How to Read a Book

Adler’s Forgotten Art of Reading

The first time I tried to read War and Peace, I felt stupid. I’d read a page, turn it, and realize nothing had stuck. The names blurred together. The conversations felt like they were happening in a room I wasn’t invited into.

At first, I thought the problem was Tolstoy. Then I thought the problem was me. But after a few days, the truth became clear in the way it always does with hard books. I stopped reading. I just quietly moved on; the same way people abandon gym memberships.

What bothered me later wasn’t quitting. It was the reason. I wasn’t lazy, and I didn’t hate reading. I was just reading the wrong way. I was treating Tolstoy like a news article, moving sentence by sentence, waiting for the meaning to show up on its own. That’s when it hit me: most people don’t really know how to read serious books. They know how to get through pages. But they don’t know how to wrestle with ideas.

That’s exactly what Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren tried to fix in How to Read a Book. Their point is simple. Reading isn’t passive. It’s an art form. And if you don’t develop it, you can live in a society full of books and still end up with a population that can’t think. In this article, I’ll break down Adler’s four levels of reading, and the shift that changes everything: learning to read a book’s structure before you drown in its details.

The most important thing Adler does is draw a line between two kinds of reading. Reading for information and reading for understanding. Information is what modern society specializes in. It’s what you get when you skim headlines, watch documentaries, scroll summaries, and absorb facts. But understanding is different. Understanding means the ideas become yours. It means you can explain them without repeating the author’s words. It means you can test them. It means you can disagree intelligently. It means you can see the skeleton beneath the surface.

And books like War and Peace aren’t written to give you information. Tolstoy isn’t trying to deliver a set of facts about Russia. He’s trying to show you human nature under pressure. He’s showing what war does to a society, what love does to a person, what pride does to a family, what history does to a generation. That kind of book cannot be skimmed. It has to be lived through.

This is where most modern readers collapse. They expect reading to feel smooth. They want a book to behave like a Netflix series. And when it doesn’t, they assume the book is boring or irrelevant.

Adler even uses a metaphor that is almost embarrassingly simple, but it captures the entire truth. Reading is like catching a ball. The writer throws. The reader catches. But if the reader stands there half-asleep, the ball hits the ground. The writer may have done everything right. The throw may have been perfect. But the message never lands because the reader never participated. That is what passive reading is. It’s watching the ball roll away and then blaming the pitcher.

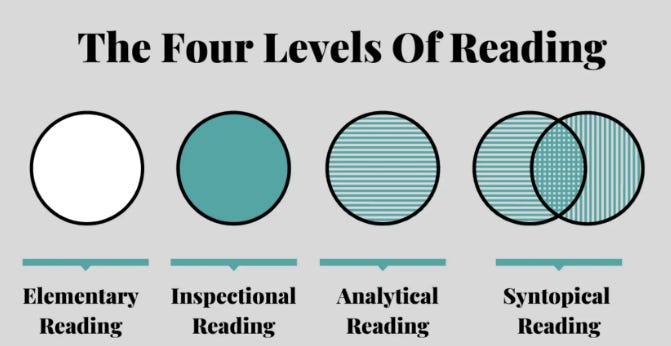

So, when you finally sit down with a serious book, your mind panics. It feels heavy. It feels slow. It feels like a burden. Not because the book is flawed, but because your brain has been trained for a different world. This is why Adler’s four levels of reading are so useful. They don’t just explain what good readers do. They explain why most people fail without even knowing what went wrong.

The first level is elementary reading, which is basic literacy. Most people assume that once they can read words, they can read books. But literacy is not intelligence. Literacy is the ability to decode symbols. That’s like knowing how to hold a sword. It doesn’t mean you know how to fight.

The second level is inspectional reading, and this is where most people make their first real mistake. Inspectional reading means you don’t open a book and blindly start at page one like a machine. You inspect it. You look at the table of contents. You read the introduction. You scan the chapter headings. You flip through pages. You ask what kind of book this is and what it’s trying to do. Most people don’t do this because they think it’s cheating. But Adler argues it’s the opposite. It’s intelligent. It’s strategic. It’s the act of preparing your mind so you don’t get lost.

When I failed with War and Peace, this was part of the reason. I treated it like a normal novel. But it isn’t a normal novel. It’s a philosophical argument about world and society disguised as storytelling. You have to approach it differently by orienting yourself first, the way you would before entering a foreign country.

The third level is analytical reading. This is where reading becomes serious. Analytical reading means you aren’t just following the author’s words. You’re trying to understand his structure. You’re asking what he is arguing, what he is assuming, and what he is trying to prove. You begin to track the book like a living thing. You notice patterns. You identify key terms. You see what matters and slowly, the book stops being a collection of pages and becomes a coherent mind speaking to you.

This is also where reading stops being comfortable. Because analytical reading forces you to think, slow down, and admit when you don’t understand. It forces you to reread, to pause, to take notes, to argue back in your head. This is the part most people avoid. Not because they can’t do it, but because they don’t like the feeling of resistance. They want reading to be easy. But real reading was never meant to be easy.

The fourth level Adler describes is syntopical reading, and this is the level that turns reading into power. Syntopical reading means you don’t read one book in isolation. You read multiple books on the same topic and compare them. You force authors to speak to each other. You look for contradictions. You look for agreement. You build your own understanding from the clash. This is how serious thinkers are formed. Not by finding one author and worshipping him, but by reading widely enough to see the larger conversation.

Once you reach that level, you stop being a consumer of ideas. You become a judge of ideas. And that is a rare skill now. In fact, it may be one of the rarest skills in modern society.

This is where the cultural consequences start to become obvious. Because a society doesn’t fall apart only when it loses wealth or military strength. It falls apart when it loses judgment. When people cannot follow arguments, they become vulnerable to slogans. When they cannot read deeply, they cannot think deeply. When they cannot think deeply, they become emotionally ruled. And when people become emotionally ruled, they become easy to control.

That is why this book matters. Adler wasn’t writing a self-improvement guide. He was writing a defense manual for the mind. He was trying to train readers to resist manipulation, intellectual laziness, and the shallow world that modern media naturally produces.

The funny thing is, if you apply Adler’s approach, you don’t just become better at reading books, you become better at reading people. You start hearing what’s missing in arguments and begin to notice when someone speaks confidently but says nothing. You stop being impressed by fancy phrasing. You begin to ask sharper questions. And slowly, your mind becomes harder to deceive.

That’s the real payoff.

And it’s also why so many people struggle with books like War and Peace. They expect Tolstoy to carry them. But Tolstoy doesn’t carry anyone. He throws the ball. You have to catch it. You have to participate. And if you do, something strange happens. The book stops being a burden and starts becoming a world you can walk inside. The names stop being confusing. The characters stop being distant. The conversations start to feel alive.

I think that is the simplest way to describe great books. They are difficult because they contain more life than we are used to processing. They demand more attention than our culture trains us to give.

And that leaves us with an uncomfortable question.

If deep reading is one of the skills that creates clear thinking… what happens to a civilization when most people can no longer do it?

Wow. This is enlightening. Thank you! I now have a new approach to my favorite pastime of reading.

A timely article for me. I recently read Junger's On Pain. I felt underwhelmed despite some hyping it. I skipped the supplied introduction and the translator's own separate introduction. I then read these which added historical info I was unaware of (it was written in the 1930's as Hitler had just come to power in Germany). This prompted me to seek out other views on it. I am now reading the essay for a second time with a different perspective.

So this is just to say it works with non-fiction too. If you have read some important piece and walked away baffled as to why anyone cares, perhaps getting different perspectives may help understanding and prompt a rethink.

I am currently doing this with TS Eliott's The Waste Land too.