Why Beauty Matters?

When we strip the world of beauty, we don’t just lose art—we lose hope, memory, and the quiet belief that life can be more than survival.

Picture a child growing up in a housing project made of grey concrete blocks, surrounded by littered lots, strip malls, and flickering screens. No gardens. No music in public spaces. No color on the walls. What message does that environment send about life? About dignity? We’ve built entire societies where the absence of beauty is considered normal. And slowly, that absence is eroding something vital in us. Because beauty isn’t a luxury. It’s a human need.

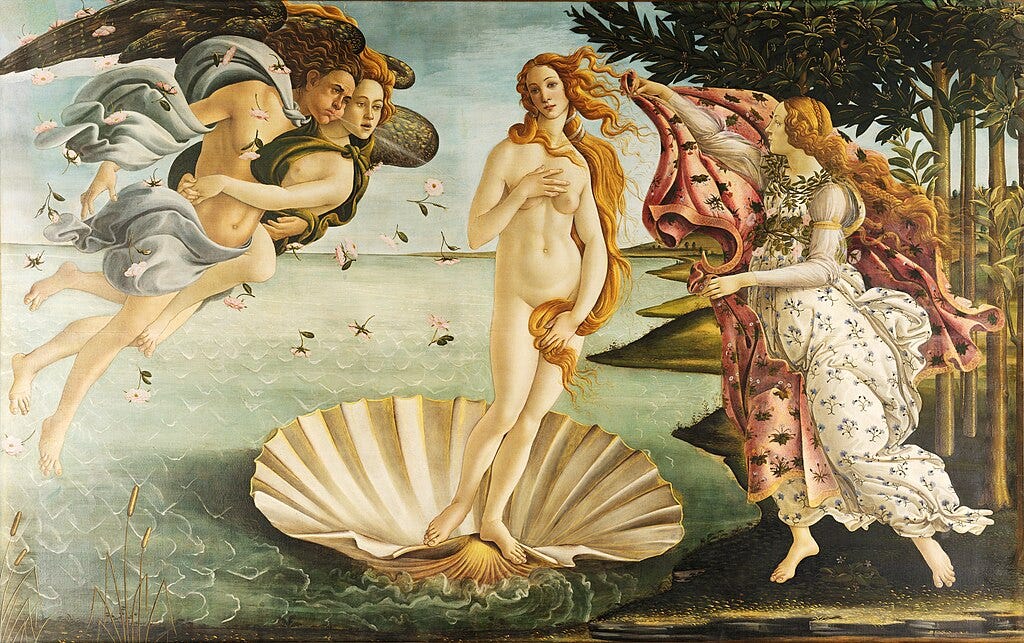

Western culture once believed that beauty had a place at the center of life. The Greeks saw it as an essential part of education. Plato argued that beauty was a gateway to truth. In his "Symposium," he wrote that contemplating beautiful things could lead the soul toward the divine. This wasn’t abstract. Statues like the Doryphoros by Polykleitos weren’t just for decoration, they were moral educators, showing ideal proportion, harmony, and self-mastery. Today, we dismiss that idea as outdated. But perhaps it’s our loss.

When people are surrounded by ugliness, by poorly built schools, decaying infrastructure, and soulless architecture, it doesn’t just affect their mood. It shapes their expectations of life. A study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology found that students perform better and report higher well-being in architecturally beautiful schools.1 Another from the University of Warwick showed that exposure to beautiful environments reduces stress and boosts productivity. Beauty literally changes how we function.2

Take the city of Florence. It isn’t just a tourist destination. It’s a living argument for why beauty matters. The Duomo, the Uffizi, even the street layouts reflect centuries of belief that the city should elevate the human spirit. Compare that to many modern urban centers, where efficiency has replaced imagination. Instead of awe, we experience alienation. Instead of wonder, weariness.

This shift isn’t accidental. The 20th century, with its obsession for functionality and mass production, turned beauty into a suspect idea. Le Corbusier called houses “machines for living.” Bauhaus stripped form to pure utility. Ornament was seen as crime. But we now live with the consequences: cities filled with brutalist architecture, public housing projects that depress rather than inspire, and schools that look like detention centers.