The Vatican in 30 Artworks

What to see first and why it matters?

Beauty is not a luxury in the Vatican. It’s the point, and it hits you like a verdict the moment you step in.

Here’s the conversation we should be having as we walk: what deserves your attention first, what cannot be missed, and how the greatest works talk to each other. I’m ranking the 30 best from first to last so you can move with purpose, not drift. If we do this right, you’ll walk away with a framework that makes sense, not just a visual overload.

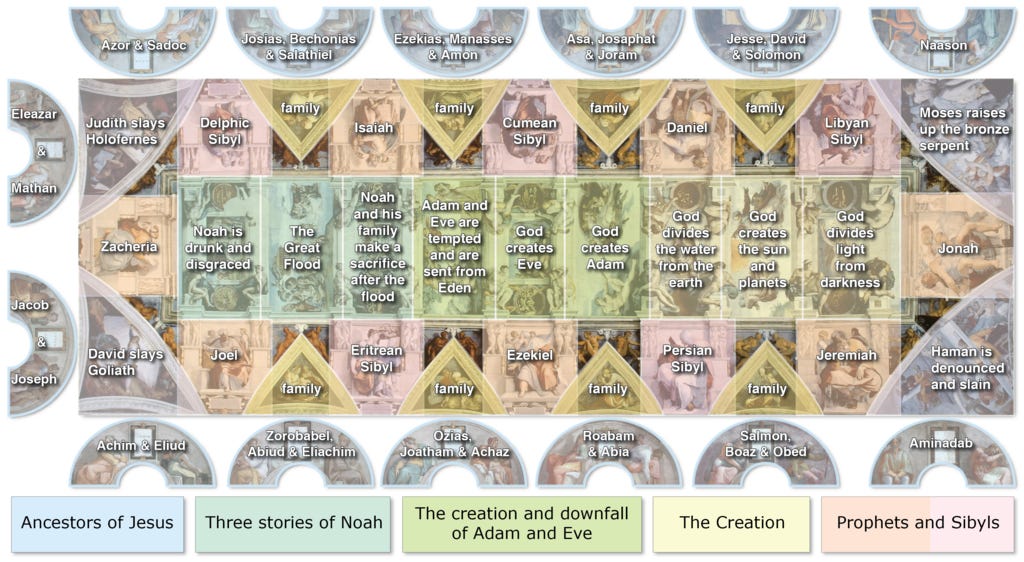

At number one, Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling is the summit. Nine central scenes from Genesis, with the Creation of Adam as the keystone, make the Bible feel like muscle and breath. Stand on the far end from the entrance to feel the sequence open up and watch Michelangelo grow bolder panel by panel.

Second is the Last Judgement, the back wall of the Sistine Chapel. It is not polite. It is a reckoning in fresco, a vortex of bodies, trumpets, books, angels, and demons with Christ at the center as judge. Find St. Bartholomew holding his flayed skin. Michelangelo’s face is in it. That’s the level of risk he took.

Third is Raphael’s School of Athens in the Room of the Segnatura. Harmony, intelligence, and human scale hold. Plato and Aristotle anchor the center; Leonardo’s face is Plato, Bramante is Euclid, and Raphael sneaks himself in at the edge. It’s the Renaissance explaining itself.

Fourth is Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s. Marble turned soft. A young Mary cradles a dead Christ with a grief so controlled it hurts. Michelangelo signed the sash after hearing people credit a “Milanese” sculptor. He never signed again.

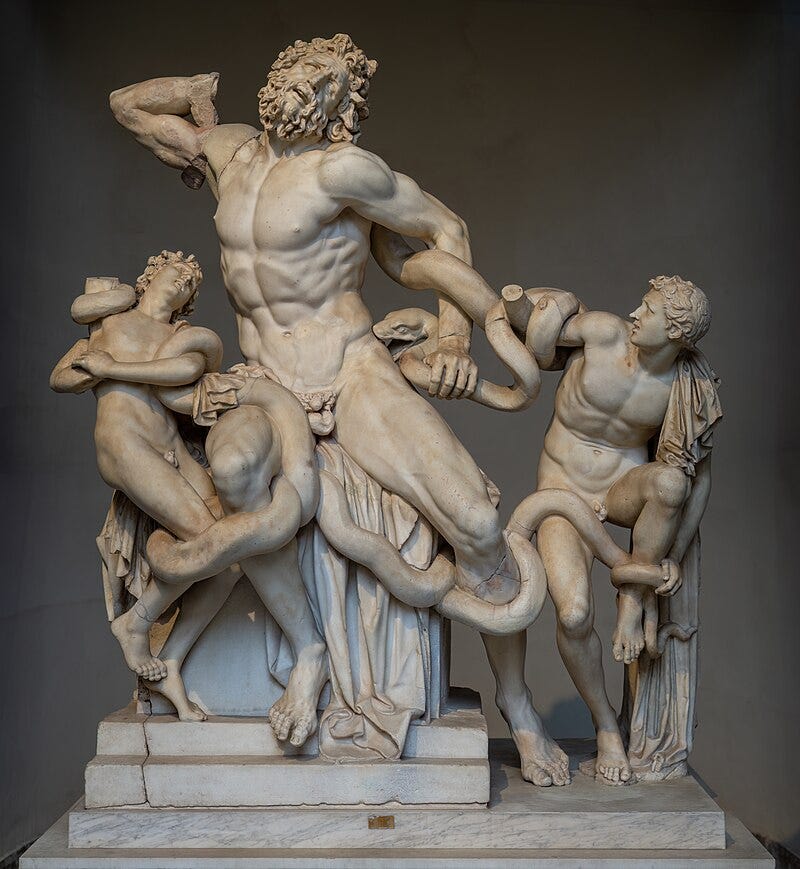

Fifth is the Laocoön Group. The priest who warned Troy about the horse dies with his sons in a tangle of stone and serpents. When they found it in 1506, the right arm was missing. Michelangelo said it should be bent. The later discovery proved him right.

Sixth is the Belvedere Torso. A fragment that changed how bodies are imagined. Every twist of its trunk is studied and alive. Michelangelo used it as a grammar book for anatomy. You’ll see its turn echoed across the Sistine angels.

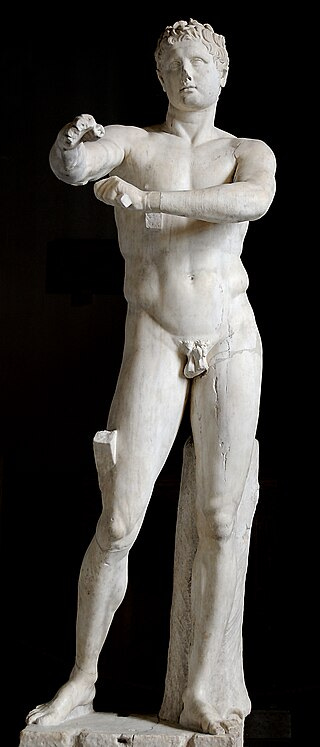

Seventh is the Apollo Belvedere. Roman copy of a Greek bronze, poised after the shot. Winckelmann called it the ideal of ancient art. Look at the hair, the cloak, the controlled movement. Then compare the head to Christ in the Last Judgement—it’s a quiet influence.

Eighth is Raphael’s Transfiguration in the Pinacoteca. Two stories stacked in one: a sick boy below, Christ in glory above. Raphael pulls your eye up with color alone, darker at the bottom, blazing at the top. It was laid over his coffin. It feels like a farewell.

Ninth is Perugino’s Handing Over the Keys in the Sistine side walls. A crisp lesson in perspective and authority. Peter kneels, Christ gives the two keys, and an “ideal city” stretches back to paired arches of Constantine. Its theology rendered as urban design.

Tenth is Raphael’s Liberation of St. Peter in the Room of Heliodorus. Three light sources—moonlight, torchlight, and the angel’s blast break the scene apart. The chain falls. The guards freeze. Light itself does the saving.

Eleventh is Caravaggio’s Deposition (The Entombment of Christ). Christ is lowered onto the anointing stone, darkness crushes the background, and grief has weight. Nicodemus grips the body with his thighs and forearms. There is nothing “ideal” here, only truth.

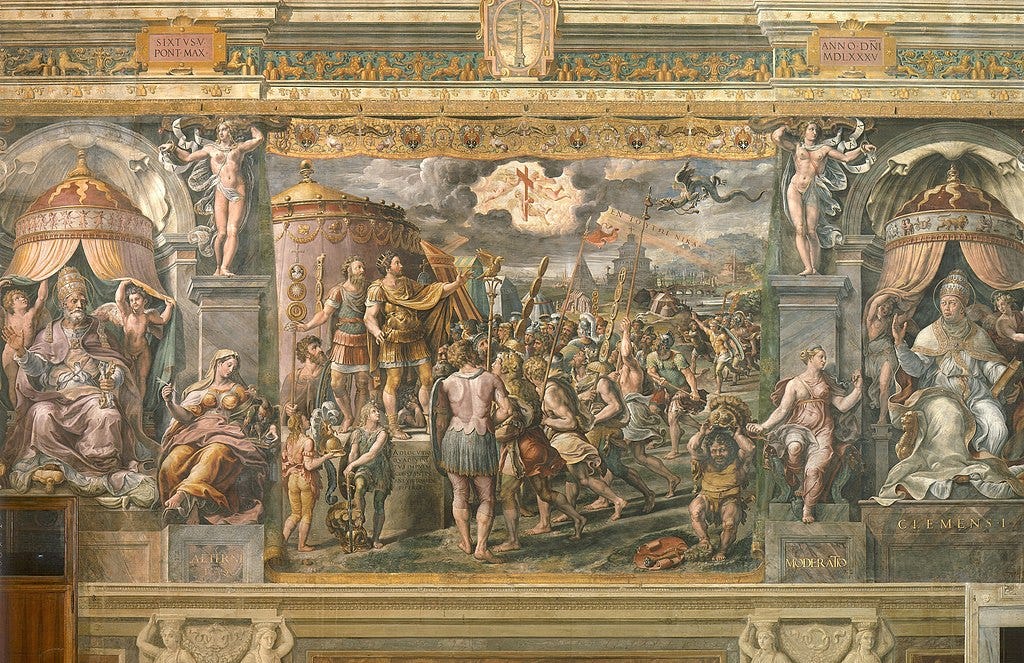

Twelfth is the Battle of Milvian Bridge in Raphael’s rooms. It’s spectacle with a point: victory under the sign of the cross. White horse for Constantine, a panic of bodies and splashes for the defeated. History made legible in one glance.

Thirteenth is Leonardo’s St. Jerome (unfinished). The gaunt face, the lion at his feet, the stone in his hand. Penance and mind. The panel’s journey is a story on its own, found in pieces as a box lid and a cobbler’s stool cover, then made whole again.

Fourteenth is Bernini’s Baldacchino over St. Peter’s high altar. Bronze spiral columns pull your eyes up into the dome. Ninety-five feet of choreography tie Maderno’s nave to Michelangelo’s vault. It solves a problem and becomes a landmark.

Fifteenth is the Gallery of Maps. A cartographic corridor painted for a pope who fixed the calendar. Italy unrolls in green and gold on both sides. Look up: the ceiling is a running cast of saints and martyrs that aligns with the geography below.

Sixteenth is Raphael’s Vision of the Cross in the Room of Constantine. The omen appears; the decision becomes history. A dwarf court jester holds a helmet in the foreground—a sly wink amid a turning point.

Seventeenth is Raphael’s Encounter of Leo the Great with Attila. The pope meets the invader. Tradition adds Peter and Paul above as enforcers. Attila turns back. Watch calm authority push fear off the field.

Eighteenth is Fire in the Borgo from Raphael’s school. A legend of a papal blessing stopping flames becomes a showcase for bodies. After the Sistine unveiling, everyone drew muscles; here, the students try to match the master and overshoot. You see the impact in real time.

Nineteenth is Guido Reni’s Crucifixion of St. Peter in the Pinacoteca. No background, just black. Laboring men, a straining saint, an upside-down cross. Expression is minimal. The fact of it carries the weight.

Twentieth is Nicolas Poussin’s Martyrdom of St. Erasmus. A Roman capstan winds out entrails as the pagan priest points to Hercules and angels arrive with palms and crowns. The blue, white, and red blaze like a warning. It’s baroque and controlled at once.

Twenty-first is Guido Reni’s St. Matthew. A quiet gaze shared with an angel. No speech, no miracle, just attention. The realism of hair, veins, and age tells you the baroque has arrived.

Twenty-second is Donato Creti’s Astronomical Observations. Eight canvases of the known heavens, with telescopes and eighteenth-century onlookers. They helped argue for an observatory. Saturn already has rings. You’re looking at curiosity becoming infrastructure.

Twenty-third is Wenzel Peter’s Adam and Eve in Eden. A devout menagerie. Over two hundred animals painted with near-photographic care, living in harmony with two modest humans. It’s a theology of peace disguised as a nature painting.

Twenty-fourth is the Apoxyomenos, a Roman copy after Lysippus. An athlete scrapes oil and dust from his skin. One foot lifts. One arm reaches out. Greek motion translated into Roman marble, then into your sense of balance.

Twenty-fifth is the Bronze Hercules. Gilded, watchful, with lion skin, club, and the apples of the Hesperides. It was buried after lightning struck it, with a carved F C S to mark the rite. Survival like this is rare; bronze was usually melted for reuse.

Twenty-sixth is the Colossal Head of Augustus. Young, composed, and larger than life in the courtyard. The face is propaganda that’s still working two millennia later.

Twenty-seventh is the Sarcophagus of Saint Helena, Constantine’s mother, carved from imperial porphyry. Military scenes on a woman’s tomb hint it was reused. Her role in marking Christ’s tomb gives the red stone a sharper edge.

Twenty-eighth is the Artemis of Ephesus in the Candelabra Gallery. People call them many-breasted at a glance. They’re bull testicles, fertility as a blunt symbol. It’s Roman copying of an Asian cult image, and the shock has not aged.

Twenty-ninth is the Resurrection of Christ tapestry in the Gallery of Tapestries. Flemish work after Raphael’s designs, once hung in the Sistine. Walk and watch the eyes of Christ follow you. It’s a simple device with a clear message.

Thirtieth is the Spiral Staircase by Giuseppe Momo. A 1932 double helix for crowd control that feels timeless. One spiral up, one down. You’ll remember the ride as much as the view.

Now, how do you see this without drowning in it? Start at the Pinacoteca for Raphael, Caravaggio, Guido Reni, Poussin, and Leonardo while your mind is fresh, then move to the classical sculpture courts, then the Raphael Rooms, and finish with the Sistine. Save St. Peter’s for last.

When you enter the Sistine, don’t stop under the Creation of Adam. Walk to the far wall first, turn, and let the whole ceiling read left to right. Then pivot to the Last Judgement. You’ll feel the arc from creation to judgment as a single thought.

In the Gallery of Maps, find Sicily. The cities are upside down on purpose; the map is oriented as if viewed from Rome. Then check Lazio to spot St. Peter’s without its future square. Bernini hadn’t drawn the embrace yet.

In the Room of Heliodorus, look for how Raphael paints light as theology. Angel light frees Peter. Heavenly light backs Leo against Attila. Human power is never enough on its own. That’s the argument.

In the Pio-Clementino, stand between the Laocoön, the Apollo, and the Torso. This is the triangle that trained Raphael and Michelangelo. You can trace a line from ancient muscle to Renaissance paint and back again.

In the Pinacoteca, take note of how quickly the centuries flip. From Raphael’s ideal beauty to Caravaggio’s raw truth in a few steps. That whiplash is the story of Italian art in the 1500s.

In St. Peter’s, let the Baldacchino guide your eye into the dome. Then step to the right side aisle for the Pietà. Give it a minute. The crowd thins if you don’t rush.

Outside, the square is a stage set for the Church’s public face. The obelisk predates Christianity by a thousand years; Bernini’s colonnade makes it feel adopted. Old power, new meaning.

If you only had an hour, I’d pick the Sistine Ceiling, the Last Judgement, the School of Athens, the Pietà, and the Laocoön. That’s the Vatican’s core argument: creation, judgment, reason, mercy, and warning.

If you have more time, add the Baldacchino, Handing Over the Keys, Transfiguration, and the Gallery of Maps. You’ll get theology, politics, painting, and space in balance.

The order matters because your energy and attention are finite. Front-load what changes how you think; back-load what’s delightful. That’s why Momo’s staircase is last, it’s a graceful exit.

What ties all of this together isn’t just skill. It’s a set of claims about God, man, time, and power, laid in stone, pigment, and bronze. The Vatican is a debate you can walk through.

And walking through it, ranked like this, gives you a narrative spine. You start with creation, end with ascent, and hold the best in view while the rest supports it.

That’s the point of a guide like this. To make choices, not hedge. It can be difficult to navigate when the world offers you a maze.

Take this ranking, adjust one or two if you must, and then test it with your own eyes. Art is an argument. Make yours standing in front of the work, not in a souvenir shop.

When you’re done, you’ll know why the first sentence here was so direct. Beauty isn’t a side dish in the Vatican. It’s the logic of the place.

And if you leave with one conviction, let it be this: the greatest works don’t just show you something, they change how you look at everything else.

Reminder: What you’re reading is just a teaser. The real deep dives live behind the paywall.

Support our work and unlock the full experience for just a few dollars a month. As a premium member, you’ll get:

Full-length deep-dive essays delivered every weekend

Complete access to the archive of art, literature, and philosophy breakdowns

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

Join today and never miss the stories, insights, and beauty that others overlook.

Today, meaning often collapses into utility, but the Vatican confronts you with a different logic.

Form and matter reconciled.

The verdict you feel isn’t opinion but recognition that reality is MEANT TO shine with beauty.

I was there last week. Should have seen this post before I went. Just saw an overload of beautiful paintings, without knowing what was portrayed. Split second attention for every painting because it was just too much.