The Making of Cyrus the Great

What made Cyrus unforgettable wasn’t how he conquered nations but how he conquered himself first.

The Making of Cyrus the Great

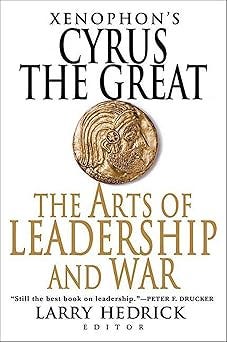

Alexander the Great slept with two books under his pillow: Homer’s Iliad and Xenophon’s Cyropaedia.

One was myth. The other was a manual.

The Cyropaedia is no ordinary biography. It’s part political philosophy, part leadership playbook, and part coming-of-age epic written by a soldier who studied under Socrates and fought alongside Sparta. Xenophon didn’t just write history. He imagined how a just king could be raised, tested, and forged.

That king was Cyrus the Great. But this isn’t a tale of conquest. Not yet.

It begins with a boy. Raised not with wealth, but with rules. Trained not to command, but to obey. Sent from the mountains of Persia into the jeweled court of Media, where his discipline would collide with luxury and his character would begin to shape empires.

The Persian Boy Who Refused to Be Ordinary

Cyrus the Great wasn’t born into power. He was born into training. In Persia, children weren’t taught with lullabies and games. They were raised in the public square under a system designed to form character. Boys learned justice by judging disputes. They learned self-restraint by waiting until permission was given to eat. They drank water from the stream, ate bread and cress, and trained with the bow and javelin. They didn’t learn what was easy. They learned what mattered.

From age sixteen, Persian youth slept outside, guarding the city at night and serving by day. They were taught to endure hunger, ignore fatigue, and obey their superiors. It wasn’t cruelty. It was citizenship. Their virtue was their armor.

Cyrus didn’t just survive this system. He excelled in it. But his story begins when he’s sent to live with his grandfather, the king of Media. That’s when the contrast between power and principle becomes impossible to ignore.

The Court That Couldn’t Corrupt Him

The Median court was dazzling. Painted faces. Perfumed robes. Jewelry and gold. Cyrus saw it all and didn’t flinch.

Instead of being seduced, he made fun of it. When offered dozens of dishes, he joked that Persians had a shorter road to satisfaction: meat and bread. He laughed at the idea that a feast should require an army of servants. Even the court’s traditions like the butler tasting the wine became material for his humor. But the deeper truth was this: Cyrus saw clearly what others had stopped questioning.

He didn’t just resist luxury; he responded with generosity. When he was given extravagant food, he gave it away to those who had taught or helped him. One dish to the horse trainer. One to the servant who honored his mother. One to the man who taught him to throw the javelin. Leadership, even then, was built on relationships.

People noticed. Not because he demanded attention. But because he gave it. The boy everyone expected to be spoiled became the boy everyone trusted.

Discipline in the Saddle, Daring in the Field

Cyrus became obsessed with learning to ride. Horses were rare in Persia, so he had no natural advantage. He fell. He got up. He fell again. And he laughed. He refused to only excel at what came easy. He wanted to master what humbled him.

Soon, he outpaced the other boys. The king’s private hunting grounds couldn’t satisfy him anymore. He wanted real danger—wild stags, charging boars, terrain that could kill. When denied permission, he didn’t throw a tantrum. He went quiet. Not out of pride, but out of longing. The fire in him had grown.

When the king finally allowed a hunt, Cyrus rode hard. He took risks. He failed, recovered, and succeeded. But his joy wasn’t in the kill, it was in sharing the prize. He wanted others to feel what he had felt: the beauty of effort and the dignity of danger.

Later, when Assyrian raiders struck the border, Cyrus joined the fight. For the first time, he wore armor. It fit not just his body, but his soul. He charged into battle with the cavalry. And when it was over, he didn’t boast. He studied the faces of the dead. Something had shifted. He was no longer a boy pretending to be a warrior. He was becoming one.

A Return Home, and a Different Kind of Battle

When it was time to leave Media, Cyrus gave away everything, the cloak off his back, the gifts from the king, the tokens of luxury. His friends returned them to the court. Cyrus begged they be allowed to keep them. He said he wanted to return to Media one day with his head held high, not his hands full.

Back in Persia, the other boys waited to see if time at court had made him soft. But he ate the same food, trained harder than ever, and never claimed privilege. He gave away his share of the feasts. He shared praise. He absorbed blame. They stopped mocking him. They started following him.

Cyrus was no longer just respected, he was trusted. He didn’t lecture. He didn’t posture. He simply showed up, again and again, and did more than was asked.

Then the Assyrian threat returned. And Cyrus was chosen to lead. Not by bloodline. But by character.

The Speech That Launched an Army

Cyrus didn’t pick generals from the elite. He chose 200 men he knew. Men who had trained with him. Each of them chose four more. Each of those raised thirty more from the commons. He built a chain of trust, not a ladder of hierarchy.

Then he stood before them and spoke.

He didn’t promise loot. He didn’t promise fame. Cyrus spoke of labor. Of sacrifice. Of discipline. Of how all their years of hardship had prepared them for one moment to prove that virtue wasn’t a fantasy.

He warned them: many men train their whole lives and never fight. Others die with their best still locked inside them. He said they would not be those men.

He reminded them that their enemies weren’t weak. They were undisciplined. Trained in show, not substance. Persia’s strength wasn’t its weapons. It was its soul. The habit of rising before dawn, of eating last, of enduring pain without complaint.

The men listened. Not because he shouted. But because he had lived what he preached.

The Rivalry at the Heart of Power

As Cyrus’s reputation grew, so did resentment. And it came from within his own camp. Cyaxares, his uncle and nominal king of Media, began to feel eclipsed by the young Persian whose courage, discipline, and charisma had made him the true leader of the army.

Cyrus had never publicly challenged Cyaxares. In fact, he had always shown respect. But victories on the battlefield, praise from the troops, and loyalty from conquered allies slowly made Cyrus the center of gravity. The soldiers followed Cyaxares by law, but they followed Cyrus by choice.

Tensions boiled over when foreign allies began offering their allegiance not to the king of Media, but to Cyrus directly. Cyaxares accused him of undermining royal authority. It was a test not just of loyalty but of character. Cyrus could have seized control outright. He had the army, the victories, and the favor of the people. But he didn’t.

Instead, he sent Cyaxares back his share of the spoils. He reaffirmed that his command was granted by the king. He insisted that his success served the Median crown. And it worked not because it flattered Cyaxares, but because it defused a crisis without breaking the chain of command.

This moment reveals something crucial: Cyrus didn’t lead through domination. He led through diplomacy, emotional intelligence, and restraint. He knew when to charge and when to yield.

It was this ability not just to win battles but to win people that would soon make him a king in more than name.

Character That Could Rule the World

Cyrus didn’t conquer the world by sword alone. He conquered it by clarity.

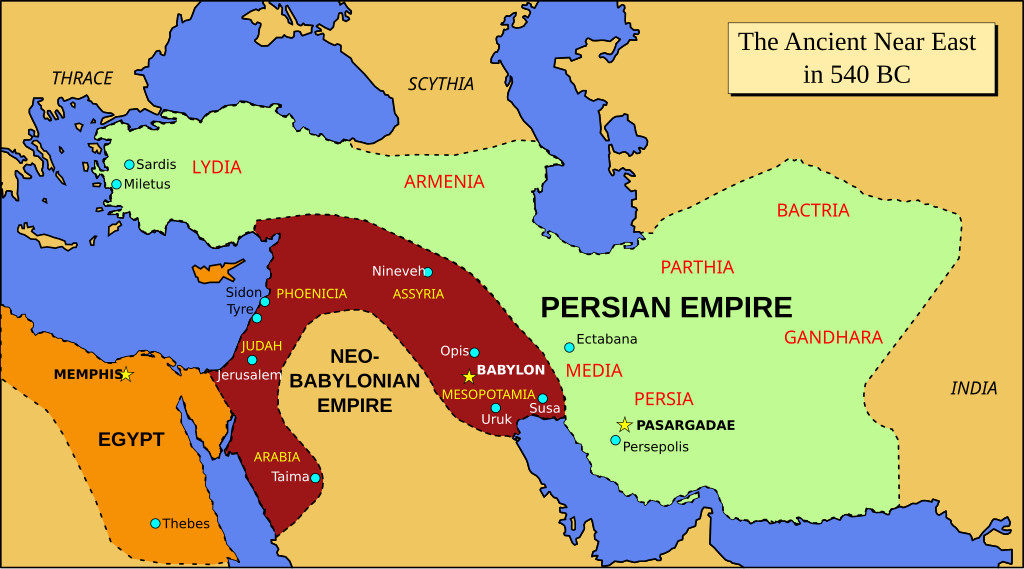

His empire stretched across languages, religions, and borders but he ruled through justice, not fear. People who never met him obeyed his laws. Why? Because his reputation arrived before his voice.

He didn’t flatten cultures. He preserved them. He didn’t punish difference. He understood it. He ruled like a man who had once sat with boys, drank from streams, and slept in the cold.

That’s why Xenophon admired him not because he was the most brilliant tactician, but because he was the most imitated. And that’s why Alexander the Great studied him. Because Cyrus showed that kingship is a weight, not a prize.

The Cyropaedia isn’t a manual. It’s a mirror. It asks one question: What if we raised boys to serve before they ruled?

Cyrus didn’t start as a legend. He started as a learner.

What made him great wasn’t victory. It was virtue. And in that, he remains timeless.

Art - Submission of Astyages by Maximilien de Haese

Book Corner

Continue reading in the premium section he Lost Story Behind Ezra and the Architecture of Persepolis…