The Classical Secret Behind Bernini’s Baroque Genius

Bernini weaponized antiquity, turning classical beauty into a force that could move, shock, and captivate like never before.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini is often hailed as the genius of the Baroque, the man who turned marble into flesh and motion. His sculptures explode with energy. His architecture pulls you into an emotional current. His saints swoon, his gods chase, his fountains erupt. But beneath all this theatrical flair lies a truth few people recognize: Bernini built his radical Baroque style on classical foundations.

The standard story paints Baroque as a rebellion against classical restraint. If the Greeks and Romans sought balance, proportion, and order, the Baroque aimed for shock, awe, and divine drama. But Bernini never saw those worlds as opposites. He fused them. He used classical forms to create new emotional realities, drawing power from antiquity while crafting something the ancients never dared attempt.

Take his “Apollo and Daphne.” At first glance, it’s a masterpiece of movement—Daphne mid-transformation, leaves sprouting from her limbs as she escapes Apollo. But look closely at Apollo’s stance. It’s a direct nod to the “Apollo Belvedere,” a Roman copy of a Greek original. Bernini doesn’t just reference it. He reanimates it. The serene, idealized god becomes a desperate figure caught in the final moment of pursuit. Ancient stillness becomes Baroque urgency.

In his “David,” Bernini makes another bold move. While Michelangelo’s David stands contemplative and composed, Bernini’s version coils with tension, his muscles pulled tight as he winds up to strike. His twisted torso recalls the Borghese Gladiator and the Menelaus supporting Patroclus. Bernini knew these ancient works well. He used their physical language to deliver a psychological punch.

Bernini didn’t mine antiquity for style points. He believed classical art revealed deeper truths. He told students to copy ancient works before copying nature. To him, the Greeks had already perfected the essence of the human form. That perfection offered more than beauty—it gave him the tools to express the divine.

His architecture followed the same logic. The sweeping colonnade of St. Peter’s Square may look like a Baroque embrace, but Rudolf Wittkower—an authority on Renaissance and Baroque architecture—called it one of the most Greek-inspired structures built after antiquity. Its solemn rhythm and symmetrical order reflect ancient ideals, reframed for a Catholic empire.

Nowhere does this synthesis become more deliberate than in Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, the oval church Bernini designed for the Jesuit novitiate. Its plan reflects the ancient Temple of Virtue and Honor, where worshippers had to pass through one sanctuary to reach another. Bernini applied that moral geometry to Christian theology. His church guides the visitor from darkness to light, from earth to heaven, from human weakness to saintly transformation.

Bernini’s artistic world wasn’t limited to sculpture and stone. He immersed himself in the theater. He wrote plays. He designed stage sets. He created illusions that fooled and overwhelmed audiences. He staged sunrises so convincing they brought gasps, and mock floods that sent crowds fleeing—until the illusion melted into laughter or awe. These weren’t just tricks. They were moments of catharsis. They turned viewers into participants.

This obsession with emotional transformation echoed a larger trend in Rome. Jesuits and Oratorians experimented with new theatrical forms that blended ancient Greek drama with Christian themes. They rediscovered Aristotle’s Poetics and its concept of catharsis—the purging of emotion through tragedy. Artists and composers began building works that aimed to stir the soul, not just educate the mind.

One production stands out: Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s “Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo,” performed in 1600. It wasn’t just a play. It was a religious opera in which allegorical figures—Body, Soul, Time—argued about salvation. It ended with the voices of the Blessed and the Damned. The goal wasn’t entertainment. It was repentance.

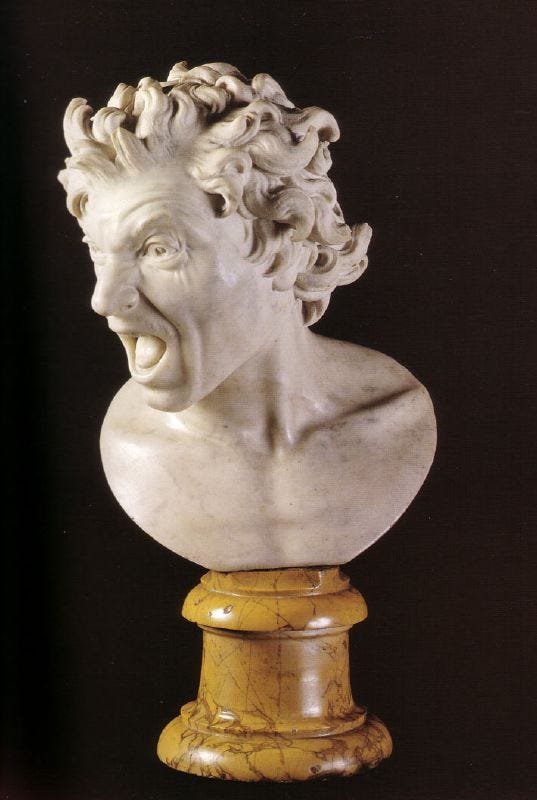

Bernini absorbed that spirit. Around 1619, he sculpted two busts: The Blessed Soul and The Damned Soul. There’s no narrative scene. Just two faces—one in agony, one in bliss. They resemble ancient masks of Tragedy and Comedy. But these aren’t stage props. They’re portraits of eternity. They show salvation and damnation not as abstract ideas, but as human experiences.

This use of classical forms to stir Christian emotion runs through Bernini’s career. He didn’t just use Greek models. He revived their purpose. Ancient tragedy aimed to move, to elevate, to leave you changed. Bernini pursued the same goal, but with a new language—Catholicism, saints, angels, martyrdom.

When Bernini visited France in 1665, he mocked most of what he saw. But he praised Nicolas Poussin, the restrained French classicist. That’s telling. Bernini, the great Baroque sculptor, saw in Poussin’s quiet scenes the same dramatic focus he pursued. They worked in opposite styles, but they shared the same mission: to use art to shape the soul.

Bernini succeeded because he didn’t see antiquity as a dead past. He saw it as a living force. He used its discipline, its beauty, and its myths to build something new. He took Greek serenity and infused it with Catholic fire.

We remember him today for the swooning saints, the spiraling columns, the ecstatic angels. But if we stop there, we miss the deeper story. Bernini wasn’t just the artist of the Baroque. He was its philosopher. Its dramatist. Its bridge to the ancient world.

And in that fusion—of pagan form and Christian emotion, of old wisdom and new power—he created something timeless.

Art

Featured Book

Looking for a Ghostwriter …

If you have great ideas but no time to write them…

If your brand sounds generic, even though your story isn’t…

If you’ve tried content but it never lands…

I offer ghostwriting services that turn your thoughts into sharp, engaging posts, threads, or articles—built to grow your audience and reputation.

Whether you're a founder, creator, or expert, I help you sound as good on paper as you do in person.

Let’s make your message unforgettable.

→ Contact me to get started.

Beautiful and outstanding work You do!! Thank you!🙏