Why the Uffizi Matters?

30 Masterpieces That Changed the World

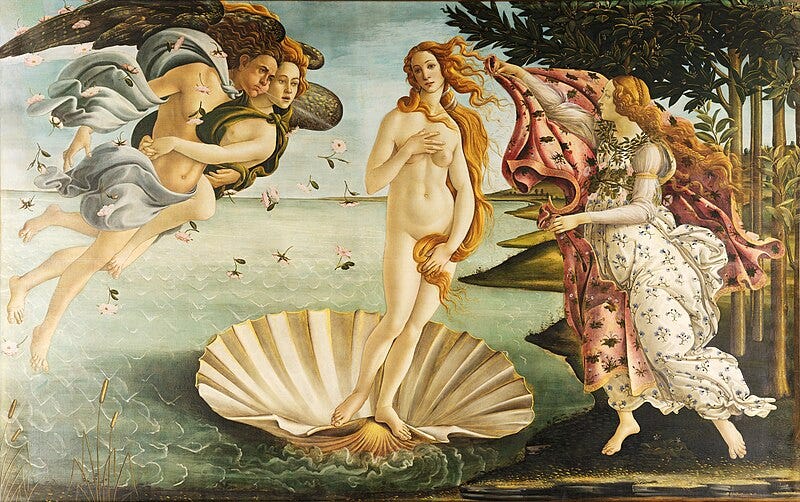

Everyone knows the Uffizi’s most famous painting… Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. She rises from the sea on her shell, fragile yet divine, carried by the wind and covered by a modest veil. Few images in history have defined beauty so completely.

Travelers from every continent line up just to see her. They take the photograph, post it online, and for many, that’s the Uffizi. But here’s the truth: the gallery is far more than one painting. It is where the entire story of Western art is told in a single sequence of rooms.

That’s why the Uffizi matters. It is not just Florence’s Museum. It is Western civilization’s memory palace. Without it, the Renaissance would feel scattered, the continuity of art broken.

The building itself carries that weight. Cosimo I de’ Medici built it in 1560 as offices—uffizi—to centralize power. His architect, Giorgio Vasari, also built the secret corridor stretching over the Arno, so the ruling family could walk above Florence unseen.

But Cosimo’s son, Francesco I, changed everything. He turned the top floor into a gallery for paintings, statues, and marvels. By 1591, guidebooks already called it one of the most beautiful sights in the world. The Uffizi was a museum before the world even knew the word.

Anna Maria Luisa, the last Medici, sealed its fate in 1743. In her will, she declared the collections could never leave Florence. Because of her, what you see today is not fragments scattered across Europe, but Florence’s soul preserved intact.

So, when people ask why the Uffizi, the answer is this: nowhere else can you walk through thirty works and watch art evolve from rigid icons to living flesh. Let’s follow that arc, beginning with Botticelli, but not ending there.

His Primavera, painted for a Medici villa, is a garden of myth. Venus presides in calm, flowers bloom, winds chase nymphs. It is poetry in paint, a Renaissance hymn to beauty and rebirth.

Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi ties myth to history. He even includes himself among the worshippers, gazing at us directly. A bold act placing the artist inside the sacred story.

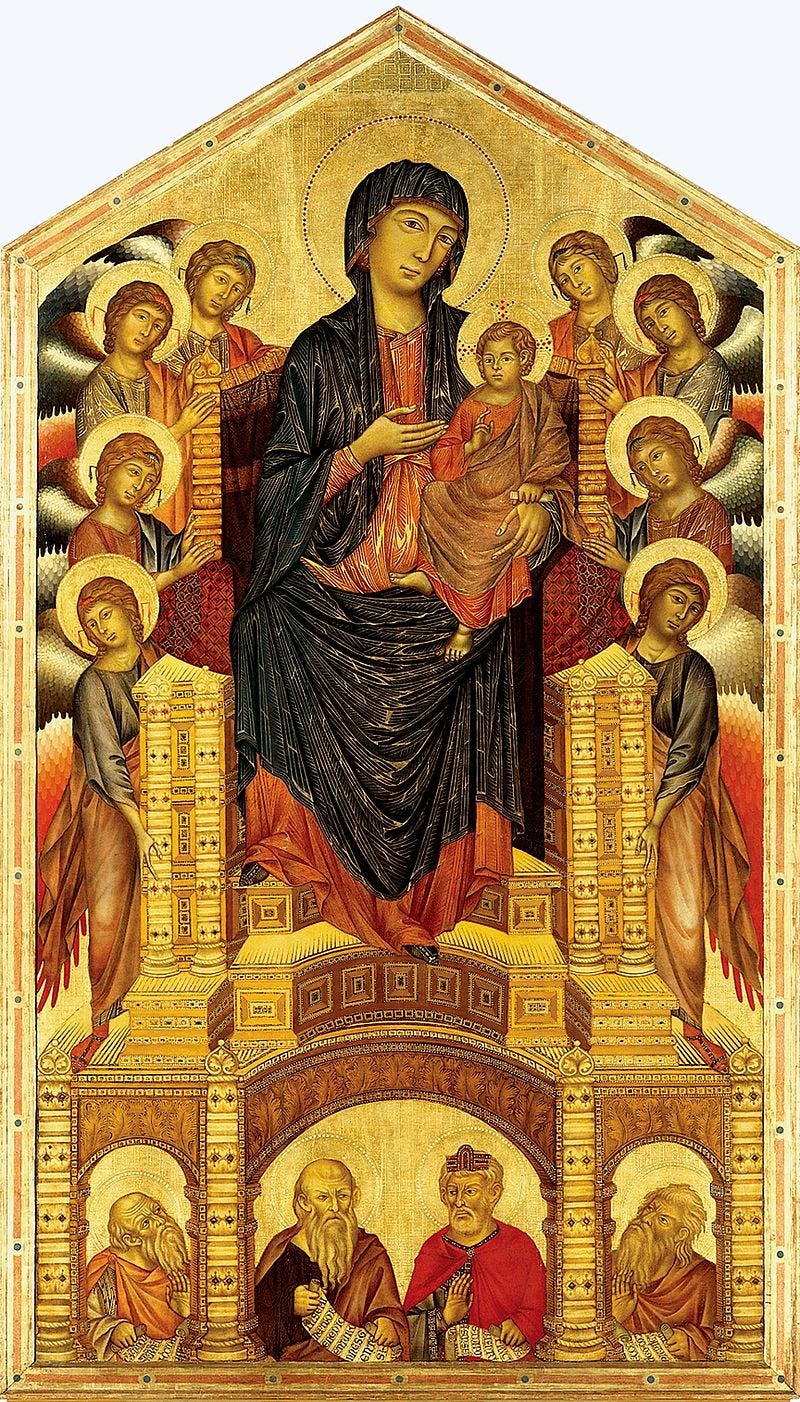

But Botticelli’s brilliance rests on foundations laid earlier. Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Maestà shows Mary enthroned in Byzantine solemnity. Huge, imposing, yet trembling with the first signs of human tenderness.

Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna, painted for a Florentine church, responds with grace. More decorative, more tender, Siena’s gift to Florence. A rivalry on wood panels.

Giotto changes the game with the Ognissanti Madonna. Mary is no longer flat but heavy with flesh. The throne has depth, the faces emotion. This is the first true step toward realism.

His Badia Polyptych carries the same shift. Saints lean forward with real weight, chiaroscuro shaping their bodies. Painting leaves behind symbols and starts to show life.

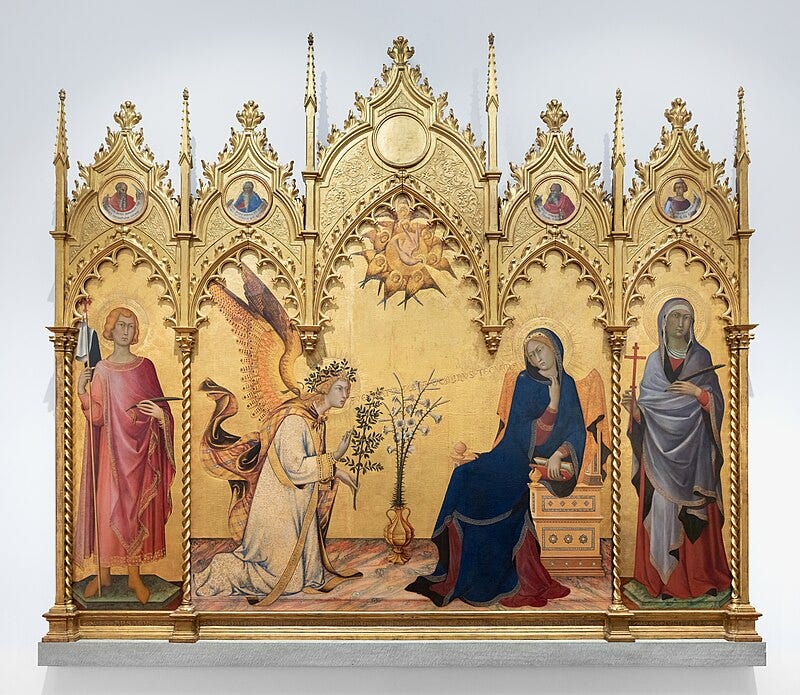

Simone Martini’s Annunciation refines Gothic elegance. The angel bows with theatrical flourish, Mary recoils in shock. It is stagecraft in gold leaf, sacred drama frozen in time.

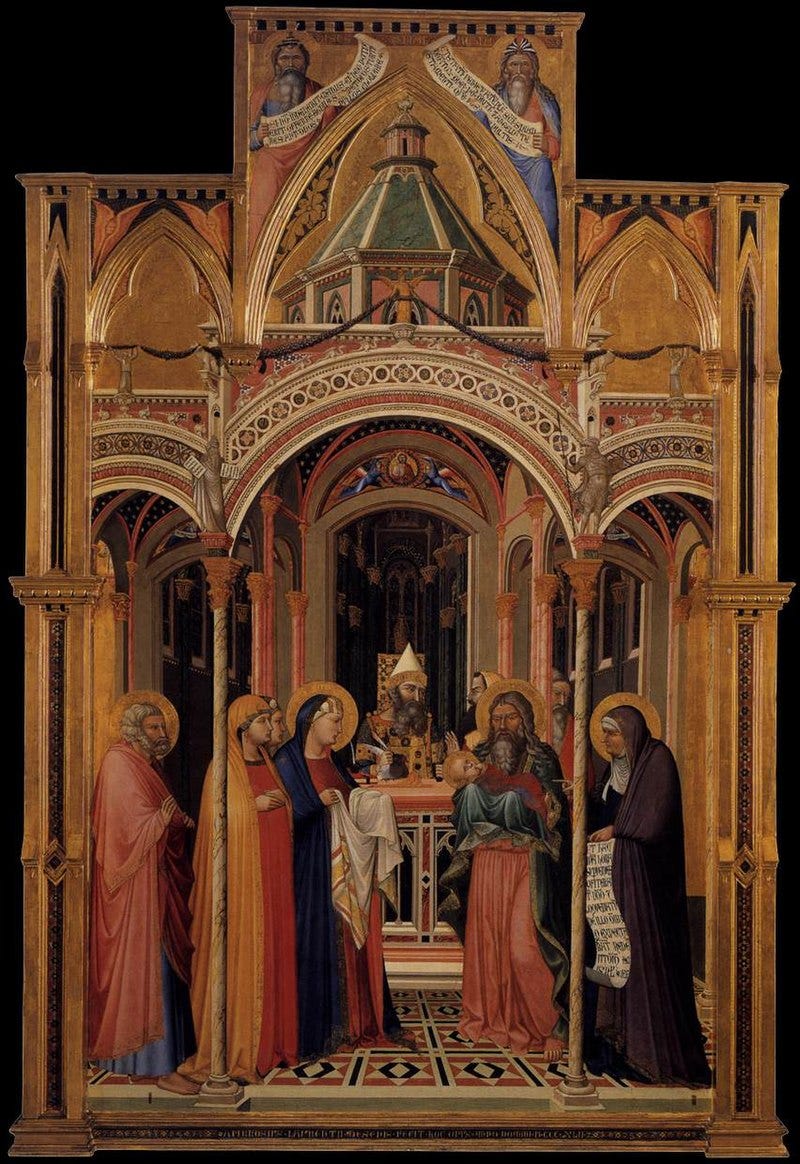

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Presentation at the Temple adds narrative force. Figures interact, architecture frames the story, gestures speak. Siena here anticipates what Florence would perfect.

By 1423, Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi dazzled Florence. Commissioned by banker Palla Strozzi, it glitters with gold and jewels. Horses, fabrics, flowers—every detail painted with loving precision. Gothic richness sliding into Renaissance observation.

But that’s only the beginning. The next 20 works take you further into battles painted like geometry, Leonardo’s restless genius, Michelangelo’s sculptural paint, Titian’s sensual color, Caravaggio’s shocking violence, and Artemisia’s defiance.