Why Roman Art Isn’t Just Greek Art in a Toga

Roman art carved every wrinkle, scar, and hollowed eye not to glorify beauty but to scream "I lived, I mattered, and I will not be forgotten."

The ancient Romans didn’t obsess over originality. They cared about what worked—what moved people, what endured, what commanded respect. That mindset gave us some of the most iconic art and architecture in history. In today’s edition, we take you to Rome.

In today’s free article, we break down why Roman art wasn’t just a copy, it was a transformation. A new language of power, practicality, and permanence.

In the premium section, we go deeper: why Rome isn’t just a city to visit, but the city to visit if you want to understand Western civilization—and delve into its architecture, stories, and the places that bring its legacy to life.

Why Roman Art Isn’t Just Greek Art in a Toga?

They say the Greeks gave the world beauty, but the Romans gave it identity. That single shift rewired the meaning of art across the Western world.

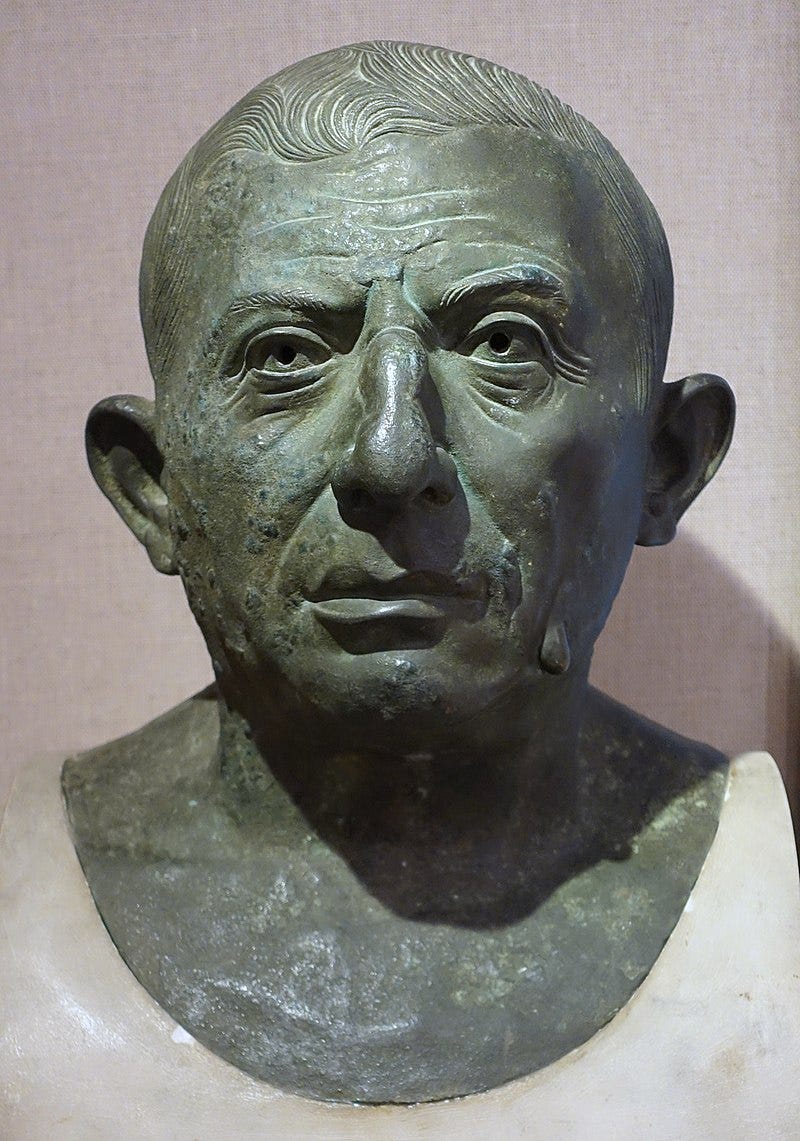

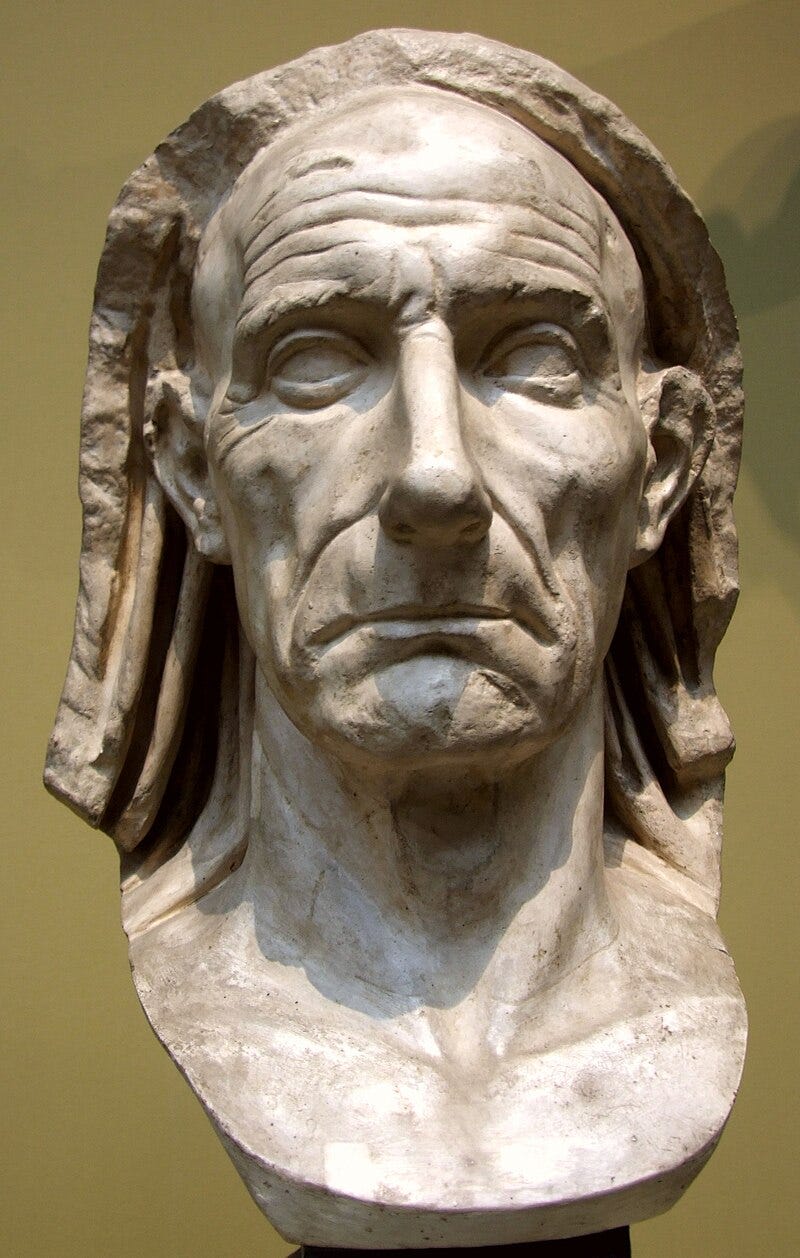

Walk into a museum and find a Roman bust, creases deep across the forehead, eyes set with tired intensity, cheeks collapsing inward. It looks almost too real. Not divine. Not idealized. Just true. And in that truth lies the heart of Roman art.

For years, historians told a lazy story: Rome copied Greece. Rome had no originality. Rome borrowed the style but missed the spirit. But Christopher Hallett1, in his sharp and essential essay “Defining Roman Art,” says that view misses what matters most. Roman art wasn’t about imitation, it was about intention.

Where Greek art aimed for perfection, Rome celebrated experience. Age wasn’t something to smooth over, it was something to etch deeper. Those furrows and lines weren’t flaws. They were a résumé.

This style of extreme realism—what scholars call verism—was a moral code carved in stone. It said: “I served. I aged. I earned this face.” Romans didn’t just want to be remembered. They wanted to be remembered right.

The more you study Roman art, the clearer the contrast becomes. Greeks sculpted the divine into the human. Romans did the reverse. They took the mess and mortality of human life and sculpted it into civic myth.

And here’s the kicker: most of the artists weren’t even Roman. They were Greek slaves and freedmen working in Rome, trained in older traditions. But the art they made served Roman values. Greek technique. Roman message.

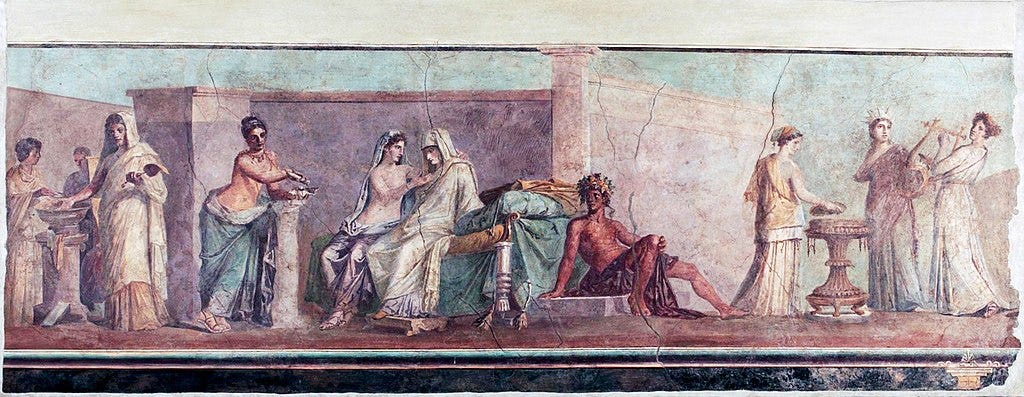

That’s what makes Roman art powerful. It doesn’t just replicate style, it retools it. Every bust, sarcophagus, and wall painting had a job. To commemorate. To convince. To console. It was art as rhetoric.

Take funerary monuments. They weren’t elegies. They were arguments. Carved inscriptions shouting a legacy. Sculpted faces carrying forward the virtues of discipline, duty, and descent. These were not vague tributes. They were identity manuals.

Even when Romans borrowed mythological scenes, they often twisted them. Hercules wasn’t just a demigod; he was a model of labor and endurance. Art didn’t just entertain. It instructed.

Politics bled into all of it. Augustus commissioned portraits that rewrote the face of power, softened, youthful, god-kissed. A calculated pivot from the Republican era’s wrinkled realism. But still Roman in its propaganda instinct.

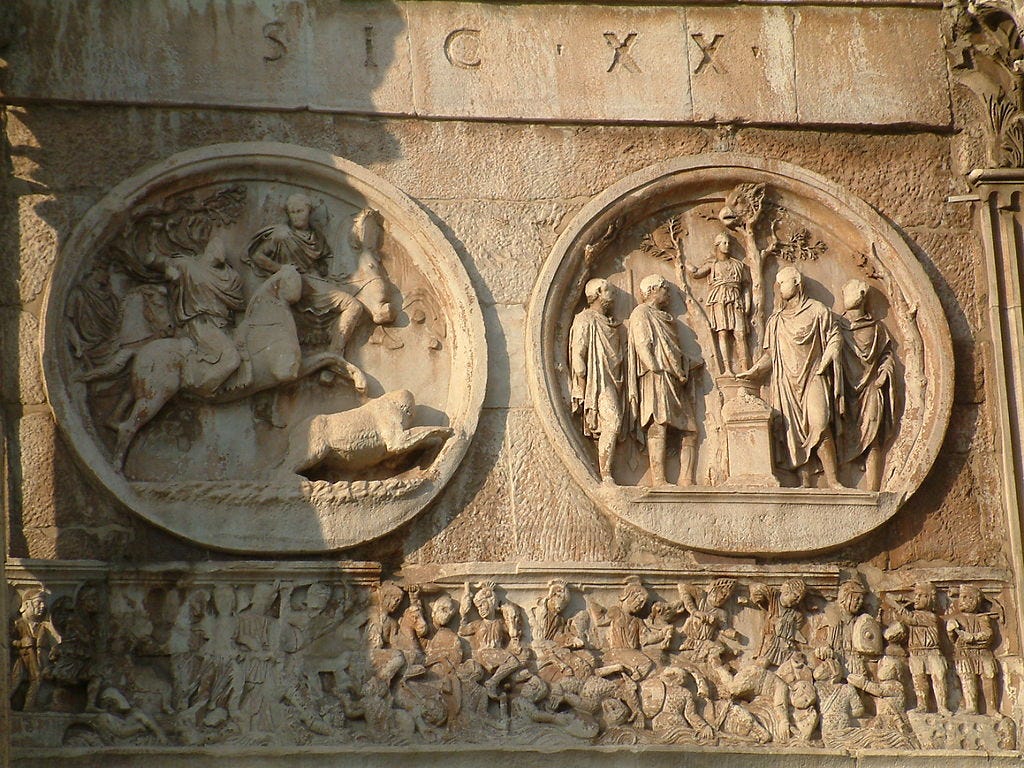

Public monuments told stories, too—arches that boasted conquest, columns that mapped campaigns, altars that mixed religion and rule. These weren’t decorations. They were state media, etched in marble.

Roman architecture took it even further. Greek buildings sought proportion. Romans engineered impact. Arches, vaults, concrete—tools of civic awe. Temples didn’t just reach the heavens. They organized the city.

So how do we define Roman art? Hallett’s answer isn’t about form. It’s about function. Roman art is what it does. It builds memory. It asserts power. It defines who belongs. That definition rewrites the narrative. Rome wasn’t creatively bankrupt. It was pragmatically brilliant. It understood that art doesn’t need to be original, it needs to work.

And work it did. Roman visual culture outlasted the empire. Medieval churches, Renaissance politics, neoclassical states all drew from its language. Why? Because it fused beauty with use.

What’s wild is how relevant that feels now. We live in a world obsessed with filters, with curating appearances. Roman art says: Show the wrinkles. Show the life you’ve lived. That’s the real legacy.

Hallett’s greatest insight is that Roman art wasn’t a style, it was a conversation. With the past. With the viewer. With time itself. It didn’t aim to flatter. It aimed to last.

And maybe that’s the lesson. Greece gave us ideals. Rome gave us selves. And art, ever since, has lived in the tension between the two.