Samurai, Scholars, and Silence: What Japan Can Teach the Modern World

The samurai didn’t vanish. They were absorbed, rewritten, and used to forge a modern nation. What we remember is a myth. What was lost is far more human.

Table of Contents

Main Section

Premium Section

Samurai, Scholars, and Silence: What Japan Can Teach the Modern World

What if the most dangerous men in history weren’t the ones who raised swords but the ones who knew when not to?

For centuries, Japan was ruled not by chatter or chaos, but by a class trained in stillness, obedience, and discipline. The samurai began as warriors, yes—but in peacetime, they became teachers, writers, and moral examples. What’s remarkable is not just how they changed, but how Japan changed with them. And what survives of that legacy today might offer something modern societies desperately lack: a moral code not built on noise or outrage, but on character.

In the West, we often link freedom to rebellion. Journalism is adversarial. Schools are battlegrounds of opinion. Public discourse is flooded with claims of personal rights. But in Japan, legitimacy has long rested on something quieter, something older. In journalism, in education, and even in national memory, echoes of bushidō still shape behavior. Not because it was perfect. Not because it was historically precise. But because people believed in it and belief, when internalized deeply, becomes behavior.

Andrew Horvat1, a journalist and educator who lived in Japan for decades, argues that samurai values survive not because they were ever codified perfectly, but because they were absorbed by key institutions. Early Japanese reporters came from samurai backgrounds. Their job wasn’t to provoke but to inform, to interpret government policy for the people during rapid modernization. Newspapers weren’t claiming “rights” to speak truth to power. They earned moral credibility by being morally credible. Lose that, and they lost their readers.

This is not abstract. In 1972, one Mainichi reporter was caught in an affair with a government source. The scandal cost the paper 400,000 subscriptions in a matter of months. The man’s reporting had exposed government lies but his personal behavior violated public expectations of moral uprightness. In Japan, it wasn’t enough to be right. You had to be honorable. Journalists were expected to be modern-day samurai not in armor, but in ethics.

Even today, major newspapers in Japan don’t run humor columns or letters that contradict their own editorials. They don’t treat themselves as marketplaces of ideas. They treat themselves as moral institutions. Their reporters are expected to be educated, restrained, and guided by character, what the Japanese call jinkaku. That word keeps coming back. It doesn’t just mean personality. It means moral presence.

That same expectation shows up in Japan’s universities. Many of the country’s leading private schools were founded by ex-samurai, men who believed that education wasn’t just about facts, but about forming character.

Gakumon wo tsūjite ningen keisei or “character building through learning.” That’s the motto of Dokkyo University. Others have similar ones. At many schools, students still rise, bow, and sit on command during ceremonies. It may seem stiff to outsiders, but it reflects a vision of education as moral preparation—not just academic advancement.

Professors aren’t just teachers. They’re mentors. Sensei. They’re expected to guide students long after graduation, helping place them into jobs and shape their life choices. And just like in journalism, professors who fall short in their private lives lose public respect. Even minor infractions, like a traffic violation, can lead to forced resignations. In this system, integrity isn’t just personal. It’s institutional.

This moral expectation traces back to how the Tokugawa shogunate reshaped the samurai. After centuries of war, they needed warriors to become civil administrators. Confucian scholars like Yamaga Sokō and Ogyū Sorai infused the samurai with ethics—benevolence, restraint, loyalty to public order. Samurai were now to rule not with force, but with example. They would earn trust through character, not coercion.

And here’s the part that stings modern sensibilities: it worked. Japan maintained internal peace for over 250 years under this model. And when the Meiji Restoration came, many of these same former samurai became the architects of modern Japan founding newspapers, universities, ministries. They carried their sense of duty into these institutions. And through them, that legacy still breathes.

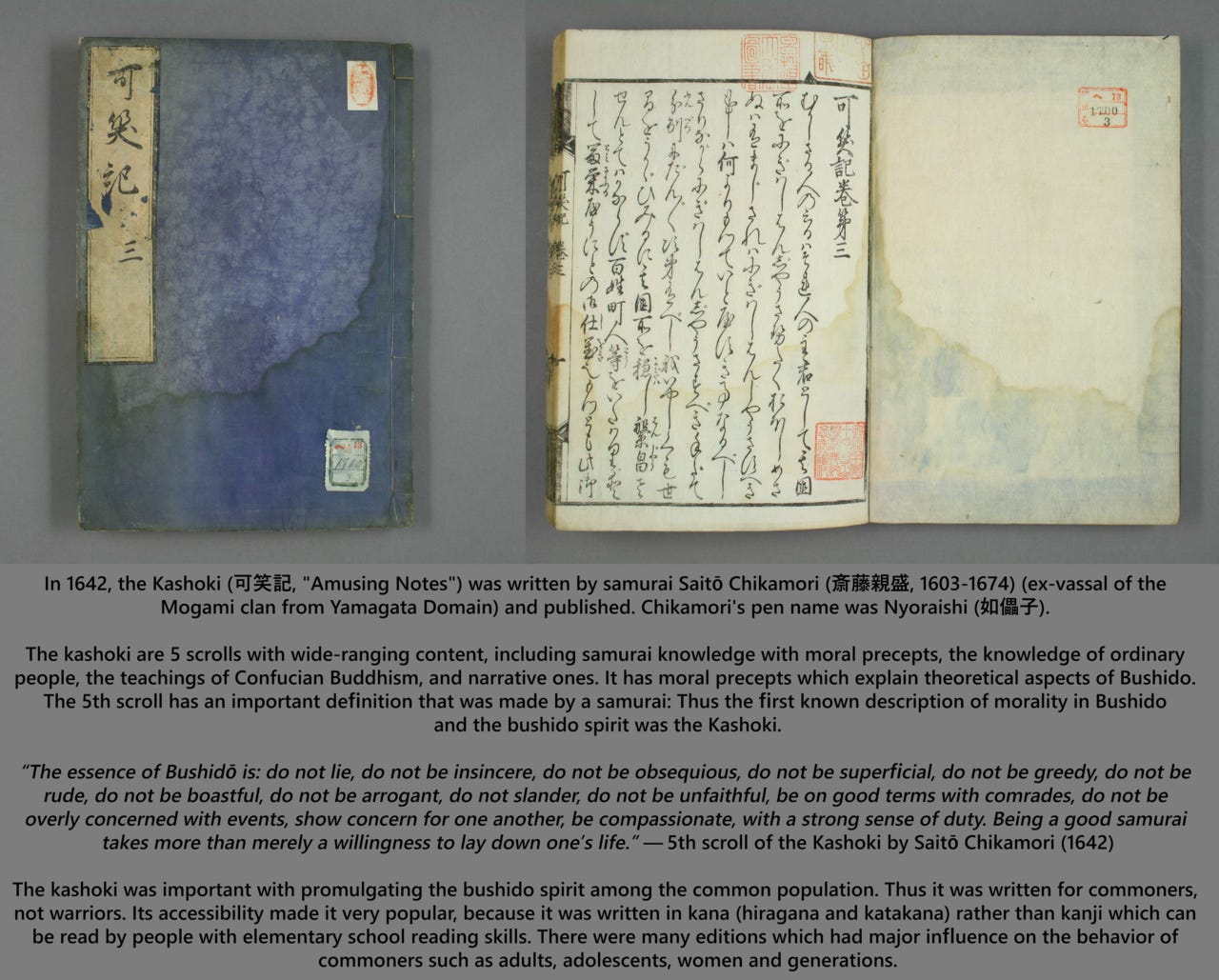

But don’t confuse legacy with literal history. Much of what we think of as bushidō was invented or redefined in the Meiji era. Nitobe Inazō’s famous book Bushido: The Soul of Japan was published in 1900 in English. It was more of a cultural ambassador’s attempt to explain Japanese ethics to the West than a manual of real samurai life. Nitobe referenced more Christian and European thinkers than Japanese ones. He admitted bushidō wasn’t a written code but a set of maxims handed down orally.

Critics today call it invented tradition and they’re not wrong. But they miss the point. People lived by it. Students were raised on it. Institutions absorbed it. Myths, when sincerely believed, create their own truths. Kurosawa’s noble rōnin, the loyalty of the 47 retainers in Chūshingura, and the quiet dignity of bushidō heroes—they all reinforced what people thought samurai should be, even if they never were.

And that’s the key: Japan didn’t obsess over whether bushidō was historically accurate. It mattered more that it modeled values worth preserving. In a world obsessed with factual correctness but starved of moral coherence, that might be the more important lesson.

Ethan Segal2, in his article on using samurai to teach critical thinking, makes a brilliant pedagogical move. He encourages students to compare Hollywood’s image of samurai with real primary sources such as woodblock prints, historical records, even theatrical scripts. In doing so, he doesn’t dismiss the myth. He uses it as a starting point for inquiry. That’s the kind of thinking bushidō, rightly taught, could inspire not blind obedience, but disciplined questioning.

Segal’s students examine why films like The Last Samurai dress heroes in traditional garb while the real Saigō Takamori wore a Western military uniform. They discuss why loyalty was exaggerated as a samurai virtue during the Tokugawa period precisely when actual warfare had ended. They begin to see history as layered, nuanced, and moral not just a timeline of battles and names.

In that sense, bushidō becomes a tool for intellectual formation. It invites students to explore how societies invent values, mythologize behavior, and pass down cultural codes. The same way Americans internalize the Founding Fathers, or Brits the Blitz spirit, Japanese students navigate samurai myths to explore who they are and what kind of citizens they want to become.

This is critical thinking rooted in cultural literacy, not ideology. And it’s rare. Because most modern education systems, especially in the West, now focus almost entirely on skills, metrics, and job readiness. The soul, the character, is an afterthought.

But Japan, even as it modernized, never fully abandoned the idea that institutions are morally formative. That professors shape lives. That newspapers guide the nation. That values must be taught as well as debated. This isn’t to idealize Japan, it has its contradictions, its pressures, its deep flaws. But there is something quietly admirable in a society that still believes restraint, humility, and character matter.

The irony is, many of these values are now fading in Japan too. The global push toward individualism, economic pressure, and digital noise is taking its toll. Yet even now, remnants of that moral framework remain. The silence in a ceremony. The bow before entering a classroom. The expectations placed on a teacher. The fury when a journalist violates public trust.

In a world where every disagreement becomes content, and every scandal becomes a joke, Japan’s old ways might seem stiff. But they’re not empty. They’re rooted in something long-term. Something that asks more of people than self-expression. It asks them to grow up.

That might be what modern societies need most. Not more data. Not more debate. But more expectation. Not just of what we can say but how we choose to live.

The samurai learned to master themselves because they had to. It was the only way to transform from killers into keepers of peace. And they did it not by abandoning pride, but by channeling it into discipline.

Today, our pride is mostly noisy. We announce ourselves constantly. But the samurai model, flawed as it may be, invites us to ask: what if the highest form of strength isn’t expression but control?

That’s the legacy Japan still carries in its classrooms, newsrooms, and rituals. That’s what bushidō offers, not nostalgia for swords, but a challenge to grow into something higher. Something worthy of trust. Something quiet and strong.

Japanese Art

The Last Samurai Wasn’t the Last: How Hollywood Hijacked Japan’s History

What if the story you love is the history that never happened?

The Last Samurai gave the world a romantic vision: a fallen American soldier finds redemption among noble warriors in a fading world. The village is serene. The swords gleam with honor. The rebellion is pure. It's gripping, cinematic, and emotionally rich. But it's also wrong, at least in parts that matter.

… continued in premium section …