When the World Learned to Read

In a world where truth once lived and died in silence, the printing press gave it a voice and that voice tore empires, churches, and centuries of obedience apart.

Table of Contents

Main Section

Premium Section

How the Printing Press Set Fire to the Old Order

Under the glow of candlelight, a man once whispered to parchment. After Gutenberg, he roared across Europe.

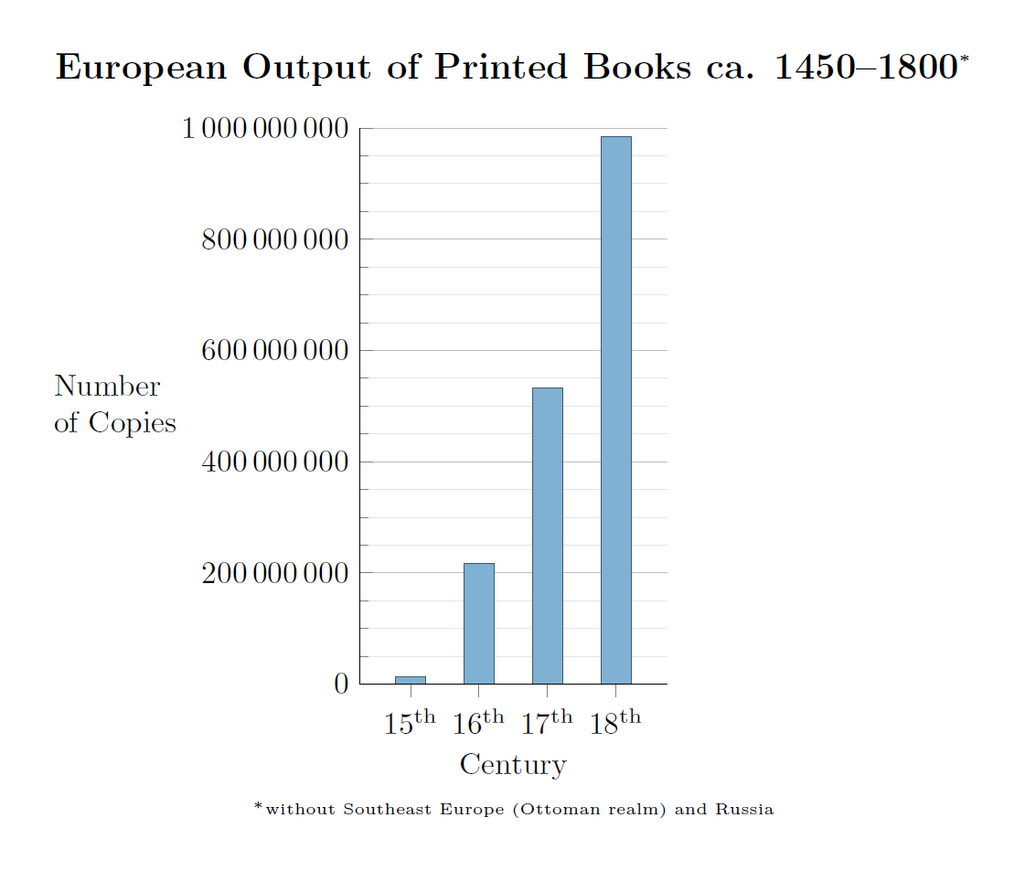

That’s the scale of disruption we’re talking about. Before 1450, the spread of knowledge was bound by time, distance, and the aching hand of scribes. After Gutenberg, it became a wildfire. But this story isn't just about a machine. It's about how a technical invention reshaped religion, cities, economies, and even the self. The printing press didn’t just revolutionize books, it rewired civilization.

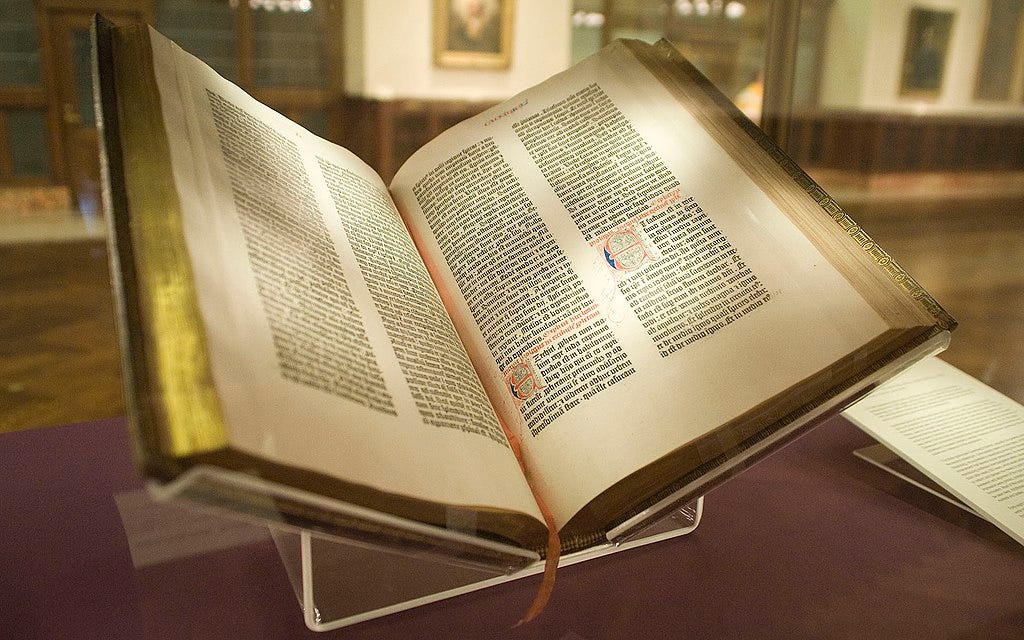

The first printing press was born in Mainz, Germany, around 1450. Johann Gutenberg, a goldsmith by trade, figured out how to combine movable type with ink and a press. Within fifty years, over 250 towns across Europe had presses. Venice, Paris, Rome, Kraków, Westminster—they lit up like stars on a new constellation. By 1500, 13 million books circulated in a Europe of 100 million people.

But why was it Europe, not China, that exploded from printing? The Chinese had woodblock printing centuries earlier. They even had movable type. But their language, with thousands of characters, made it unfeasible for widespread use. In Europe, with a limited alphabet and growing demand for books, the press arrived at just the right time and found dry timber everywhere.

At first, printers focused on religious texts. The Bible, once chained to monasteries, became accessible to the literate public. A silent revolution began in bedrooms and studies. People began to read alone. They interpreted texts on their own terms. That shift from listening to sermons to reading Scripture undermined the monopoly of the Catholic Church. It also sowed the seeds for Protestantism.

One effect was the rise of individualism. Before printing, identity was communal. Afterward, it became personal. The printed word nurtured solitude, reflection, and the idea of the self as interpreter, author, and thinker. The Gutenberg Era didn’t just birth readers, it created authors. People wrote because they could now be heard, printed, and preserved.

Another effect was urban growth. Cities that adopted printing grew 60% faster between 1500 and 1600 than those that didn’t. The connection wasn’t accidental. Printers sought out educated populations, universities, and centers of commerce. In turn, these cities attracted more people, more trade, more institutions. Knowledge wasn’t just power, it was population.

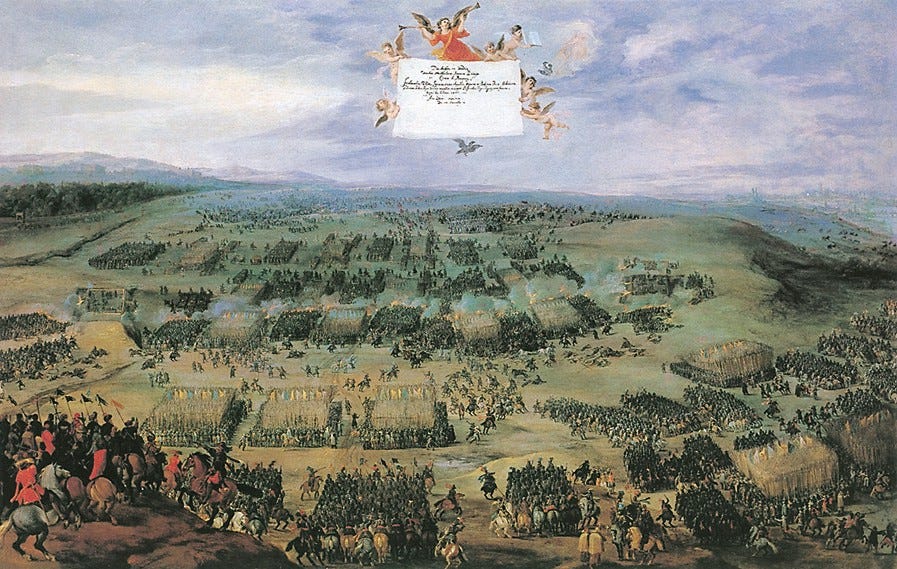

Yet this wasn’t all progress and harmony. Religious wars exploded in the decades after Gutenberg. People read Scripture and interpreted it differently. That freedom, born from reading alone, also fractured Europe’s spiritual unity. In some places, the printed word meant rebellion.

Even the rise of national languages came through printing. Before the press, Latin dominated intellectual life. Afterward, texts appeared in vernacular tongues: English, French, Italian, German. This didn’t just spread knowledge, it helped define nations. The book became a vessel for identity.

There’s another layer: the printing press helped dissolve old social structures. Guilds, communities, even village churches lost their grip as individuals turned to books and away from local customs. The act of choosing a book became an act of choosing a worldview.

And yet, printing didn’t cause utopia. Some cities adopted presses and still stagnated. Others boomed. The technology’s effects were uneven. Wars, geography, and politics all intervened. But where it stuck, printing amplified everything: conflict, literacy, creativity, ambition.

By 1500, books were 65% cheaper than they had been fifty years earlier. That price-drop alone created a market. Artisans, merchants, clerics… They now had access to technical manuals, mathematical treatises, medical guides. The world of the book burst its ecclesiastical cage and flooded into daily life.

The printed text made possible a new kind of citizen—someone informed, skeptical, and hard to govern blindly. By 1641, Samuel Hartlib wrote, “the art of Printing will so spread knowledge that the common people, knowing their own rights and liberties, will not be governed by way of oppression”.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant. The printing press didn’t just make people literate. It made them politically dangerous. Petitions, pamphlets, grievances—these became the weapons of the governed.

The French Revolution was fueled, in part, by this printed consciousness. So was the German Peasants’ War. When people understand their exploitation in ink, rebellion is no longer just a dream, it becomes a document.

But the impact wasn’t only political. The scientific world changed too. Printing allowed for replication, peer review, and the building of knowledge. Technical books on metallurgy, optics, and astronomy moved ideas out of monasteries and into workshops and cities.

This, as Dittmar argues, created spillovers. Ideas compounded. Education became an investment. And cities became hubs not only of goods but of knowledge. From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, printing was now a catalyst.

Yet even then, there were critics. English poet Andrew Marvell, in 1762, wrote: “Oh, printing! You have disturbed so much the peace of the world!”. He wasn’t wrong. Printing meant disruption. It shattered illusions, stirred wars, and toppled powers.

Still, the alternative was worse: silence.

From 1500 onward, books printed in national languages created standardized grammar, dictionaries, and a sense of cultural unity. Dante’s Divine Comedy in Italian predated the press, but once printing arrived, such vernacular literature reached the masses.

Translation exploded too. As books moved across borders, so did ideas. Cultures weren’t just preserved—they collided. And while conflict sometimes followed, so did synthesis.

The Renaissance, born in Italy, became European thanks to printing. Without it, we might not have had Erasmus in the north or Montaigne in France. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and Gutenberg’s press were part of the same wave, crashing over Europe from different shores.

By the 1600s, another shift began: from solitary reading to mass media. Pamphlets, newspapers, printed speeches… they shaped public opinion. Mass literacy changed politics. Once a government feared the sword. Now it feared the press.

And so did the Church. The Reformation wasn’t just a theological debate, it was a media revolution. Martin Luther was the first bestseller. His ideas, printed and spread, bypassed bishops and reached bakers.

Printing also changed how we value time. Before, information moved slowly. With books, calendars, maps, and clocks printed and distributed, people began to think of time in new, more linear ways. This shift underpinned the industrial mindset.

But there’s a twist. In the modern era, as books and newspapers became mass products, something was lost. The solitary, critical reader faded into the “print consumer.” The press that once liberated the mind began to shape it en masse.

And yet, the postmodern world owes everything to this machine. Social media, blogs, digital platforms—they are all descendants of Gutenberg’s wooden press. The logic is the same: amplify one voice to reach many.

The printing revolution was the moment humanity shifted from oral memory to textual permanence. From the village to the city. From the listener to the thinker.

Standard economic models miss this. The press didn’t just raise productivity in a narrow sector. It caused cities to grow, cultures to standardize, and people to imagine differently. History is not just about wars and treaties, it’s about how people think, speak, and write. The printing press changed what it meant to be human: to have a voice, a story, a legacy.

It taught Europe to argue with itself. It taught individuals to question. It taught citizens to organize.

And in doing so, it laid the foundation for modernity.

Not because of the machine.

But because of the minds it awakened.

Art - Monument to the Mighty 8th Air Force

Books Corner

The 10 Books That Set the Renaissance Ablaze

These weren’t just books, they were revolutions, words that tore through centuries of ignorance and lit the match for a world reborn.

The Renaissance wasn’t just an age of art and architecture, it was a revolution in how people read, thought, and understood the world. At the heart of it all were books. Ideas once confined to monasteries or elite courts now exploded across Europe thanks to the printing press. And certain works didn't just inform minds, they ignited them.

One of the most influential books of the Renaissance was The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. Though written in the early 14th century, it became central to Renaissance thought, especially in Florence. Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise wasn’t just theological, it was poetic, philosophical, and political. Humanists loved how he elevated the vernacular Italian language while blending classical knowledge with Christian allegory.

Next came Petrarch’s Canzoniere, a collection of poems that redefined love, memory, and beauty. Petrarch wasn’t just waxing poetic about Laura; he was laying the foundation for Renaissance humanism. His focus on the individual’s inner world, on emotional and spiritual self-reflection, became a blueprint for generations of writers and thinkers.