When Wonder Ruled the World and 20 That Defined the Age of Spectacle

20 Baroque wonders that defined the age of spectacle

A pie split open.

Not with meat, but with a living blue sheep crowned with golden horns. Moments later, a dwarf and a giant fought for the crowd, while lions prowled and automata stirred in a man-made forest. At the center of it all rose a statue of Constantinople, guarded by a real lion with the motto, “Don’t touch my lady.”

This was not a carnival. It was statecraft. In 1454, Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy staged the “Feast of the Pheasant” to shock Europe’s nobility into joining a crusade against the Turks. He wielded wonder as a weapon.

For one night, it worked. Hardened knights swore vows “struck with wonder.” Philip looked like a new Alexander, ready to reclaim the East. By morning, the spell was broken. The crusade never left the banquet hall.

That moment captures the double edge of wonder. For centuries, marvels such as strange births, exotic beasts, dazzling automata, had the power to inspire loyalty, shape belief, and even launch new sciences. But they also carried fragility. Wonder could bind, but the spectacle could also collapse once people exposed it as smoke.

In medieval Europe, wonder defined what people thought was worth knowing. Bestiaries brimmed with manticores, unicorns, and dog-headed men. Travelers returning from Asia described the machines of Byzantium, crocodiles hanging in Egyptian churches, and springs with healing powers.

Clerics gave it theological force. Augustine taught that everything, from fire to stone, was wondrous because all depended directly on God’s will. To live without wonder was to ignore divinity.

Aristotelians pushed back. For them, philosophy meant causes and universals. Marvels such as two-headed calves, fiery stones, monstrous births were curiosities unworthy of serious study. Wonder, they said, was ignorance in disguise.

But the culture beyond universities couldn’t resist. Wonders traveled by manuscript, sermon, and rumor. They shaped how people imagined the world and their place in it.

By the fifteenth century, a new category emerged: the preternatural. Neither natural nor miraculous, it included the oddities that fascinated but didn’t fit. Physicians led the way.

Girolamo Cardano chronicled bizarre illnesses. Giovanni Battista della Porta experimented with strange plants and optical tricks. Paracelsus claimed monstrous births revealed hidden truths about nature. These men turned marvels into case studies.

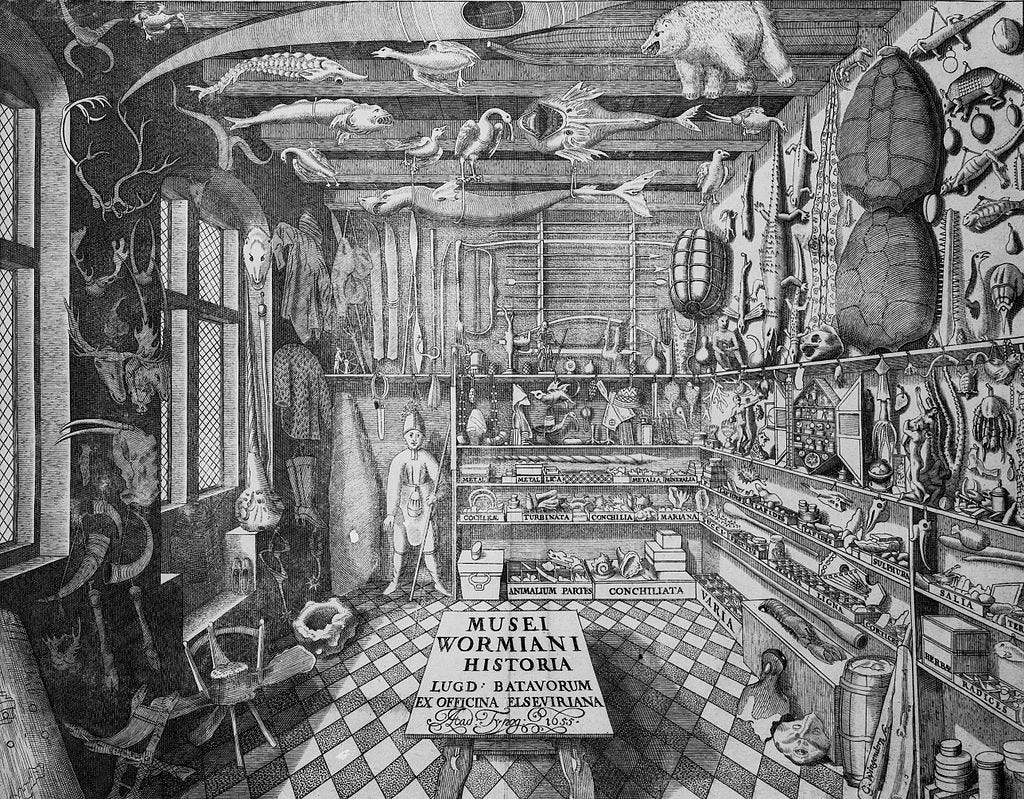

Cabinets of curiosity became their stages. In Copenhagen, Ole Worm displayed narwhal tusks as unicorn horns. In Rome, Athanasius Kircher’s museum featured fossils, Egyptian mummies, mechanical birds, and “talking statues.” The cabinets blurred science, spectacle, and power.

Printed broadsheets amplified the craze. Engravings of monstrous births and dragons spread across Europe. They were not mocked as fantasy but treated as records, visual evidence of nature’s excesses.

The Jesuits perfected wonder as pedagogy. Their colleges staged plays filled with pyrotechnics and machinery. Their missions shipped back crocodiles, shells, and plants from the New World. Kircher, the Jesuit polymath, turned Rome’s Collegio Romano into a factory of marvels, where automata performed alongside cosmic maps.

Baroque Europe went further. Andrea Pozzo’s ceiling in Sant’Ignazio dissolved into a painted sky, tricking the eye into endless space. Courts staged festivals with mechanical elephants, pyres bursting into flame, and allegories of conquest. Wonder was no longer a curiosity; it was a system of control.

To dazzle was to dominate. Marvels became instruments of obedience.

Francis Bacon urged philosophers to collect “instances of the strange” as the foundation of knowledge. René Descartes tried to explain marvels universally, stripping them of mystery but not denying their importance.

Robert Boyle transformed marvels into “matters of fact.” The Royal Society filled its Philosophical Transactions with strange births, odd stones, and reports of comets. The bizarre was not banished, it became data.

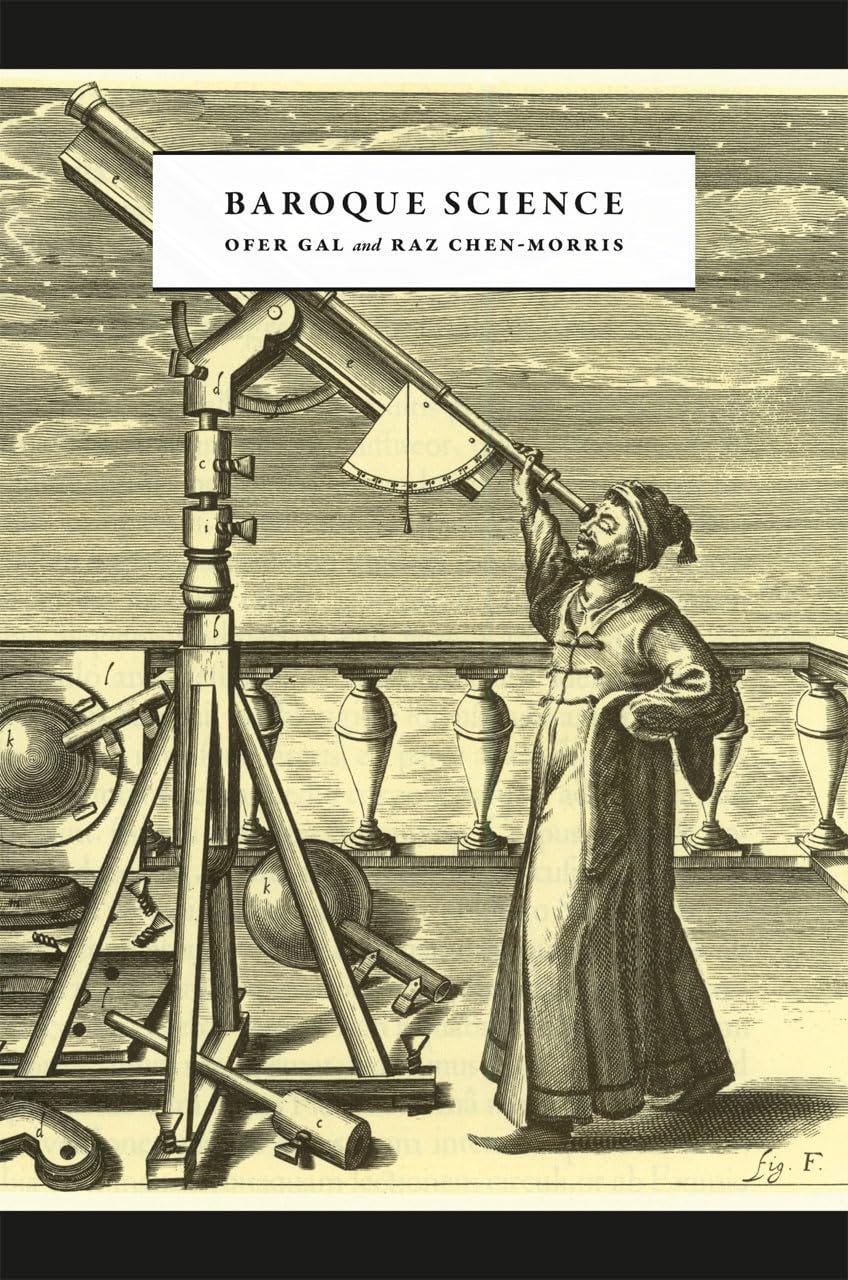

Even Galileo understood the power. He presented his telescope to the Medici not as a tool, but as a marvel: an instrument that revealed moons circling Jupiter and craters on the Moon. It was both science and spectacle, worthy of princes.

For a brief moment, science and wonder overlapped seamlessly. Cabinets of curiosity doubled as laboratories. What once was gossip became evidence.

But abundance eroded prestige. Unicorn horns were traded in elite markets, automata filled noble gardens, and marvels risked becoming mere toys.

Critics sharpened their knives. Gabriel Naudé dismissed wonders as impostures of religion. Giulio Cesare Vanini tried to naturalize miracles and burned at the stake in 1619. By 1700, David Hume declared wonder the emotion of the unlettered. Fontenelle mocked marvels in France.

The cultural tide flipped. What once marked elite status now smelled of vulgarity. To marvel was to expose oneself to ridicule.

Architecture reflected the change. Baroque ceilings dissolved into heaven; Neoclassicism returned to sober lines. Medicine reclassified monstrous births as defects of embryology. Marvels lost their aura.

By the mid-eighteenth century, monsters were no longer jokes of nature but deviations from its laws. The proper response was not awe but distaste.

The decline of wonder was not the triumph of science over superstition. Medieval philosophers had often been more skeptical than seventeenth-century naturalists. What killed wonder was taste, not truth. Snobbery did what philosophy and theology had failed to achieve.

The Enlightenment claimed order, reason, and uniformity. Marvels became vulgar. The very passion that once propelled inquiry was exiled to fairs, novels, and children’s tales.

And yet, wonder never truly vanished. Museums that trace their lineage to cabinets of curiosity still draw crowds with dinosaur bones and Egyptian mummies. Tourists still flock to illusionistic churches, not for doctrine, but for awe.

Wonder changes costume. It moves from court to science, from science to popular culture. But it never dies.

Perhaps that is the lesson Duke Philip’s failed crusade offers us. Wonder can inspire, manipulate, and even give birth to knowledge. But it cannot be contained. When it loses its prestige in one realm, it erupts in another.

Today, in an age obsessed with certainty, perhaps what we lack is not more knowledge but more wonder.

The Baroque age didn’t just use wonder, it perfected it. Churches became illusions of heaven, palaces turned into theaters of power, and entire cities were redesigned to overwhelm the senses.

But here’s the thing: most people only know the big names… Versailles, St. Peter’s, maybe the Trevi Fountain. The true Baroque wonders are scattered across Europe, the Americas, and even Asia. They’re stranger, bolder, and in many ways more breathtaking.

I’ve pulled together a special list for Founders: 20 Baroque wonders that defined the age of spectacle. These are places and creations where faith, politics, and art collided to create beauty so intense it still stuns visitors today.

1. San Carlo al Corso, Rome (1612–1672)

This Jesuit church stretches like a stage set in stone. Its vast nave and frescoes made worshippers feel swallowed by grandeur, reminding them that faith was not private—it was cosmic.

2. Palazzo Barberini Ceiling by Pietro da Cortona, Rome (1633–1639)

The fresco Triumph of Divine Providence bursts across the vault. Allegories of papal power float among the clouds, reminding every visitor that the Barberini family’s rule was sanctified from above.

3. Church of the Gesù, Rome (ceiling completed 1679)

The Jesuits’ mother church pioneered Baroque illusion. Baciccio’s fresco makes the ceiling dissolve as saints tumble into heaven. To stand there is to feel the boundaries of earth and sky collapse.

4. Cappella Palatina, Palermo (Baroque refurbishments, 1600s)

Originally Norman-Byzantine, the chapel gained Baroque stucco overlays that shimmer with gold. It’s a rare hybrid: medieval mosaics glowing beneath layers of theatrical Baroque ornament.

5. Sanctuary of Loyola, Spain (1689–1738)

Built at the birthplace of Ignatius Loyola, this vast complex blends pilgrimage with imperial architecture. Its domed basilica declares the Jesuits not just as teachers, but as masters of spectacle.

The Baroque wasn’t about restraint. It was about overwhelming you… body, mind, and soul. Behind gilded altars and painted ceilings was a deliberate attempt to stun, to move you closer to God, or to make you bow before power.

The private tour continues with another fifteen Baroque wonders after the paywall.

![Triumph of Bacchus and Adriane (part of The Loves of the Gods); by Annibale Carracci; c.1597–1600; fresco; length (gallery): 20.2 m; Palazzo Farnese, Rome[104] Triumph of Bacchus and Adriane (part of The Loves of the Gods); by Annibale Carracci; c.1597–1600; fresco; length (gallery): 20.2 m; Palazzo Farnese, Rome[104]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ioav!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2709edfa-a4f2-4a6f-b5b0-bb0b29cceb9d_1024x527.jpeg)