What Awaits Us After We Die

Why humanity’s oldest stories of paradise, punishment, and rebirth still shape how we live today.

The idea of death frightens many, but what truly shapes human behavior isn’t the fact of dying. It’s what we believe comes after. Heaven, hell, and reincarnation are maps we carry in our minds, guiding how we live, love, and judge ourselves. That’s why when you look closely at the three largest religions Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism you not only find different stories about the afterlife, but you also find different visions of what it means to be human.

For most of history, people didn’t see death as an end. It was a threshold. What lay beyond depended on what you believed and how you lived. The churchyard in Christian villages wasn’t just a burial ground; it was a reminder that the soul had a destiny. In Muslim communities, the grave was the first step toward the Day of Judgment. And in Hindu towns, death was a turning of the wheel, not its stopping. The afterlife shaped daily choices long before modern notions of psychology or ethics existed.

Let’s start with Christianity. Heaven and hell are the two pillars of the Christian afterlife. These aren’t abstract metaphors in Christian teaching. Christians describe heaven as an actual place, a realm of joy in the presence of God. “In my Father’s house are many rooms,” says the Gospel of John. It’s imagined as a reunion with loved ones and with the divine, where suffering is no more. Hell is not a vague darkness. It’s defined as eternal separation from God, a consequence, not a random punishment.

That simple belief shaped how millions lived. Medieval Christians gave land to churches and built hospitals not only out of compassion but because they believed good deeds could tip the scale of judgment. Eternity mattered. Salvation was the central drama of life, and the church was its stage. Judgment wasn’t distant; it was the quiet companion of every moral decision.

Christian theology added something powerful: resurrection. Unlike reincarnation, resurrection is a one-time transformation. The body rises, not as it was, but glorified. Death isn’t a recycling loop but a bridge to a final state. The early church used this belief to give persecuted communities hope. Rome could kill your body, but not your soul. The grave was temporary.

Hell, as preached from pulpits, carried weight not because it was fiery, but because it was final. Eternal separation. No second chances. That finality gave Christian morality its edge. People feared hell, yes, but they also longed for heaven. The two worked like opposite poles of a magnet, pulling believers toward what they thought mattered most.

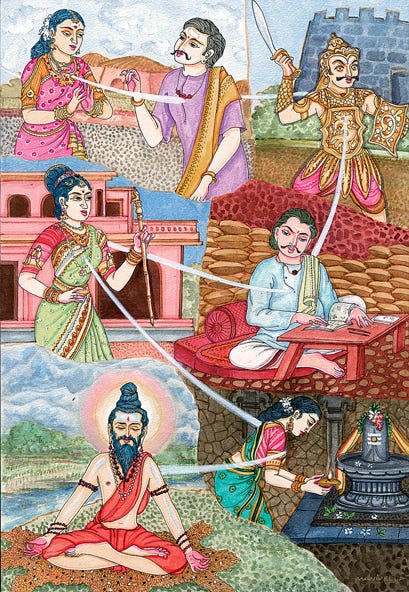

Then there’s Hinduism, a completely unique architecture of the soul. Instead of a single final judgment, Hindu belief sees existence as a cycle: birth, death, rebirth. Samsara is the wheel that keeps turning. The soul, or atman, doesn’t die. It travels. What shape it takes next depends on karma, the moral law of cause and effect. A life well-lived lifts you upward. A life spent in ignorance or cruelty drags you down.

This worldview builds patience into the fabric of belief. You don’t need to settle everything in one lifetime. Your deeds echo into the next. That’s why Hindu rituals around death are less about finality and more about transition. Funerals are reminders that the soul has begun another journey, not reached its end.

Karma isn’t a mystical ledger. It’s practical. Your actions ripple forward. They shape your future existence, just as the lives you lived before shaped them. That makes the moral universe feel immediate and personal. The gods aren’t punishing or rewarding at whim; you are.

At the heart of Hindu afterlife belief is moksha (liberation). Escape from the wheel. It’s the goal but not easily achieved. It demands knowledge, selflessness, and spiritual maturity. For some, it’s a long road of many lifetimes. For others, a flash of enlightenment can break the cycle.

Unlike Christianity, Hinduism doesn’t see heaven or hell as permanent. Swarga (heaven) is a reward, but temporary. Naraka (hell) is punishment, but also temporary. Both are waystations. The soul eventually returns to the cycle until it’s ready to transcend it. The moral universe is not about eternal separation but about learning, growing, and evolving.

This difference matters deeply. If you believe your soul lives many lives, urgency changes. Death isn’t the cliff edge of meaning; it’s a bend in the road. That creates a culture of spiritual endurance rather than final reckoning. The emphasis falls less on last-minute salvation and more on long-term harmony with dharma — cosmic order.

Now, Islam steps onto this landscape with its own clear voice. Like Christianity, it places history on a linear timeline: one life, one death, one judgment. But its eschatology is more vivid. The Qur’an paints paradise and hell in striking images. Gardens with rivers, flowing honey, shade, and companionship fill heaven, while fire, thirst, and isolation await those who reject the truth.

Islam teaches that the afterlife begins in the grave. The Day of Judgment isn’t metaphorical. It’s a promised event. God will resurrect all humans and weigh their deeds. Jannah (paradise) awaits the righteous; Jahannam (hell) the wicked. This judgment isn’t arbitrary. Everything a person does, no matter how small, gets recorded.

That belief has power. It gives daily choices eternal significance. A minor act of charity isn’t just good; it’s invested in your afterlife. A sin has consequences. The Qur’an’s language is direct: whoever does an atom’s weight of good will see it, and whoever does an atom’s weight of evil will see it.

Islam rejects reincarnation outright. It sees it as undermining divine justice. This life is a test, not a rehearsal. Paradise and hell are the outcomes, not temporary stops. That finality mirrors Christianity’s structure, but with a sharper emphasis on divine accountability.

Three faiths. Three visions. Now comes the part that matters most and that is what they reveal about us.