannot have, nor can he ever hold on to what he wins. He’s the kind of man who confuses longing with love and you feel it in every chapter.

The emotional complexity we admire in modern fiction was already being explored in the 11th century by Murasaki Shikibu. She didn’t just anticipate it she laid the foundation for it. And she did it not from the center of power, but from the margins, a woman writing in a world that mostly silenced women.

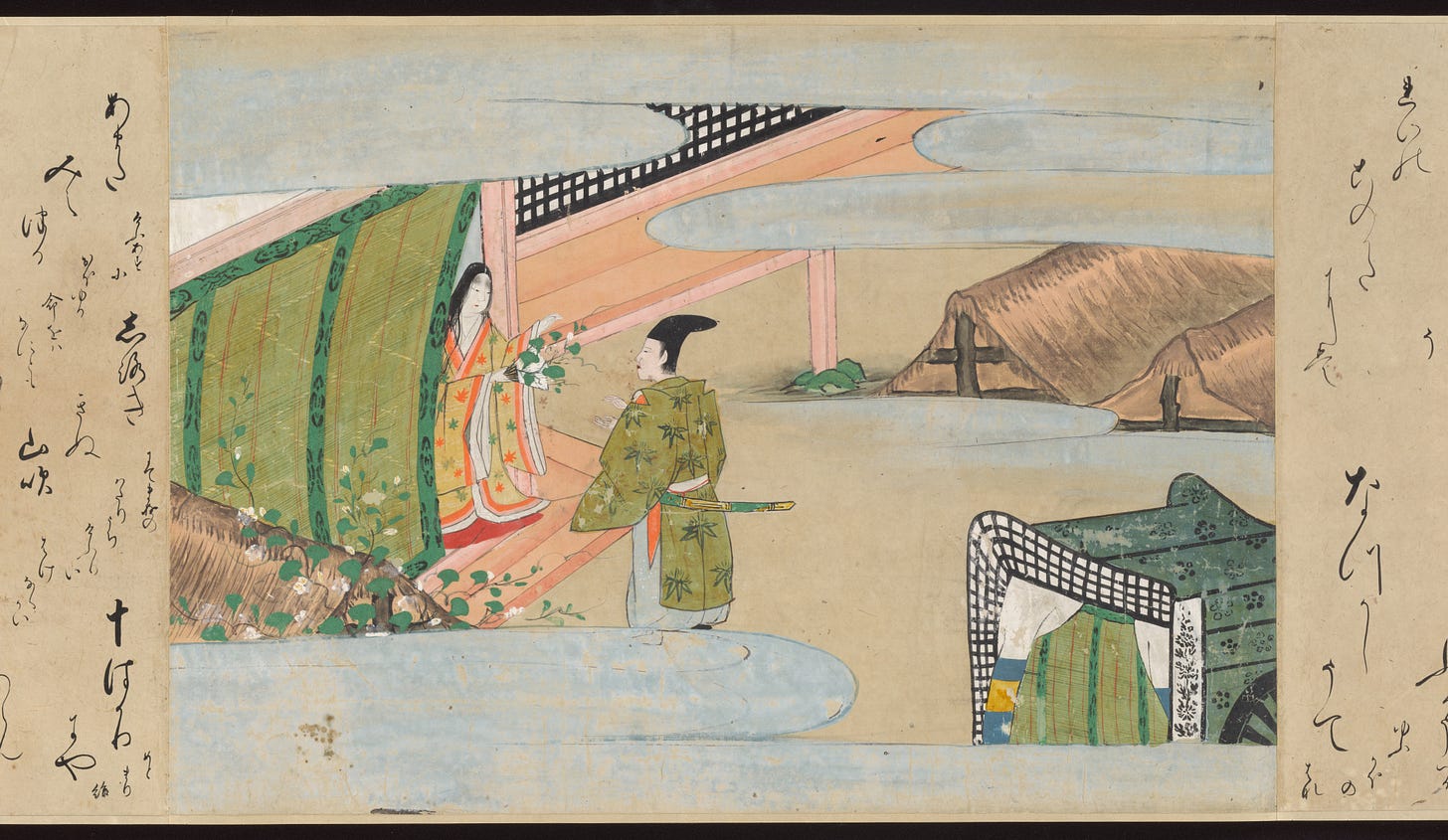

You could argue that The Tale of Genji is less about Genji himself and more about the emotional wreckage he leaves behind. Women fall for him, lose themselves, fade away. But they’re not just victims. Murasaki gives them voice, inner life, and emotional clarity Genji himself often lacks.

Take Lady Rokujo, for example. She is older, proud, and fiercely intelligent. Her jealousy isn’t cartoonish. It consumes her, then detaches from her like a spirit. Her torment becomes supernatural. The story never confirms she’s possessed, but that uncertainty makes it all the more disturbing. She’s a woman who cannot openly express grief, rage, or loss so her emotions erupt in another form.

That’s psychological storytelling.

Genji doesn’t understand her, of course. He rarely understands any of them. He idealizes Murasaki, the girl he raises to become his perfect woman. But what he loves is his illusion of control, not her individuality. Even as she withers away in her later years, Genji’s gaze remains fixed on his past vision of her.

It’s brutal. And yet, it’s not cynical. Murasaki Shikibu doesn’t mock Genji. She examines his thoughts, motivations, and contradictions. Instead of judging him, she reveals the emotional instability hiding beneath his polished appearance.

There are moments when he genuinely mourns. When his political fortunes rise, he still grieves what he’s lost. When he hears a familiar melody, it brings back an old lover’s voice. The past clings to him. And that’s when you see his real tragedy: not that he loved too many, but that he never truly knew how to love.

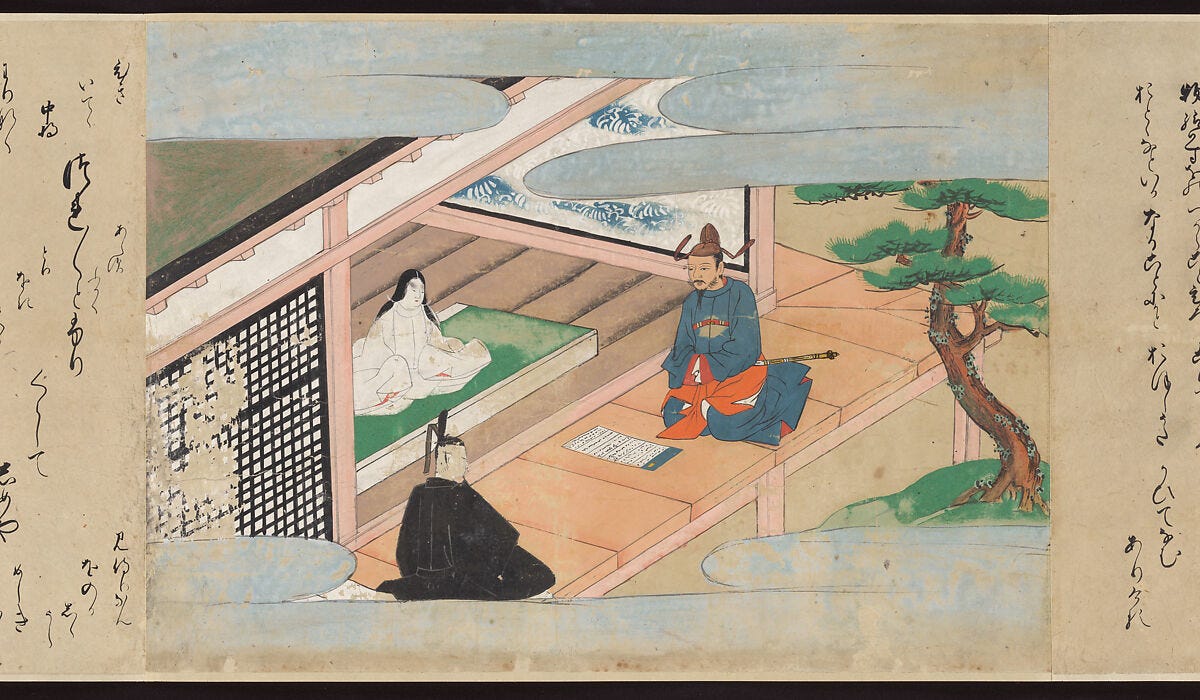

Modern readers sometimes miss that subtlety because they expect plot. The Tale of Genji doesn’t provide that. It lingers. The seasons change. A fan closes. A note is burned. A plum blossom falls. These moments aren’t just aesthetic; they're emotional also.

Murasaki understood how human emotions are shaped by time, by place, by silence. Her characters don’t shout their feelings. They hint, reflect, regret. Sometimes their love is expressed in poetry, sometimes in illness. There are whole chapters where nothing "happens," but everything shifts. That’s psychological realism before the term even existed.

Even when Genji reaches the height of power as an honorary emperor, there's no emotional payoff. The storytelling becomes subdued. Instead of glory, there’s detachment. Murasaki doesn’t praise his triumph, she lets it pass without fanfare, as if power itself has lost meaning., she lets it sit like cold incense.

And then he disappears. The novel doesn’t end with Genji’s death. Instead, we enter the world of his descendants, who seem even more emotionally fragile. The final chapters often called the Uji chapters are darker, lonelier. Characters like Kaoru and Niou move through the same cycles of desire and regret, but with even less certainty.

This shift matters. It’s as if Murasaki is saying: Genji wasn’t a hero. He was a symptom. The disease is deeper, a society obsessed with beauty, status, and illusion. What we inherit is not just Genji’s legacy, but his emptiness.

And yet, the novel never lectures. It shows. It lets you feel. That’s why it works.

There’s also the question of authorship. Murasaki was writing in kana, the women’s script. The men wrote in Chinese. She was creating a new form of literature in the voice of the marginalized. Her choice of language shaped how emotions were expressed — subtle, poetic, reflective.

She also wrote from experience. Murasaki knew court life. She had seen its vanities. Her own diary reveals a woman of sharp insight and quiet melancholy. She saw how women were praised for their beauty, used for alliances, and then left behind. She poured that understanding into every female character.

There’s no true villain in Genji. There’s no pure victim either. Everyone is compromised by desire, memory, or illusion. That’s what makes it so human.

Even the aesthetics serve a psychological purpose. When a character admires moonlight or weeps over spring blossoms, it’s not just decorative. It’s emotional displacement. They can’t say what they feel, so they let nature say it for them.

In that way, Genji anticipates Freud. It anticipates Proust. It anticipates every novel where the real action is in the mind.

And perhaps that’s why it still resonates. Not because of Genji’s beauty or the elegance of Heian life, but because it understands something universal:

We all chase shadows. We all misread love. We all live in the gap between who we are and who we pretend to be.

Murasaki saw it first. And she didn’t flinch.

Murasaki didn’t just portray emotional damage, she revealed how it emerges, and what allows it to heal. These six strategies are grounded in moments from the novel that still feel familiar today. Each offers a practical shift in thinking for anyone stuck in cycles of self-deception, shallow connection, or emotional burnout.

Stop idealizing people. Genji idealizes women like Lady Fujitsubo and Murasaki, only to be devastated when they reveal emotional limits or agency. Readers can reflect: are you chasing a person, or an image you invented? The moment Genji sees Fujitsubo as a symbol rather than a woman, he begins to lose her.

The next five strategies are beyond the paywall.