Who am I?

The First Rebellion Was Inward

Of all the stories humanity has told, few are as quietly explosive as the one hidden inside The Upanishads. It isn’t about empires or revolutions. It’s about a group of people who walked out of the world we know, not to escape it, but to look reality straight in the face. They weren’t chasing wealth or power. They were chasing the question that eventually finds everyone: Who am I?

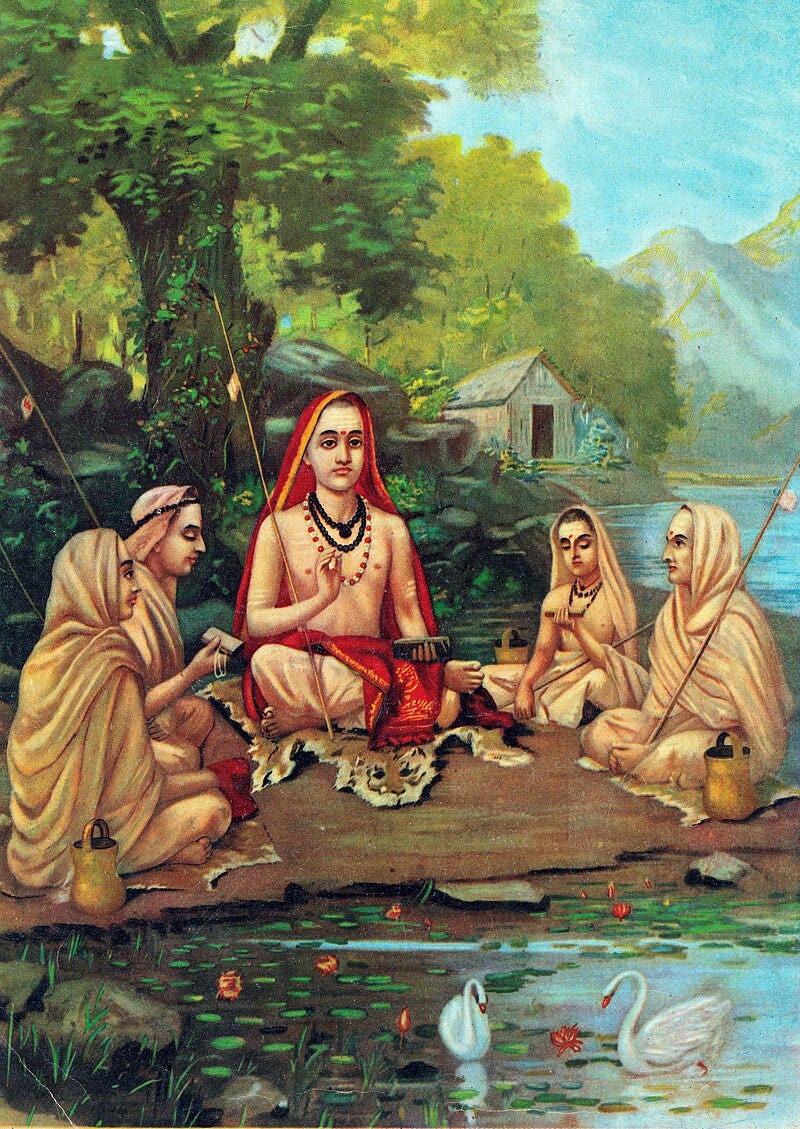

These seers didn’t write manifestos. They left fragments… conversations whispered along riverbanks, questions asked by teenagers and answered by Death itself, images so strange yet familiar that they land like sparks even today. Their words became the Upanishads, dispatches from those who dared to explore the mind with the same intensity explorers once gave to oceans. Far from royal courts and ritual fires, they gathered in forest academies. They questioned everything. They stripped away titles, memories, identities — everything — until only the raw pulse of awareness remained. Their rebellion was quiet but seismic: they believed no priest or ritual stood between a person and truth. Anyone could step through that door. You didn’t need a temple. You didn’t need permission. All you needed was the courage to walk inward.

In the Vedic world, religion revolved around fire altars, hymns, and gods of thunder, wind, and sun. The sages of the Upanishads turned their gaze inward. They asked not about the gods, but about the one who perceives the gods. Who breathes, sees, and hears? Who is the witness behind the witness? The shift from external ritual to internal inquiry changed the spiritual DNA of an entire civilization. Where the Vedas worshipped the sun, the Upanishads asked, “Who is watching the sunrise?” The answers they found reshaped the world.

Their language introduced concepts that would echo through philosophy for millennia. They spoke of Brahman, the infinite ground of reality, not a deity with a face or a mood but the essence of existence itself… formless, vast, beyond comprehension. Within each human being they found Atman, the Self, the innermost awareness. Their most astonishing claim was simple and radical: Atman and Brahman are one. The infinite outside and the infinite inside are not two. This wasn’t theory to them; it was a discovery reached through relentless inner discipline. Their method wasn’t ritual but training the mind with the precision of a blade.

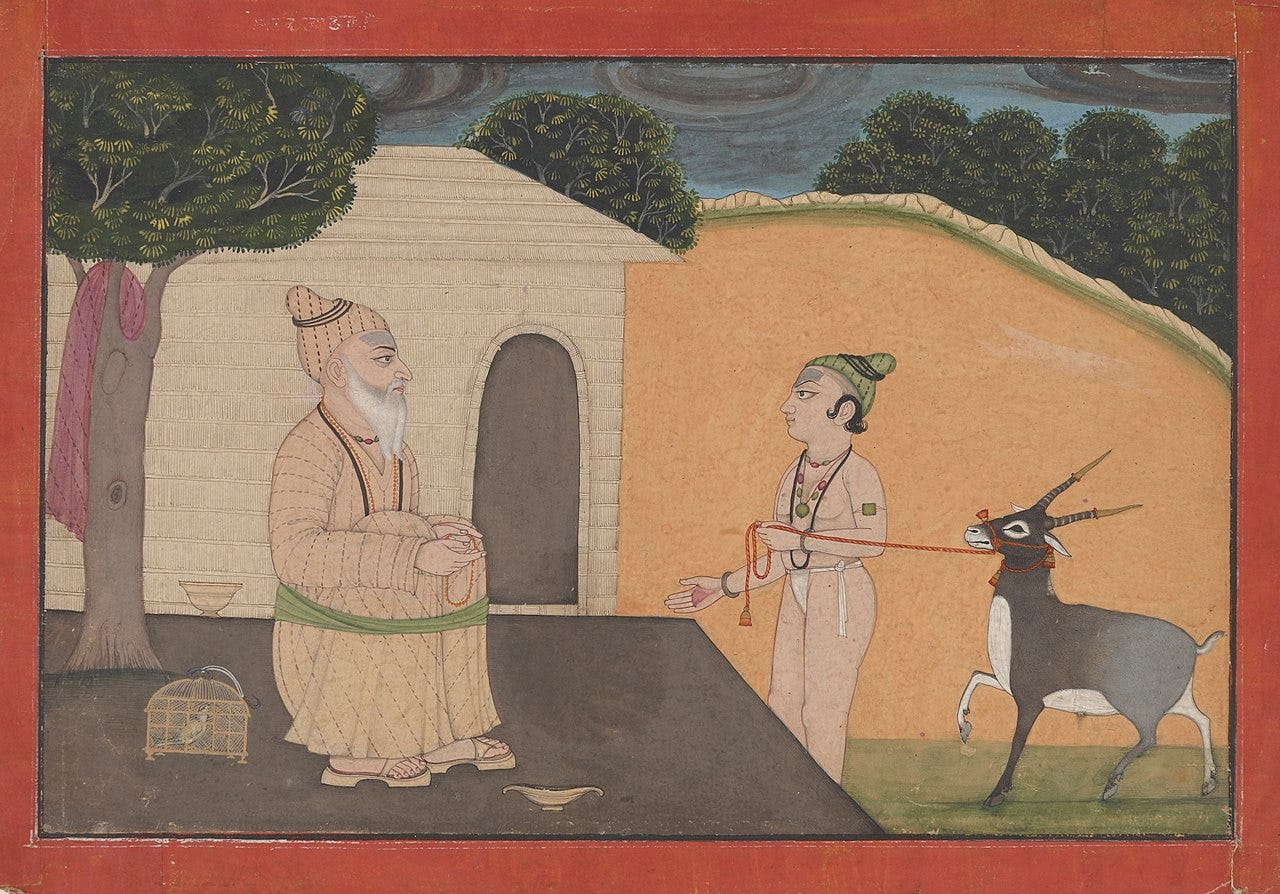

Their students lived in the forest for years, sometimes more than a decade. They learned to discipline attention with the same ferocity as a warrior trains with a sword. Meditation was not relaxation; it was a razor’s edge. They believed they could observe the mind like a scientist observes nature, peeling away layers of sensation, thought, and identity to reach something irreducible. In one of the most famous passages, a sage declared: “You are what your deep, driving desire is. As your desire is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. As your deed is, so is your destiny.” This wasn’t an uplifting slogan. It was a map. Desire, when scattered, binds? Desire, when focused, liberates?

The Upanishads describe four states of consciousness: waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and something beyond all three — turiya. Turiya is not trance or escape but a state where awareness wakes up within silence itself, beneath thought and beneath identity. It is not a place to run to; it is the place one has never truly left. What’s remarkable is that their language reflects the structure of modern cosmology. They described reality before creation as formless, timeless, spaceless — a fullness without edges. Physicists now call it singularity. They called it Brahman.

The journey to that realization was dangerous and demanding. The sages compared it to walking on the edge of a razor. To confront one’s own mind without distraction is to face cliffs and storms that few can endure. That’s why they insisted on guides who had walked this terrain and returned. They trained students young, not to control them but to ignite their courage before the caution of age set in. In one story, a teenage boy named Nachiketa stands before Death itself, refusing every earthly temptation for truth. Death relents and teaches him what lies beyond life and time.

The sages also explored the landscape of dreams. They observed how fear in a dream can trigger the same physical reactions as fear in waking life. Dream and waking, they concluded, are made of the same fabric. Deep dreamless sleep revealed an even deeper clue: in that stillness, the mind folds into its source. To awaken within that stillness is to discover what one truly is. That state, they said, is not created; it’s uncovered. It’s always there, like a mountain under clouds. The clouds don’t define the mountain; they only obscure it.

Their vision of desire was equally bold. They didn’t condemn it as an enemy. They saw it as energy to be redirected. Rather than dispersing it through endless cravings, they gathered it into a single flame—the hunger to know. They called this fire tapas. When tapas is cultivated, it becomes tejas: radiant power, the kind that conquers the self, not others. Many of these sages came from warrior families. It took the same courage to master the mind as it did to ride into battle.

The culmination of their exploration was simple and devastatingly clear. When everything that can be stripped away is gone… the body, the mind, even the sense of “I”… what remains is pure consciousness, chit. It is not owned, not born, not destroyed. This is the Self. And that Self is Brahman. They encapsulated it in three words: Sat-Chit-Ananda—Being, Consciousness, Joy. Not ideas, but the foundation of reality itself.

This realization didn’t turn them into hermits detached from life. Many returned to the world, ruled kingdoms, raised families, and created art. But nothing owned them anymore. Freedom for them meant living in the world without being bound by it. They saw death not as an end but as a change of clothing. They considered desire not a trap but a current they could direct toward the infinite. And they saw God not as something distant, but as the innermost reality of every living being.

Today, thousands of years later, their words still stand like an unmovable mountain. Empires have come and gone, religions have risen and splintered, but these teachings endure because they are not tied to one culture or creed. They speak of something older than civilization: the human hunger to know what lies beyond the surface. They speak to the quiet moments when rituals no longer satisfy and distractions lose their grip, when a single, dangerous question arises like a spark in the dark: Who am I?

That question is where the Upanishads begin. And for those willing to follow it, it has no end.

The question “Who am I?” doesn’t just belong to the forests of ancient India. It appears across civilizations, faiths, and philosophies. Why does it keep resurfacing, and what does that tell us about human nature? More importantly, what can we do with it in our own lives today?

→ Continue to the Premium Edition to explore how this same inner journey appears in Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, yoga, and beyond—and how their wisdom can be lived, not just admired.