Why Humanity Kept Believing in Gods

Article 2 of The Arc of Belief and Meaning

After humans asked why anything exists, they began to ask what kind of power holds it together. Here begins the second article in the Arc of Belief and Meaning series…

For a long time, I assumed creation myths were little more than early attempts at science. Primitive explanations for the sun, the rain, the stars, and the seasons, composed before people had instruments or equations. The more I read these stories carefully, however, the less that explanation made sense. These texts were not trying to explain how matter behaves. They were trying to answer a far more urgent question: why does the world not fall apart?

For most of human history, life did not feel stable or predictable. Floods erased settlements. Storms destroyed harvests. Disease moved through families without warning. Death arrived early and often. The world was experienced not as a reliable system, but as something that could turn hostile at any moment.

Creation stories begin precisely there. Not with curiosity and order, but with fear and chaos. Nearly every civilization starts the same way: darkness, water, emptiness, noise, something formless that must be shaped before life can survive inside it.

What differs from culture to culture is how order is imagined emerging from it, and what kind of divine presence is required to sustain that order.

One of the oldest creation texts we possess comes from the Rigveda, composed in India more than three thousand years ago. In its most famous creation hymn, the Nasadiya Sukta, the poet does something that still surprises modern readers. He admits ignorance. He describes a time when there was neither existence nor non-existence, neither death nor immortality, when even the gods appear only later in the sequence. Then he asks, almost casually, whether anyone truly knows how creation happened, and suggests that perhaps even the highest god does not know. This is not the voice of a credulous mind. It is the voice of someone willing to say, “I don’t know.” In this early vision, the gods are not rulers who impose order from above. They arise alongside reality itself, linked to heat, breath, rhythm, and balance. Creation is a fragile and unresolved process.

When I turned to Mesopotamia, the mood changed completely. In the Enuma Elish, chaos is no longer mysterious. It is dangerous. The goddess Tiamat embodies formlessness itself, and order only comes into being when the god Marduk defeats her and constructs the universe from her body. The sky becomes a ceiling, the earth a floor, boundaries are fixed, and laws are imposed. This is creation as engineering. It also mirrors its world. Mesopotamian society was rigid, hierarchical, and constantly under threat from invasion and famine. Order had to be enforced. Even the gods had to reenact creation each year through ritual, as if chaos were always waiting to return. Civilization itself felt like a defensive structure built against collapse.

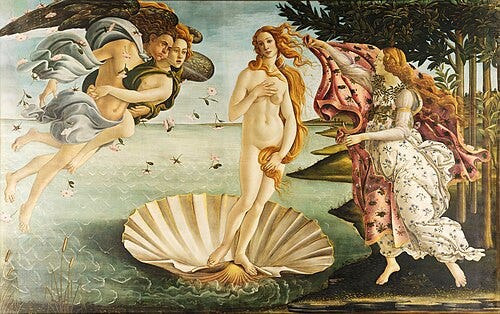

Greece shifts the story inward. In Hesiod’s Theogony, the gods are no longer distant forces or imperial rulers. They are recognizably human. Zeus fears being overthrown just as he overthrew his father. Hera plots. The gods lie, desire, rage, and make mistakes. Order still emerges from chaos, but now through family conflict rather than cosmic war. This is a psychological universe. The world makes sense because it behaves like people do. The gods are powerful, but not moral absolutes. They manage chaos rather than eliminate it.