The Enduring Power of Roman Floors

They were built to be walked on, not remembered, yet centuries later, these forgotten floors speak louder than the empires that once stood above them.

Table of Contents

Main Section

Premium Section

Inside the Hidden Architecture of Roman Mosaics

They built them to last a lifetime, yet two thousand years later, we still walk their paths, unaware that beneath each step lies the buried genius of forgotten hands, the silence of civilizations lost, and the haunting beauty of art that never meant to outlive its makers.

You don’t just walk across a Roman mosaic. You step onto two thousand years of engineering, artistry, and cultural memory, fused into a surface that has outlasted the empires it once served.

Beneath your feet, the colored tesserae might gleam under sunlight, but what you’re seeing is only the surface. The real genius lies hidden, layer upon layer of carefully chosen stone, crushed pottery, lime, and pozzolana. What appears as art is also architecture. What looks decorative is deeply structural. These floors were built not just to be beautiful but to last through time, weather, footsteps, and even earthquakes.

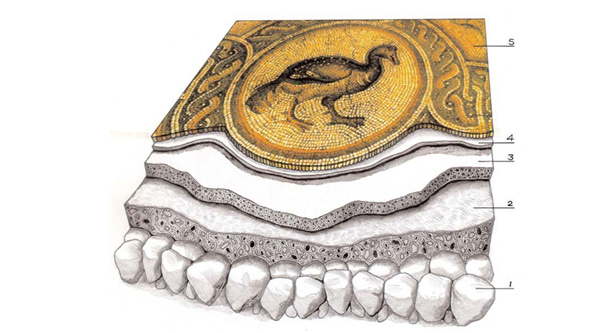

Vitruvius, the Roman architect of the 1st century BC, described the process in De Architectura. It begins with the statumen, a bed of large stones, laid directly on the compacted earth. This is followed by the rudus, a layer of stones and lime pounded into place to form a kind of ancient concrete. On top comes the nucleus, a fine mortar of crushed ceramics and lime, smoother and more compact. Then comes a thin bedding layer, rich in lime, where the tesserae, the small pieces of stone or glass, are pressed in before the mortar sets.

Pliny the Elder, a century later, offered variations and insights. He described charcoal layers used to keep out moisture, slopes added for drainage, and surfacing techniques involving polishing stones and lime washes. He even credited the Greeks for early terrace pavements but made it clear the Romans had elevated the technique. Mosaics became not just floors, but instruments of display, durability, and prestige.

And they weren’t all the same. The opus tessellatum used larger, regular tesserae, practical for corridors and porticos. The opus vermiculatum, made with tiny tesserae, allowed for intricate, almost painted scenes, often framed by borders of more geometric design. Then there was the opus sectile, where colored marble pieces were cut and fitted like a jigsaw—luxurious, high-status, and often reserved for the homes of the elite or the most sacred spaces.

In Tortoreto, the Villa Romana delle Muracche holds one such story. Excavated in the late 1980s, its structure reveals multiple phases of Roman occupation from the late Republic to late antiquity. The pavements in the pars urbana, facing the sea, were crafted with an eye toward refinement: a nucleus of lime and crushed brick, overlays of polished mosaic, and materials carefully selected from the surrounding Abruzzo geology. The layers reflect both function and adaptation, designed to hold against the shifting soils of a coastal landscape.

A very different example lies in Classe, near Ravenna. At the archaeological area of St. Severo, what begins as a Roman villa in the 1st century AD evolves into a Christian Basilica. The mosaics, layered with reused materials, speak of transformation. Pagan luxury gives way to Christian devotion, yet the techniques endure: tesserae pressed into lime, nuclei built from ceramic fragments, foundations adapted for new meanings without sacrificing durability.

Florence offers yet another dimension. In the “Cortile Romano” of its archaeological museum, fragments of mosaic pavements from ancient Florentia have been preserved. One came from under the Baptistery of San Giovanni—a Roman house later transformed into a bathhouse. The surviving floor sections, dated to the 2nd century, show careful layering even in an urban setting where space was tight. Here, the Romans used thinner mortars, perhaps due to architectural constraints, yet still maintained the stability and elegance expected in a cosmopolitan town.

In Dion, at the foot of Mount Olympus, mosaics were discovered beneath temples and houses that stood through multiple conquests and rebuilds. Their layers responded to local materials such as calcareous scree, volcanic soils, even charcoal. These pavements reveal how Romans adapted their system to regional geology while keeping to the core principles Vitruvius laid out. Dion’s mosaics, when cut and analyzed, show how even in a Greek city under Roman rule, the fusion of technique and terrain mattered.

And it wasn’t just the visible mosaics that mattered. The unseen parts, what we might call the floor’s architecture, were just as vital. The statumen had to resist groundwater. The rudus needed to distribute weight. The nucleus needed to be smooth enough to avoid cracking while drying. Modern studies, such as those conducted in sites like Italica, Petra, and Histonium, show how these components varied slightly but were always built with awareness of local materials and structural needs.

One conservator described discovering a mosaic in Vasto, Italy, where the bedding layer still held the fingerprints of the artisan who had once pressed the tesserae in place. That kind of intimacy, touch preserved in lime, is rare. But it happens. And when it does, it bridges centuries.

But not all stories are of resilience. In the 20th century, conservation often meant detachment. Mosaics were removed from their sites, mounted on cement backings, and displayed in museums. Their stratigraphy, the layers beneath, was lost. Builders’ methods erased in the name of preservation. The mosaics became images rather than structures.

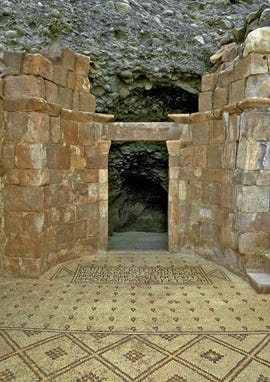

This mindset shifted in the late 20th century. Archaeologists and conservators realized that the context mattered. A floor isn’t just an artwork, it’s part of a room, a house, a building, a way of life. In situ conservation became the new standard. And with it came a rediscovery of techniques: lime mortars instead of cement, hand-mixed aggregates tailored to site, and restoration practices that respected the rhythm of ancient construction.

Modern conservationists have even revived some ancient tricks. Mortars are sometimes beaten as Alberti once described, with tools that compact the mixture and bring water to the surface. Linseed oil is used occasionally, just as the ancients did, to create a hard, water-resistant finish. In some projects, volunteers mimic the ancient rhythm of layering, not just to repair but to understand.

Geography shaped these choices too. In Jordan’s Agios Lot basilica, mosaics were built with desert durability in mind, rounded cobbles, charcoal layers, and debris from tesserae-cutting all recycled into the rudus. In Spain’s Italica, where summers are scorching, porous layers absorbed and released moisture strategically, helping floors stay intact through thermal shifts.

Today, these mosaics are often sheltered by modern structures: translucent pavilions, partial reconstructions of ancient buildings, or elevated walkways that allow visitors to see without stepping. Lighting is carefully managed to avoid heat damage. Interactive screens tell stories the floors cannot. But the best exhibitions are the ones that let the mosaic speak for itself, where the wear patterns hint at foot traffic, or the tesserae fade where sunlight once poured through a Roman window.

What’s powerful is not just the craftsmanship, but the emotion these floors can still carry. To see a lion mosaic in situ in a bathhouse at Dion, or to follow a black-and-white labyrinth in a Roman villa, is to witness a ghost of daily life. You can almost hear sandals scraping, water sloshing from buckets, the quiet murmur of conversation.

And if you pay attention, you can even sense the regional flair. North African mosaics, for example, feature more naturalistic animals and bright colors. Syrian examples tend to lean geometric, possibly influenced by earlier Hellenistic patterns. Each mosaic is both Roman and local—a cultural hybrid.

Some mosaics remain unfinished. In those, you find the clearest evidence of the process: tesserae scattered, mortar half-dried, outlines scratched into the nucleus. One such mosaic from Aphrodisias still bears the red pigment drawing of its intended design, never completed. It’s as if the artisan stepped away and never returned. These are haunting glimpses into a halted moment in time.

Even the patterns of wear tell stories. Smooth sections indicate heavy use. Corners, often intact, suggest protected zones. Some villas show deliberate repairs using mismatched tesserae, a quiet testament to resourcefulness.

Behind all of this were the artisans, often unnamed, sometimes slaves, sometimes specialists. They didn’t just place stones. They selected materials, mixed mortars, planned drainage, accounted for weight and movement. Their work survives where emperors’ statues have crumbled.

Some of these artisans worked for religion. Mosaics in early churches often repurposed pagan techniques for Christian narratives. The layers stayed the same, but the meaning changed from Bacchus to the Good Shepherd.

In Roman villas, mosaics were status symbols. A floor told visitors how rich, cultured, or powerful the owner was. Scenes from Homer, hunting images, portraits of philosophers—it was all messaging, encoded in marble and lime.

Yet Roman mosaics weren’t just for the capital or elite villas. Provincial cities in Spain, Britain, and North Africa all had their own mosaic schools. Local stones, local motifs, local style yet all within the Roman construction system.

Their survival is a testament to good engineering. Many endured floods, invasions, even deliberate destruction. Some cracked but held together. Others were buried in mud and survived perfectly sealed.

Not all stories are lucky. War, looting, and neglect have erased many mosaics. But the ones that remain now benefit from 3D scanning, chemical analysis, and global cooperation.

Modern conservators are trained in both chemistry and history. They know how to interpret a lime mix, but also how to tell a story. Their job is part science, part resurrection.

Because these mosaics are more than art. They’re cultural memory encoded into architecture. They tell us how the Romans lived, what they valued, and how they built for forever.

And perhaps that’s the most remarkable part. In a world of mass-produced flooring, Roman mosaics stand as a challenge. They weren’t cheap. They weren’t fast. But they endure.

By the 5th century, mosaic-making slowed, replaced by simpler construction. But the skill lingered. In the Renaissance, Alberti and others studied these floors, trying to learn from them. Even today, artists recreate the look—but rarely the layers.

Yet in every well-preserved mosaic—whether in Tunisia, Turkey, or Italy—you feel something ancient still pulsing. A design made by hands long gone, on a floor meant to outlive them.

Because you don’t just visit a Roman mosaic. You enter time. And for a brief moment, time holds still.

Art: Roman floor mosaic from the Baths of Ocriculum by Giussippe and Franciso Panini

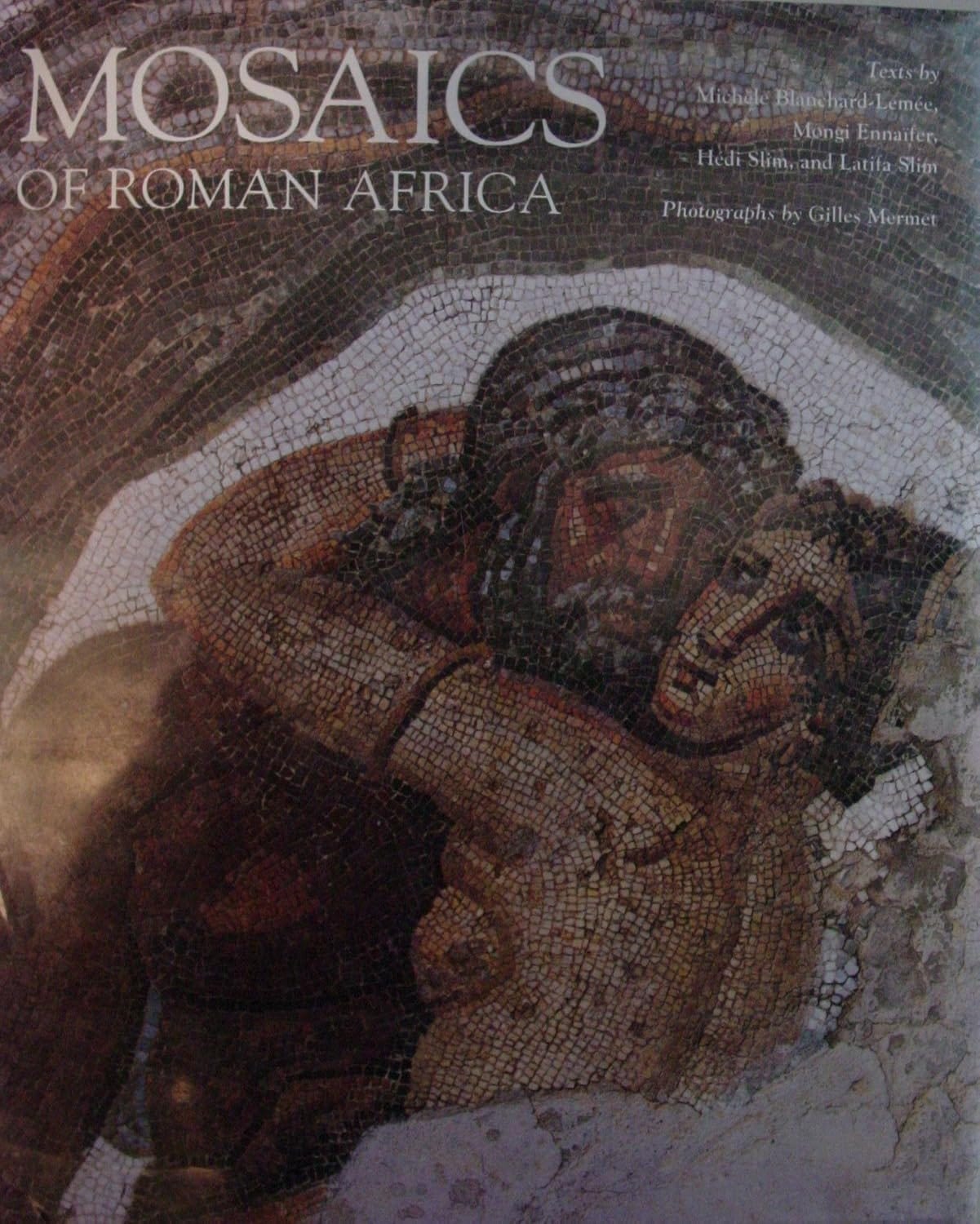

Book Corner

Between the 2nd and 6th centuries AD, Roman North Africa, especially present-day Tunisia, produced some of the most spectacular floor mosaics in history, commissioned by wealthy provincials to showcase their status and taste. Filled with gods, daily life, and nature, these mosaics are now our most vivid window into the art and luxury of a world where few paintings have survived.

Advertisement

10 Places You Must See if Roman Mosaics Still Make You Feel Something

Scattered across the ruins of an empire, these mosaics weren’t meant to survive yet they remain, fragile and defiant, holding the last breath of a world that refused to vanish quietly.

Roman mosaics weren’t made to be admired from a distance.

They were meant to be walked on, lived with, worn down by time—and yet they survived.

If you're chasing the kind of beauty that outlived empires, here are ten places where Roman mosaics still breathe.

Villa Romana del Casale – Sicily, Italy

Deep in the hills of Piazza Armerina lies a Roman villa so lavish, its floors cover over 4,000 square meters. The mosaics aren’t just beautiful—they’re cinematic. Hunters chase wild beasts across continents. Women in bikinis lift dumbbells. The scenes are sharp, emotional, and alive. This isn’t just a villa; it’s a glimpse into a world that refused to stay buried.