The Lost Tribes Weren’t Lost — They Became Us

They were dragged into exile, erased from history, and called lost. But what if the blood of the Ten Tribes never vanished, only changed its name.

The Lost Tribes Weren’t Lost — They Became Us

What if the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel didn’t vanish after all? What if they crossed empires, shaped ancient superpowers, and quietly became the foundation of some of today’s most powerful nations? That’s the provocative claim made by historian Steven M. Collins.1 And whether or not you agree, the evidence he compiles from classical historians, archaeological findings, linguistic clues, and biblical records demands attention.

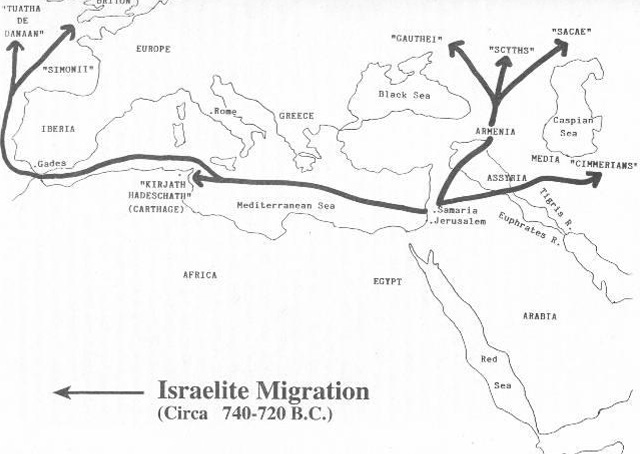

The traditional story ends in 721 BC, when the Assyrian Empire destroyed the northern Kingdom of Israel and forcibly deported its population. These tribes, ten of the twelve that made up ancient Israel, were relocated to regions around the River Gozan and the cities of the Medes, roughly in today’s Iran and western Afghanistan. The Bible records this exile in 2 Kings 17. After that, most scholars shrug and call them “lost.”

But Collins argues that the tribes didn’t disappear. In fact, he claims they multiplied. The Bible itself seems to support this. In Hosea, God promises to make the Israelites as numerous as “the sand of the sea.” In Genesis 49, Jacob gives detailed prophecies about what will happen to each tribe “in the latter days.” Nowhere does the Bible suggest extinction. It says transformation.

Josephus, the 1st-century Jewish historian, wrote that the ten tribes were still alive in his time and living beyond the Euphrates. He called them an “immense multitude,” too vast to count. In other words, nearly 800 years after their exile, they were not only alive — they were thriving in a region the West had largely stopped watching.

Here’s where the Parthian Empire comes in. From roughly 250 BC to 227 AD, Parthia controlled a massive territory that stretched from the Euphrates River deep into Central Asia. It was the only power in the East that consistently resisted Rome. Yet most people today have never even heard of it. Collins suggests this is no accident. According to him, Parthia’s population, tribal, decentralized, and governed partly by priestly authority, preserved key characteristics of ancient Israel.

The similarities are striking. Parthia was not ruled like Rome. It had a council of elders, tribal governance, and a hereditary priesthood. These political structures mirrored the decentralized, tribal organization of Israel under the judges and early kings. Some Parthian cities even bore names that matched those of Israelite tribes, including Issachar, Naphtali, and Zebulon.

Linguistic links also raise eyebrows. Collins cites historians who noted that terms like Sacae or Scythian, names used by Greeks and Romans to describe nomadic peoples near Parthia, may derive from Isaac, the patriarch of Israel. The Scythians, like the Parthians, were mounted warriors with longbows and composite armor. Herodotus described them as fierce, independent, and entirely foreign to both Greek and Persian systems.

When the Parthian Empire fell to the rising Sassanid Persians in 227 AD, many of its people began to migrate westward. This mass movement is well-documented. Waves of nomadic and tribal groups — including the Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Vandals, and others — poured into Europe from the East. Collins argues that these were not random migrations. He believes they were the next chapter in the story of the Ten Tribes.

There’s historical precedent for this idea. Roman authors noted that some invading tribes claimed descent from noble patriarchs. Early Anglo-Saxon genealogies include names suspiciously similar to biblical ones: Dan, Ashur, Naphtali. The Saxons themselves may have believed they were “Isaac’s sons” — hence, “Saxons.” It sounds far-fetched, but the repetition of names, customs, and legends across centuries and regions begins to add up.

In India and Central Asia, tribal legends speak of forefathers who came from the West and followed divine laws. The Pashtuns of Afghanistan and Pakistan have long claimed descent from King Saul. Yes, the same people often referred to as the Taliban. Even in remote parts of East Asia, Japanese Shinto rituals include purification practices and food taboos that echo Mosaic law and some claim they were introduced by travelers from the West.

Archaeological evidence offers further support. Burial sites attributed to Scythians have yielded Hebrew inscriptions. Some contain artifacts with menorah motifs and script similar to ancient Hebrew. In the Caucasus, isolated mountain communities practiced circumcision and sabbath observance well into the Christian era, despite being cut off from Jewish influence.

Of course, Collins doesn’t claim every European or Asian tribe descends from Israel. His point is more targeted: that large segments of the population — particularly among the Scythians, Parthians, and later Germanic tribes — may have carried forward the cultural and genetic legacy of the Ten Tribes without knowing it.

Critics say it’s speculative, and it is. DNA evidence remains inconclusive. Oral histories can be distorted. But Collins isn’t relying on one line of proof. He combines biblical prophecy, ancient testimony, migration records, tribal customs, linguistic roots, and archaeological clues to construct a mosaic. Even if parts are wrong, the picture as a whole feels too coherent to dismiss outright.

If he’s right, then the story of the Lost Tribes didn’t end in exile. It morphed into empire, scattered through the mountains of Asia, resurfaced in the armies that toppled Rome, and shaped the nations that would one day dominate the West. The “lost” weren’t erased — they were renamed, reabsorbed, and retranslated into history.

This also has implications for how we read the Bible. If the tribes of Israel still exist — not just spiritually, but literally — then the prophecies about their roles in the “latter days” are not metaphors. They’re geopolitical. That challenges modern Christian assumptions and opens the door to a radically different view of history.

Maybe that’s why the idea remains taboo. It disrupts clean categories. It blurs the line between secular history and sacred narrative. And it suggests that the bloodline of ancient Israel may not have vanished into myth but may instead run quietly through the veins of millions today — unrecognized, unnamed, and still moving.

History didn’t forget the Ten Tribes. It just stopped looking in the right places.

Continued in the premium section…