When Faith Spoke Greek: The Jewish–Greek Collision That Still Shapes Us

From the streets of Alexandria to the hills of Jerusalem, two worlds, one bound to God’s covenant, the other to the power of reason, left a legacy that decides how we pray, think, and fight over truth

Table of Contents

The Ancient Dialogue That Built the Modern Mind

How the Septuagint Canon Changed Scripture Forever

Architecture - Rumbach Street Synagogue

The Ancient Dialogue That Built the Modern Mind

When the God of Israel met the mind of Greece, the collision sparked revolts, conversions, and ideas so powerful that they still decide how we think, believe, and fight over truth today.

The BlackWolf

When talking about the modern Western culture, few threads are as influential as those woven by Jewish and Greek cultures. The Hebrews, rooted in monotheistic faith and covenantal law, and the Greeks, initially champions of polytheistic myth and then of Jesus Christ, always marked with philosophical inquiry, seem at first glance to be worlds apart.

Yet, their interactions, marked by both collaboration and conflict, shaped the intellectual and spiritual foundations of the modern world. How did these two cultures, one grounded in divine revelation and the other in human reason, influence each other?

The story of Jewish and Greek cultural interaction begins in earnest with the conquests of Alexander the Great (333 BC). Before this, Hebrew culture thrived in the ancient Near East, centered on the monotheistic worship of Yahweh and the Torah, the sacred text codifying laws and narratives by the 5th century BC.

The Hebrews, descendants of the Israelites, navigated periods of independence (e.g., the Kingdom of Judah) and exile (e.g., the Babylonian Exile, 586–539 BCE), forging a resilient identity tied to their covenant with God.

Meanwhile, Greek culture flourished in the Aegean, with city-states and kingdoms like Athens, Sparta and then Epirus and Macedonia cultivating polytheistic religion, epic poetry (Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey), and early philosophy (Thales, Pythagoras). Direct contact was limited, though trade routes, such as those of the Phoenicians, allowed indirect exchanges of goods and ideas.

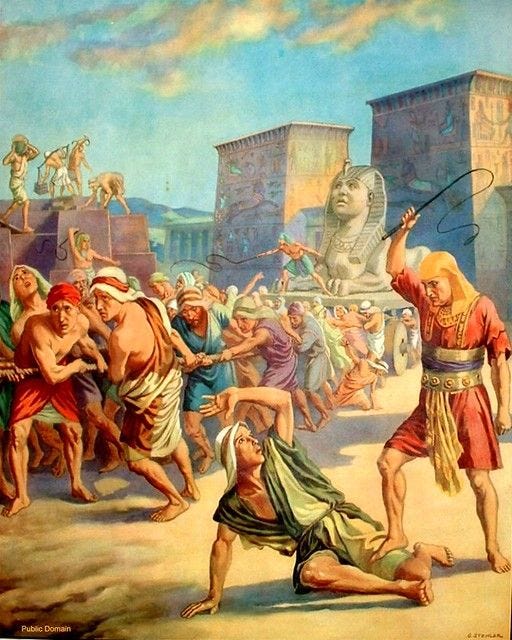

Alexander’s empire changed everything. By 333 BC, his conquests swept across the Near East, including Judea, spreading Greek language, customs, and thought, a process known as Hellenization.

After his death in 323 BC, his generals, the Diadochi, divided the empire, with the Seleucids and Ptolemies ruling over Jewish populations. This era saw both cultural synthesis and resistance. In Alexandria, a thriving Jewish diaspora produced the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (~3rd century BC), making Jewish scriptures accessible to Greek-speaking audiences and blending linguistic traditions.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BC–50 AD) later harmonized Greek philosophy, particularly Plato’s ideas of the eternal and Stoic ethics, with Jewish theology, arguing that the Torah’s wisdom aligned with universal truths.

Yet, Hellenization also sparked conflict. The Seleucid king Antiochus IV (r. 175–164 BC) imposed Greek practices, such as banning circumcision and defiling the Jerusalem Temple with pagan altars. Many Jews welcomed the new culture while others fiercely opposed it.

This provoked the Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BC), a fierce Jewish uprising that restored traditional worship and inspired the festival of Hanukkah.

The revolt underscores a key tension: while some Jews embraced Greek culture, others saw it as a threat to their monotheistic identity.

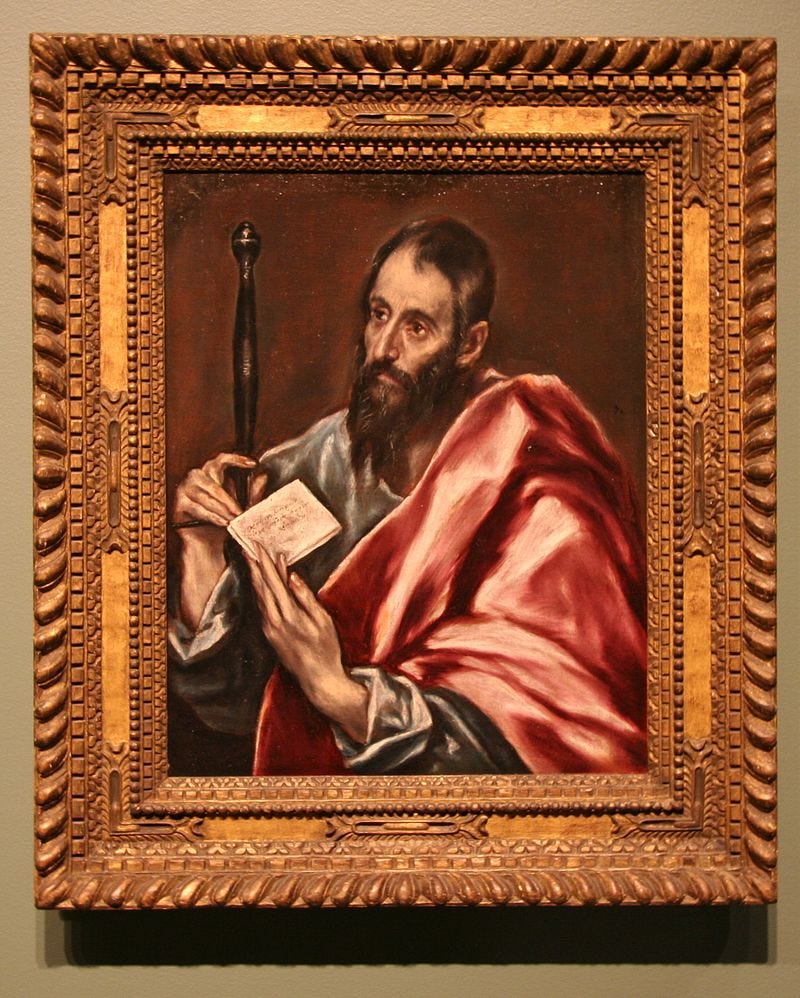

Under Roman rule, interactions continued within a shared imperial framework. Jewish communities in Greek-speaking cities like Alexandria faced tensions, as seen in anti-Jewish riots (38–41 AD). However, the rise of Christianity, born from Jewish roots and spread through the Hellenic world, became a bridge between the two cultures.

Early Christian thinkers adopted Greek philosophical concepts, such as the Logos (divine reason) in the Gospel of John, to articulate their theology. This synthesis laid the groundwork for Western thought, blending Jewish monotheism with Greek rationalism.

The evolution of Greek culture through Christianity and the Byzantine Empire (330–1453 AD) marked a new chapter. After Emperor Constantine established Constantinople in 330 AD, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire became a crucible for Greek culture’s transformation. Christianity, now the state religion, reshaped Greek traditions.

Pagan temples were replaced by churches, and Greek philosophy was repurposed to serve Christian theology. Figures like the Cappadocian Fathers (e.g., Gregory of Nyssa, 4th century) used Plato and Aristotle to articulate doctrines like the Trinity, echoing Philo’s earlier synthesis.

Byzantine scholars preserved Greek texts, from Homer to Plato, in monasteries, ensuring their survival through the Middle Ages. Byzantium welcomed the Jews when they were expelled from Spain, establishing new communities.

These communities continued to interact with the evolving Greek culture. Jewish scholars in cities like Thessaloniki engaged with Greek intellectual traditions, translating texts and contributing to philosophical discourse.

The Byzantine synthesis of Greek and Christian elements influenced Jewish thought, particularly in mystical traditions like Kabbalah, which absorbed Neoplatonic ideas about divine emanations.

Despite their differences, Jewish and Greek cultures shared surprising commonalities. Both placed immense value on wisdom and inquiry. Hebrew wisdom literature, such as Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, explores ethical living and the human condition, much like Greek philosophical dialogues by Plato or Aristotle. For instance, Proverbs’ call to “get wisdom, get understanding” (4:5) echoes Socrates’ emphasis on self-knowledge.

Both cultures saw wisdom as a path to moral and societal harmony. Community was another shared pillar. For the Hebrews, the covenant with God bound the nation as a chosen people, with communal laws (e.g., Sabbath observance) reinforcing collective identity.

Similarly, Greek city-states fostered civic pride, with Athens’ democratic assemblies and Sparta’s militarized society emphasizing duty to the polis. Later, the Greeks also believed they were the chosen people by Christ, which made it easy for them to embrace Christianity.

Both cultures, in their own ways, prioritized the collective over the individual, whether through divine law or civic participation.

Narrative also united them. The Hebrews used historical-theological stories, like the Exodus, to transmit values of liberation and faith. The Greeks relied on myths, such as Odysseus’ journey, to explore heroism and human struggle. While their purposes differed—Hebrew narratives pointed to divine purpose, Greek myths to human potential—both cultures used storytelling to define identity and morality.

For all their similarities, the two cultures diverged profoundly in religion, worldview, and cultural expression. Hebrew culture was anchored in strict monotheism, worshipping a single, transcendent God without physical form. The Torah’s commandments, such as the prohibition on graven images, shaped a faith centered on ethical conduct and covenantal loyalty.

Greek religion, by contrast, was polytheistic, with anthropomorphic gods like Zeus and Athena celebrated through rituals, oracles, and temple statues. Where Hebrews sought divine will, Greeks pursued human excellence (arete) and harmony with the cosmos.

Their worldviews reflected these religious differences. Hebrew thought viewed history as linear, moving toward redemption or judgment under God’s plan. The Book of Isaiah, for example, envisions a messianic future.

Greek thought, influenced by philosophers like Heraclitus, often saw time as cyclical, with no ultimate divine purpose but a focus on understanding the natural order. This contrast fueled tensions during Hellenization, as Greek emphasis on human reason clashed with Jewish fidelity to divine law.

Cultural output further distinguished them. Hebrew culture prioritized religious texts, producing the Torah, Prophets, and later the Talmud, with minimal visual art due to aniconic traditions. Greek culture, however, excelled in sculpture (e.g., the Parthenon friezes), architecture (e.g., temples), and theater (Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Aristophanes’ comedies).

While Jewish synagogues were places of study and prayer, Greek theaters and gymnasia celebrated human creativity and physicality. These differences underscored the Jewish resistance to Greek cultural practices, such as public nudity in gymnasia, seen as incompatible with modesty laws.

The encounter between Jewish and Greek cultures, evolving through Christianity and Byzantium, was a dynamic interplay of synthesis and tension. From the Septuagint’s translation to the Maccabean resistance and Byzantine theological debates, their dialogue forged a rich legacy. They shared a commitment to wisdom, community, and narrative, yet diverged in faith, worldview, and expression.

Byzantium transformed Greek culture into a Christian framework, preserving its intellectual heritage while engaging Jewish communities in a complex dance of coexistence. This ancient conversation, rooted in Jerusalem and Athens and refined in Constantinople, offers a mirror for our own cultural debates, where faith and reason continue to seek harmony.

Art - Hellenistic Jewish Art

Book Corner

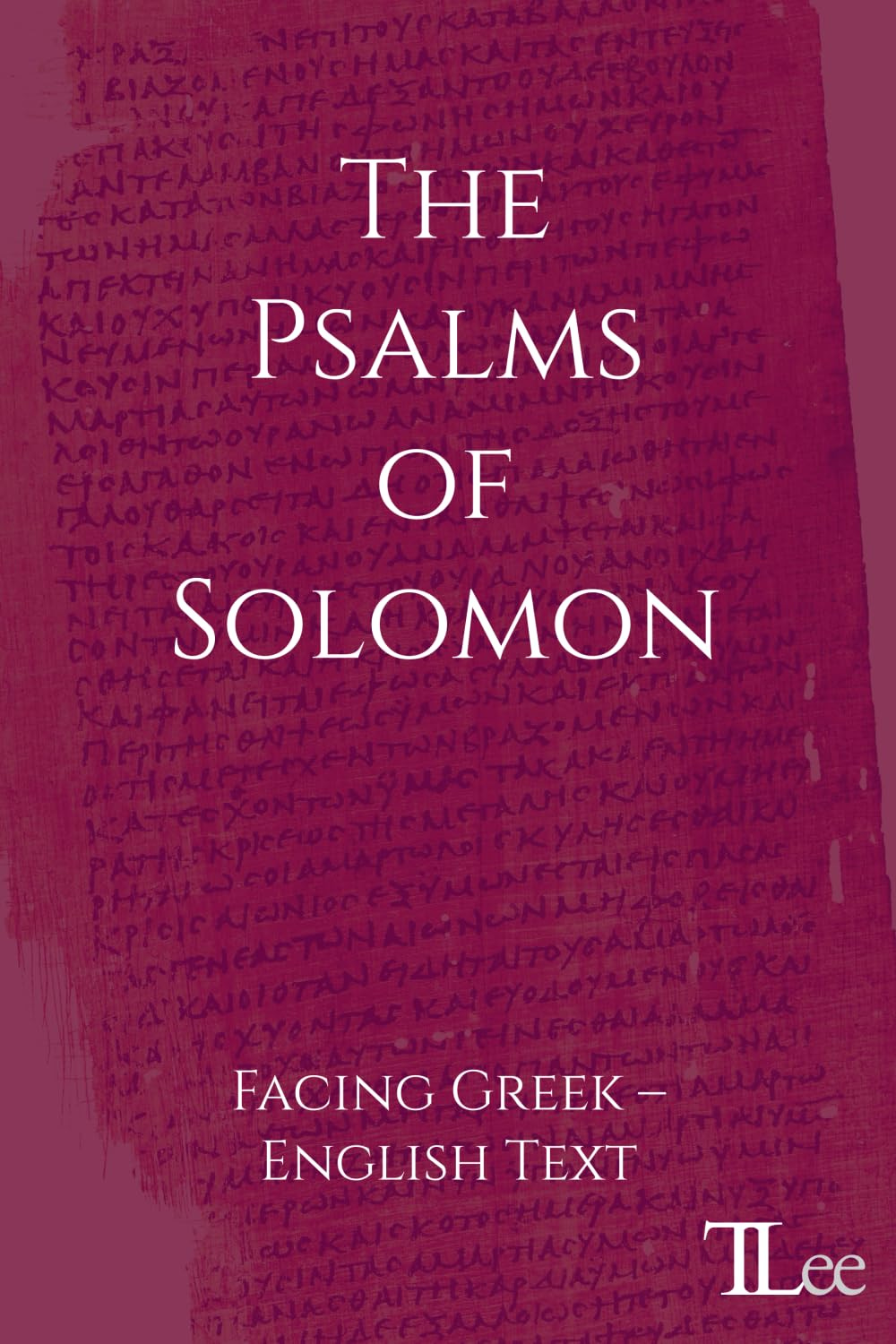

The Psalms of Solomon are a set of early Jewish writings responding to the Roman conquest of Judea in 63 BCE, depicting divine judgment on Jerusalem’s sins, the eventual judgment of Rome, and hope in a coming Davidic Messiah. They hold historical, theological, and eschatological value, addressing themes of resurrection, destruction, and messianism rare in pre-Christian Jewish literature. This parallel edition, with original languages and English translation, offers an accessible resource that sheds light on early Jewish thought, corrects misconceptions about Judaism, and reveals texts influential on early Christian writings.

From Ideas to Influence

You’ve got stories, insights, and ideas worth sharing. But turning them into posts, articles, or threads that people actually read? That takes time and a lot of it.

I take your raw thoughts, voice notes, or half-finished drafts and turn them into content that sounds like you on your best day. No generic fluff. No “that doesn’t sound like me” moments. Just words that make your audience stop scrolling and pay attention.

You focus on what you do best. I’ll handle the writing. Let’s talk → admin@thecultureexplorer.com.

How the Septuagint Canon Changed Scripture Forever

Fourth-century Christians opened their Bibles and found books no synagogue in Jerusalem had ever called Scripture. They weren’t forgeries. They weren’t new. They were Jewish and they came from a Greek Bible that would change the faith of millions.

By Culture Explorer

Some of the earliest Christian Bibles contained books the Hebrew Bible never had. That’s a clue to one of the most fascinating cultural handoffs in history, where Jewish tradition and Greek language combined to create a library that would influence Christianity for centuries.

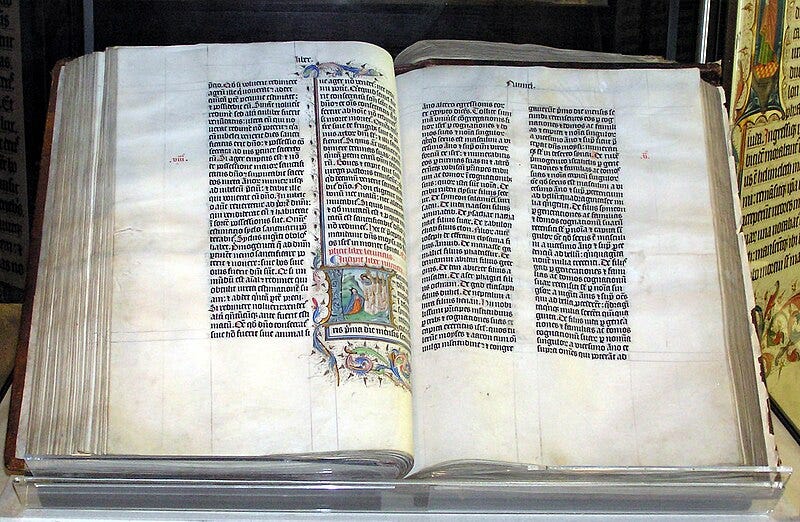

Imagine opening a Bible in the fourth century. Alongside Genesis, Isaiah, and the Psalms, you’d find Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, and Ben Sira. These weren’t fringe works. They sat in the same volume as the Law and the Prophets, read in churches, shaping sermons and theology. Yet no Jewish synagogue in the rabbinic tradition recognized them as Scripture. So how did they get there?

These books were part of what scholars call the Septuagint canon, a Greek collection of Jewish writings that went beyond the Hebrew Bible (sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy). The puzzle is old: did Christians create this expanded canon, or did they inherit it from Jews who used Greek in the centuries before Christ?